Way to Be Weird, Earth: 10 Strange Findings About Our Planet in 2018

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hooray for weird!

Earth has been around for about 4.5 billion years, and in that time, the planet has undergone some dramatic changes. These include the formation and breakup of supercontinents, the appearance and disappearance of oceans, extreme ice ages that nearly blanketed the globe with ice, and multiple mass extinctions that wiped out as much as 96 percent of all life at the time.

Compared with its volatile younger self, the Earth of today seems pretty tame. But our world is also a dynamic planet, and there is much about its history and ongoing processes — on land, in the oceans and deep under the surface — that scientists are still discovering. Here are just a few examples of times during the past year when new findings about oddball Earth threw us for a loop.

Split continent

On March 19, a gaping chasm yawned in Kenya's Great Rift Valley, following heavy rains and seismic activity. The rift measured several miles long and was over 50 feet (15 meters) wide, and it represents shifts that are currently taking place deep below Earth's surface, in crustal plates under Africa.

Africa sits atop two plates: Most of the continent rests on the Nubian plate, but part of eastern Africa lies on the Somali plate. Tectonic shifts, driven by the active mantle, are pulling the plates apart, which can open rifts in the surface. However, it will take tens of millions of years for the continent to separate into two pieces. [Read more about the Kenya rift]

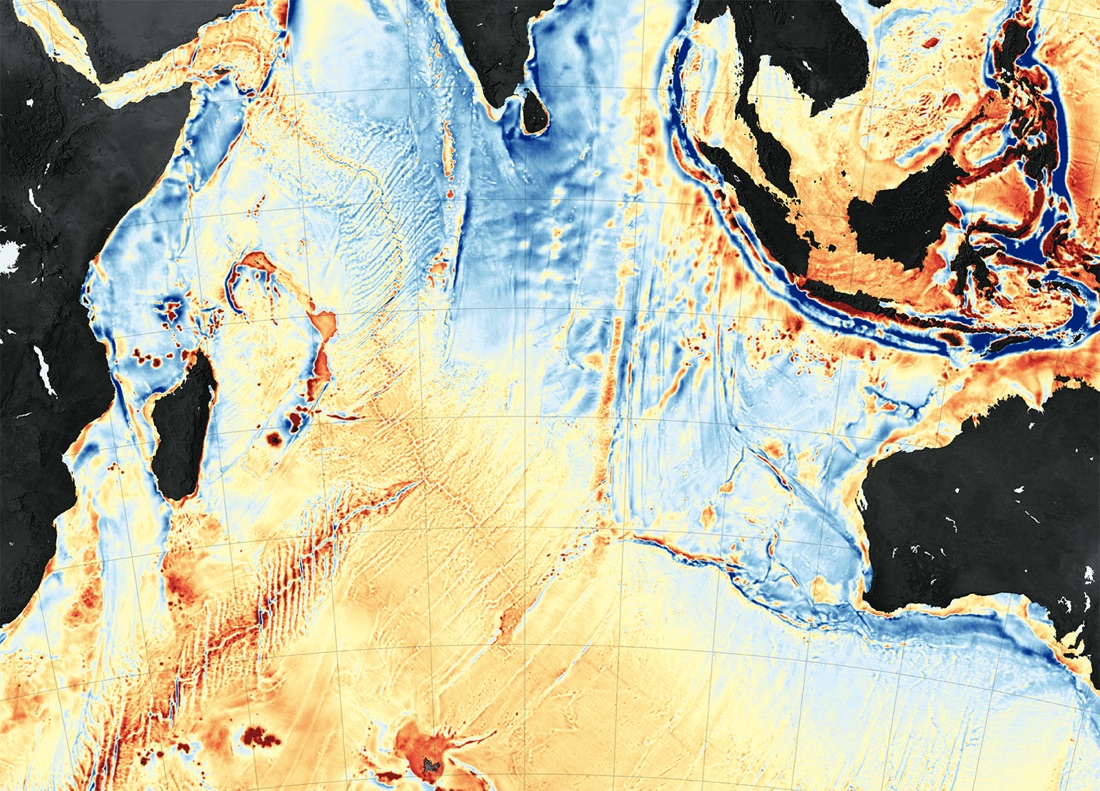

Sinking seafloor

As Earth warms, melting glaciers and ice sheets pour water into the oceans, raising sea levels around the world. At the same time, the weight of all that extra water is pushing down the sea bottom. Researchers recently investigated how melted ice flowing from land may have affected the shape of the ocean floor between 1993 and the end of 2014.

They discovered that global ocean basins deformed an average of 0.004 inches (0.1 millimeter) per year, with a total deformation of 0.08 inches (2 mm) over two decades. As satellite measurements of changes in sea level don't account for a lower ocean bottom, these findings suggest that prior studies' data could be underestimating sea level rise by approximately 8 percent, the scientists reported. [Read more about the sinking ocean bottom]

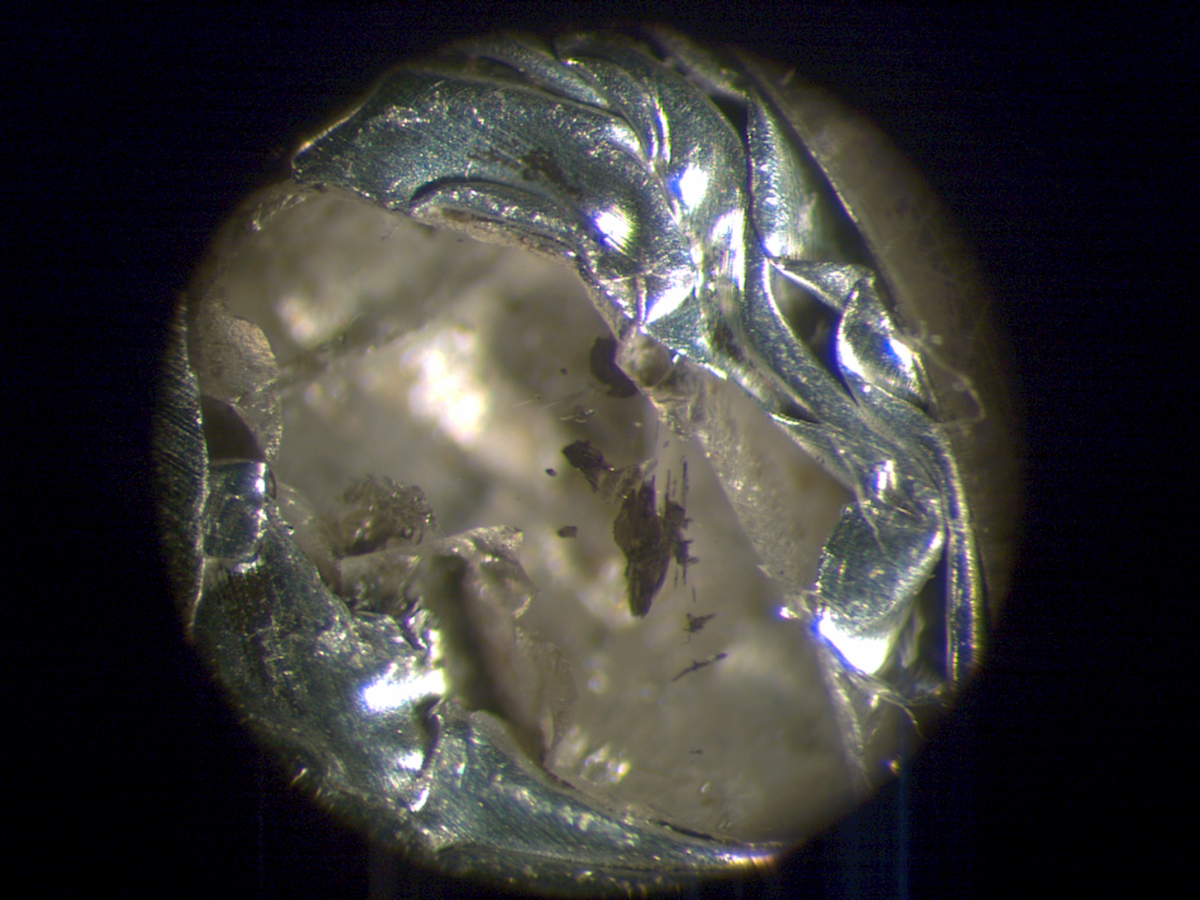

Mystery mineral

A mineral that had never been seen before in nature recently emerged in a tiny diamond excavated in South Africa's Cullinan mine. Though measuring only 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) in length, the diamond holds a wealth of information for geologists about this rare mineral, known as calcium silicate perovskite (CaSiO3).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though rare on Earth's surface, CaSiO3 is thought to be common deep underground and is perhaps the fourth most common mineral in Earth's interior. But it is unstable and therefore is exceptionally hard to locate above ground. The newfound diamond likely originated at a depth of about 435 miles (700 kilometers), and its robust structure protected and preserved the mineral, which was visible to the naked eye inside its diamond home. [Read more about the mystery mineral]

Continent chunk

Rock comparisons from two distant continents revealed that a wayward piece of North America is currently stuck to Australia. Sedimentary stones in the Georgetown region of northern Queensland were unlike other rocks in Australia but were strikingly similar to rocks found in Canada today.

Researchers suggested that 1.7 billion years ago, a portion of what is now North America separated and drifted south, colliding with northern Australia about 100 million years later. The violence of the collision likely raised mountain ranges in the region, much as the Himalayas were formed about 55 million years ago, after the collision of Asian and Indian continental plates. [Read more about the wayward rock]

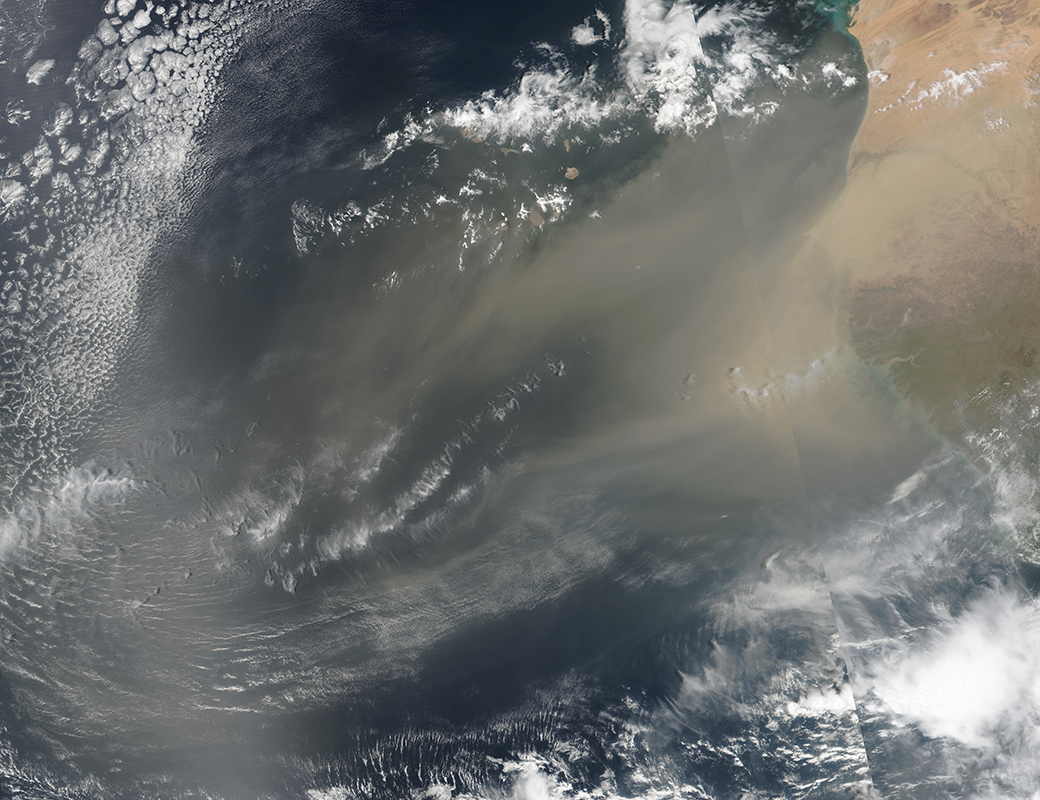

Virus rain

Billions of viruses ride air currents around the planet, sometimes traveling thousands of miles, and are raining down on Earth's surface. Borne on winds at heights of 8,200 to 9,840 feet (2,500 to 3,000 m) above sea level, viruses hitchhike on sea-spray vapor and tiny soil particles; scientists discovered that, in just one day, 11 square feet (1 square m) of ground could be showered with hundreds of millions of viruses (and tens of millions of bacteria).

After analyzing "microbe highways" in air currents, researchers found that viruses were up to 461 times more abundant than bacteria, because the viruses attached to lighter particles and could thereby stay aloft longer and travel farther. [Read more about the viruses raining down on us]

Ocean-eater

Movement among Earth's tectonic plates is hijacking water from the oceans and pushing it into the planet's interior. Researchers eavesdropped on seismic mutterings at the Mariana Trench, where the Pacific plate slides under the Philippine plate — called a subduction zone. The velocity of subsurface rumbles hinted at the amount of water that gets carried along for the ride as the rocks scrape along one another.

Measurements of water temperature and pressure — along with the speed of the seismic hiccups — revealed that subduction zones likely siphon 3 billion teragrams (a teragram is a billion kilograms) of water every million years. That's about three times the amount that was previously estimated. [Read more about how Earth eats its own oceans]

Bottoms up

Tornadoes have long been thought to take shape from the top down, forming from swirling air currents during powerful storms. But new research turns that idea upside down, literally, suggesting that tornadoes gain their twist from the ground up.

Scientists investigated four tornadoes that formed from supercell storms between 2011 and 2013, finding that all of them formed funnel shapes on the ground before extending upward into the clouds. For one tornado, which struck El Reno, Oklahoma, on May 24, 2011, observers on the ground captured a photo of the twister touching the Earth several minutes before radar spotted the tornado above the ground, at a height of about 50 to 100 feet (15 to 30 m).

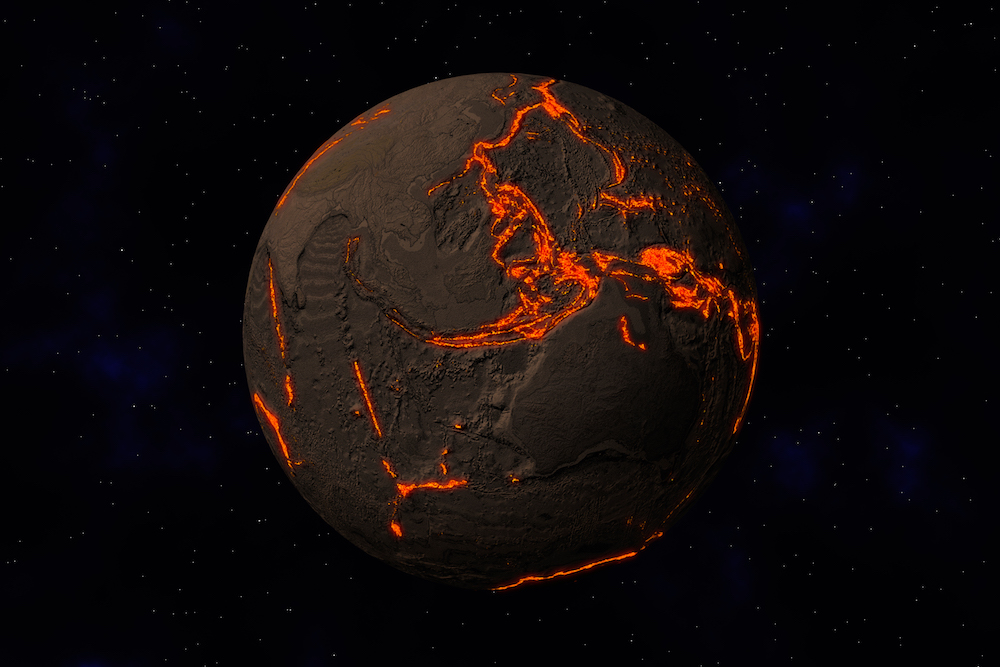

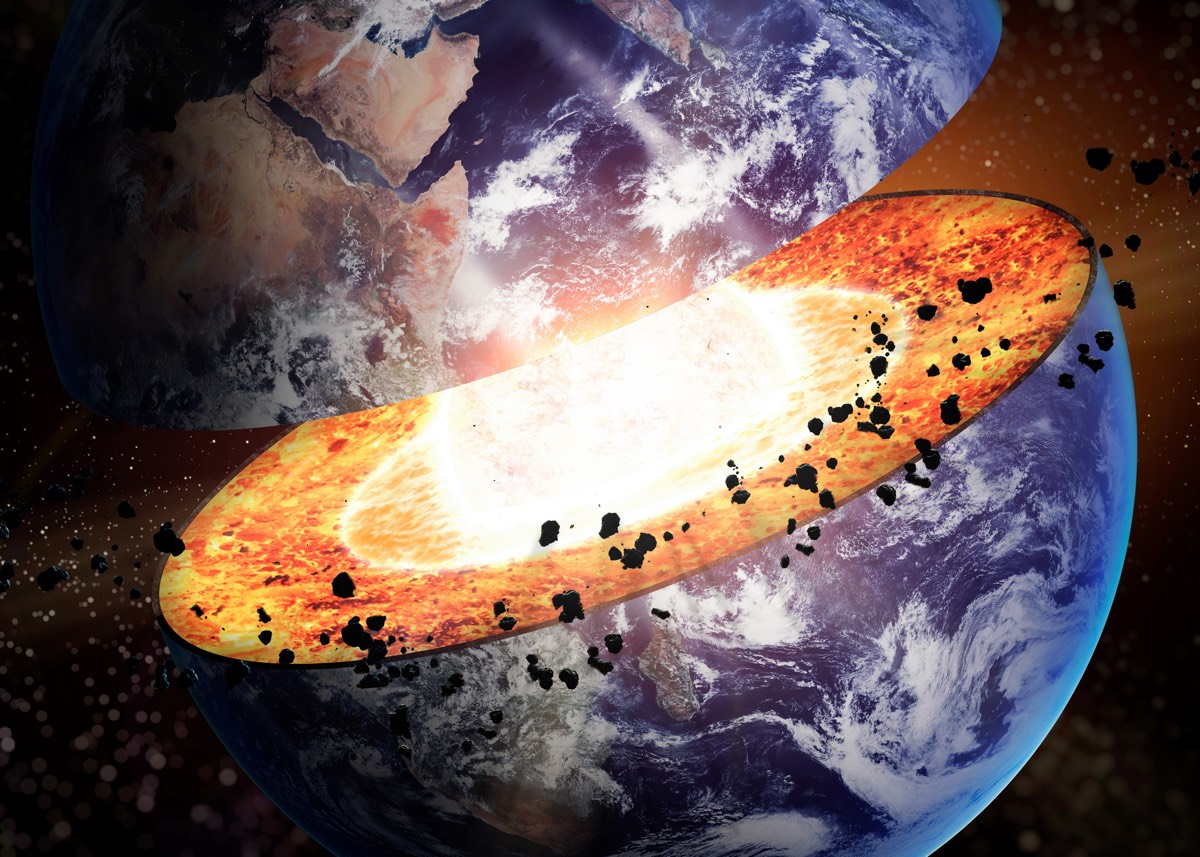

Magma sea

Deep in Earth's mantle lie mysterious blobs that may be remnants of an ancient magma ocean that dates to 4.5 billion years ago and that formed after the cosmic collision that created the moon. These blobby pools close to the planet's core are called ultra-low-velocity zones, because seismic waves traveling through the planet's interior slow significantly when they cross these regions.

But what are these "blobs?" Lab experiments suggested they may consist of an iron-oxide-rich mineral called magnesiowüstite, from a magma ocean created after a large object from space struck Earth billions of years ago. As the ocean lost the heat generated by the impact, this mineral crystallized and produced pockets of iron oxide, which sank to the base of the mantle to form the blobs that remain today. [Read more about the strange blobs]

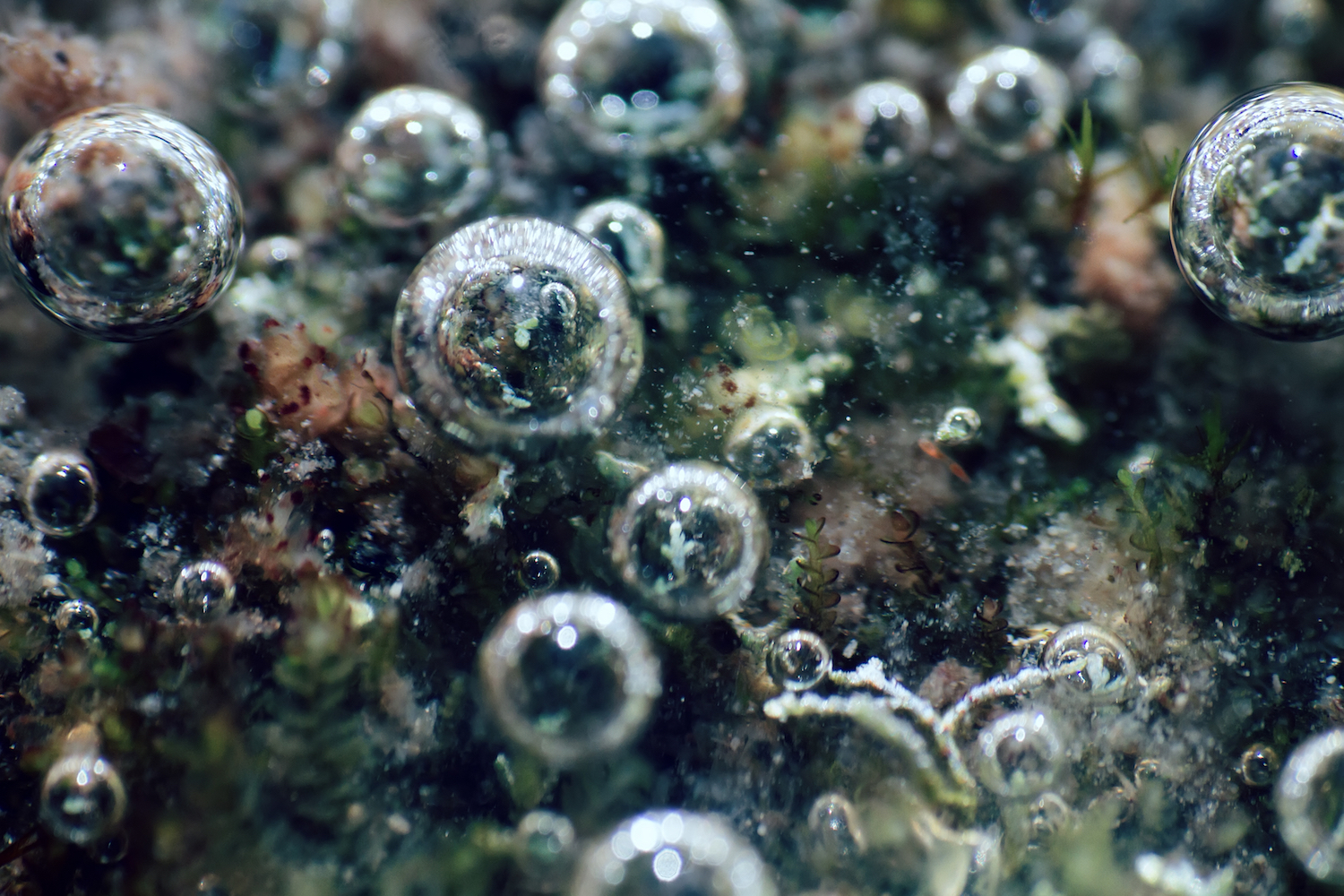

Plant sounds

Can you hear the sound of plants "breathing?" You can if you listen carefully to red algae underwater. As the algae carry out photosynthesis — processing carbon dioxide and sunlight, as plants do on land — they produce tiny bubbles that collect on their surfaces. When the bubbles detach to rise to the water's surface, they make a "ping" sound, researchers recently discovered.

Scientists first detected the sounds in waters around coral reefs near Hawaii. While the noise was initially attributed to snapping shrimp, the researchers soon realized there was a correlation between the sound and the presence of algae. Reefs can suffocate if they are covered by too much algae, and eavesdropping on "pinging" algae communities could provide early warnings for runaway algae growth that could endanger vulnerable reefs. [Read more about these photosynthesis pings]

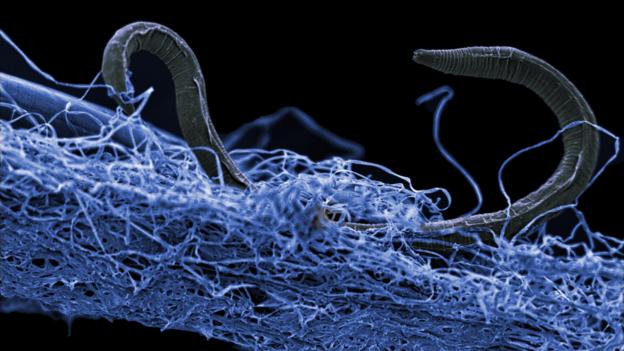

Deep biosphere

Over the past decade, scientists have discovered diverse and numerous microbial communities living far below Earth's surface, in an environment known as the deep biosphere. Researchers recently revealed that this region could be home to millions of unknown species — and the organisms have been evolving there since the Earth was young.

In fact, the deep biosphere's estimated carbon biomass — carbon belonging to living organisms — may be nearly 300 to 400 times that of all the people on the planet. As the intriguing species that survive and thrive below Earth's surface come to light, they also provide insights that may inform the search for microscopic life on other worlds, scientists recently reported. [Read more about life thriving in Earth's deep biosphere]

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus