This Tiny Diamond Contains a Mineral That's Never Been Seen Before

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A schist in the hand may be quite continental, but diamonds are a geologist's best friend.

For proof, look no further than a recently mined diamond that contained a mineral that had never been seen in nature — until now.

The discovered mineral — called calcium silicate perovskite (CaSiO3)— was found trapped inside a diamond excavated from South Africa's Cullinan mine (most famous for yielding the world's largest diamond in 1905, part of which now adorns the crown jewels of the United Kingdom). The finding, published online today (March 7) in the journal Nature, provides an important clue to the puzzle of how Earth's inner structure behaves. [Shine On: Photos of Dazzling Mineral Specimens]

While rare to human eyes, calcium silicate perovskite may be shockingly ordinary deep inside the Earth — in fact, it's thought to be the fourth most abundant mineral inside the planet, especially prevalent in slabs of oceanic crust that have plunged into the planet's mantle at tectonic boundaries.

Despite the mineral's theorized prevalence, however, previous studies have never yielded observable evidence of its existence. It's thought to occur deep inside Earth's mantle, however — some 700 kilometers (435 miles) below the planet's surface, the researchers said.

"Nobody has ever managed to keep this mineral stable at the Earth's surface," study co-author Graham Pearson, a professor in the University of Alberta's Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, said in a statement. "The only possible way of preserving this mineral at the Earth's surface is when it's trapped in an unyielding container like a diamond."

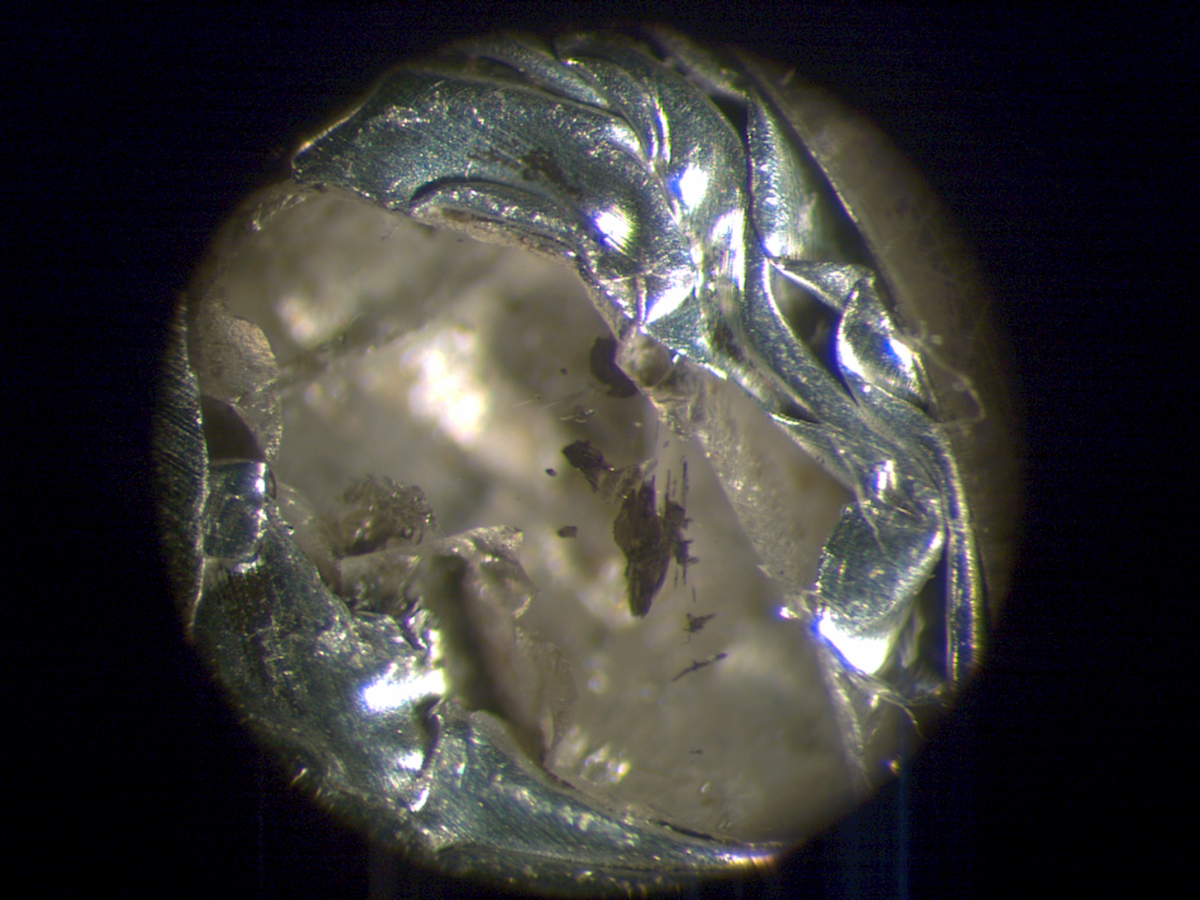

In the new study, Pearson and his colleagues analyzed a tiny diamond (roughly 3 millimeters across) excavated from Cullinan less than 1 km (0.6 miles) below the Earth's surface. Despite this relatively shallow depth, the researchers determined that the crystal was an example of a "deep diamond" that most likely had been formed about 700 km below the Earth's surface, derived from a subducted slab of ocean crust and exposed to some 240,000 atmospheres of pressure.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The chunk of calcium silicate perovskite within the gemstone was visible with the naked eye after the diamond was polished, the researchers wrote, but proper analysis and imaging required an international effort. X-ray and spectroscopy tests confirmed that the diamond did contain calcium silicate perovskite — quite possibly the first intact sample ever seen.

"Diamonds are really unique ways of seeing what's in the Earth," Pearson said. "And the specific composition of the perovskite inclusion in this particular diamond very clearly indicates the recycling of oceanic crust into Earth's lower mantle. It provides fundamental proof of what happens to the fate of oceanic plates as they descend into the depths of the Earth."

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus