Your 'Fat-Toothed' Relative May Not Make It for Thanksgiving. He Vanished from Earth 300 Million Years Ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

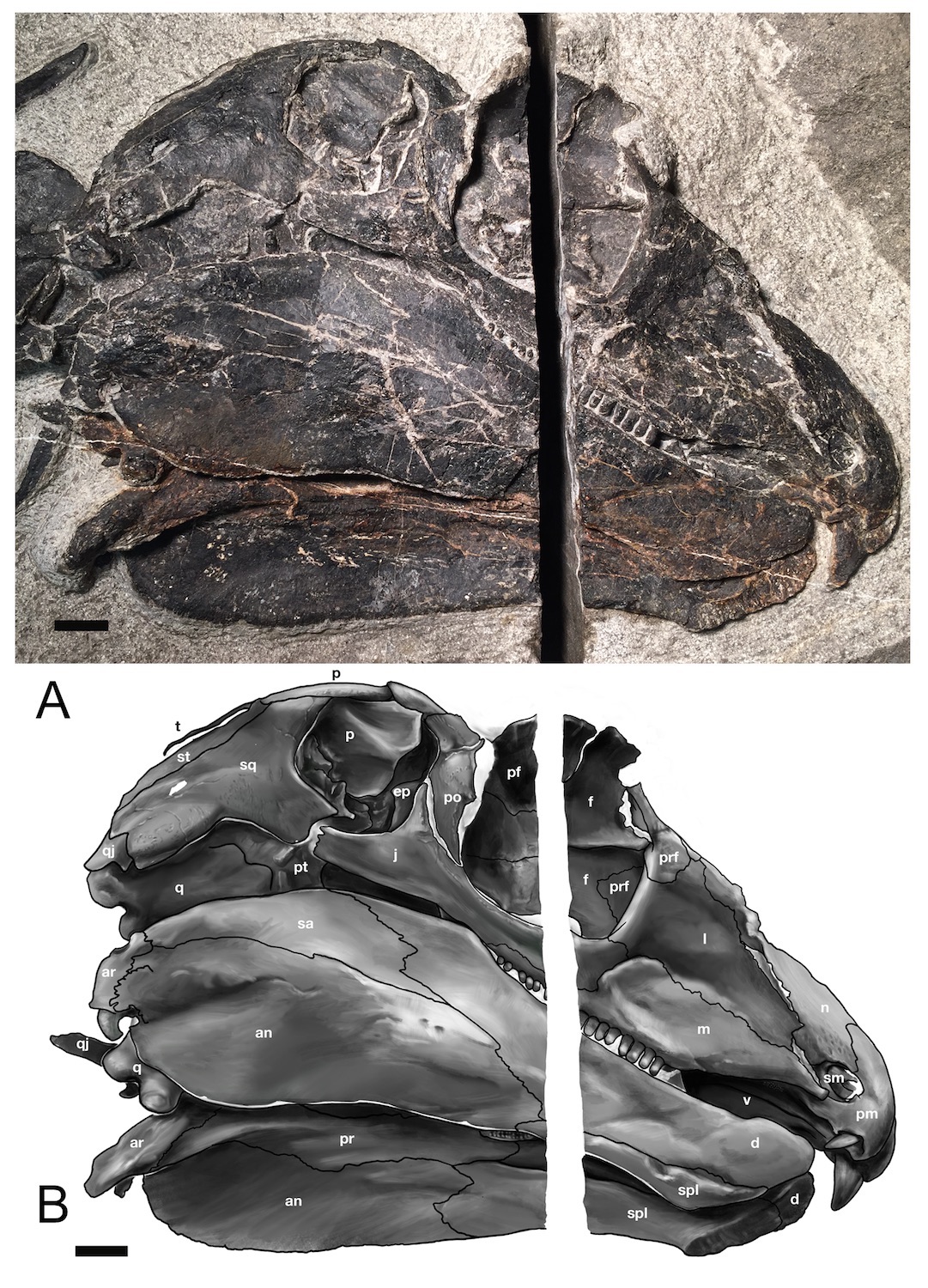

Although it may look like a dinosaur, a newly identified sail-backed reptile that lived 300 million years ago is actually more closely related to humans, a new study finds.

The bizarre 5-foot-long (1.5 meters) reptile is a sail-backed eupelycosaur (yoo-PEL-ee-ko-sore), a group of animals "that were very successful during the Permian," a period that lasted from about 300 million to 251 million years ago, just before the dawn of the dinosaurs, said study lead researcher Spencer Lucas, a curator of paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque.

"Eupelycosaurs include the ancestors of mammals, making this new skeleton more closely related to us than to dinosaurs," Lucas told Live Science in an email. [Photos: Unearthing Dinosauromorphs, the Ancestors of Dinosaurs]

A University of Oklahoma geology class discovered the newfound eupelycosaur fossils peeking out of a roadcut in New Mexico in March 2013. They told Lucas, who then collected the "exquisitely preserved but incomplete skeleton" with his colleagues in 2013 and 2014, he said.

After marveling at the reptile's well-preserved, 17-inch-tall (43 centimeters) back sail, the researchers couldn't stop ogling its robust teeth. While the beast has a number of small teeth inside its mouth, it sports larger chompers at the tip of its snout, inspiring the scientific name Gordodon kraineri. The genus name is taken from "gordo," the Spanish word for "fat," and "odon," the Greek word for "tooth." Gordo is also a reference to Alamogordo, the nearby city in southern New Mexico where the fossil was found. The species name honors Karl Krainer, a geologist at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, for his contributions to discoveries about the late Paleozoic geology and paleontology of New Mexico.

The approximately 75-lb. (34 kilograms) reptile had surprisingly advanced structures in its skull, jaws and teeth, indicating that it was a selective feeder that dined on high-nutrient plants, Lucas said.

"Other early herbivorous reptiles were not selective, chomping on any plants they came across," Lucas said. "But Gordodon had some of the same specializations found in modern animals, like goats and deer."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Until now, the oldest animals on record with teeth that were as specialized as G. kraineri were found in rocks no older than 205 million years ago, dating to the late Triassic period. "Gordodon extends this advanced type of plant eating by 95 million years," Lucas said.

In effect, the discovery of this "fat toothed" reptile rewrites paleontologists’ understanding of the early history of reptilian herbivory, he said.

The reason for G. kraineri's distinctive sail, however, is still a mystery.

"It has long been thought that the sails on the backs of reptiles like Gordodon were used in thermoregulation — the animal pumped blood into the sail, which increased the surface area over which the blood flowed, so that the blood could be more rapidly heated or cooled," Lucas said. "But, this is not certain."

The study was published online in the November issue of the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

- Photos: Thousands of Dinosaur Tracks Along Yukon River

- Photos: Duck-Billed Dinos Found in Alaska

- Photos: Early Dinosaur Cousin Looked Like a Croc

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus