'Ravenous, Hairy Ogre' Microbe May Represent Entirely New Branch on the Tree of Life

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Who needs aliens when there are bizarre life forms still to be discovered in Canada?

Scientists recently detected two previously unknown species of microbes in a Canadian dirt sample, and the specimens were so unusual that the researchers had to reorganize the tree of life to make room for them.

The microbes, also known as protists, belong to a group with the tongue-twisting name hemimastigotes, and the first-ever genetic analysis of these peculiar microorganisms revealed that they were even stranger than anyone suspected. [Magnificent Microphotography: 50 Tiny Wonders]

Hemimastigotes, first observed in the 1800s, were previously classified as a phylum within a much larger group known as a super-kingdom, though it was unclear where exactly they belonged.

But new DNA evidence showed that they deviated dramatically from all other forms of life in that super-kingdom. In fact, hemimastigotes may represent an entirely new super-kingdom unto themselves, demanding a brand-new branch on the tree of life, scientists reported in a new study.

Named for a monster

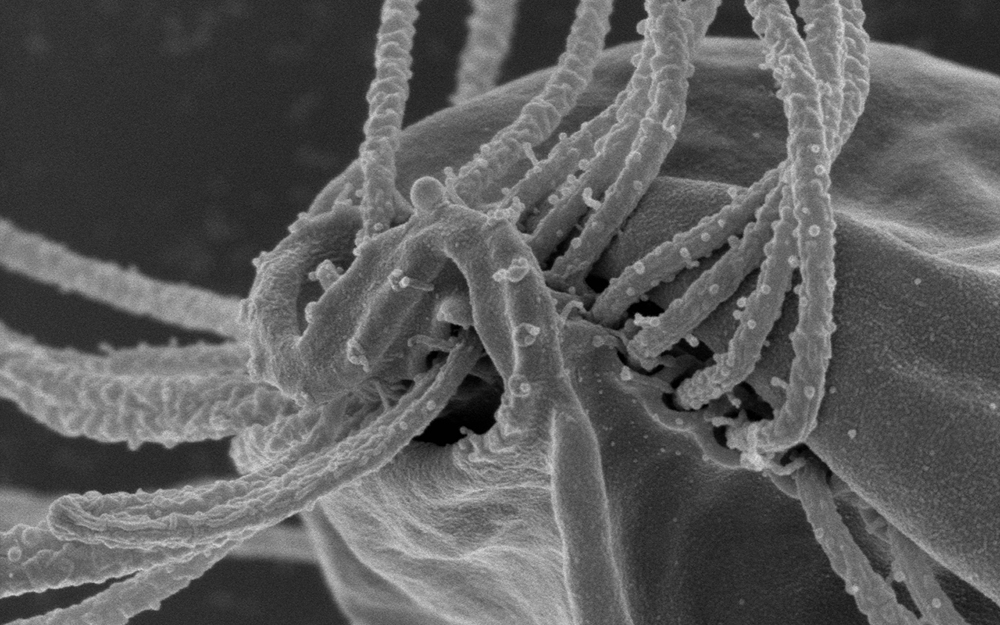

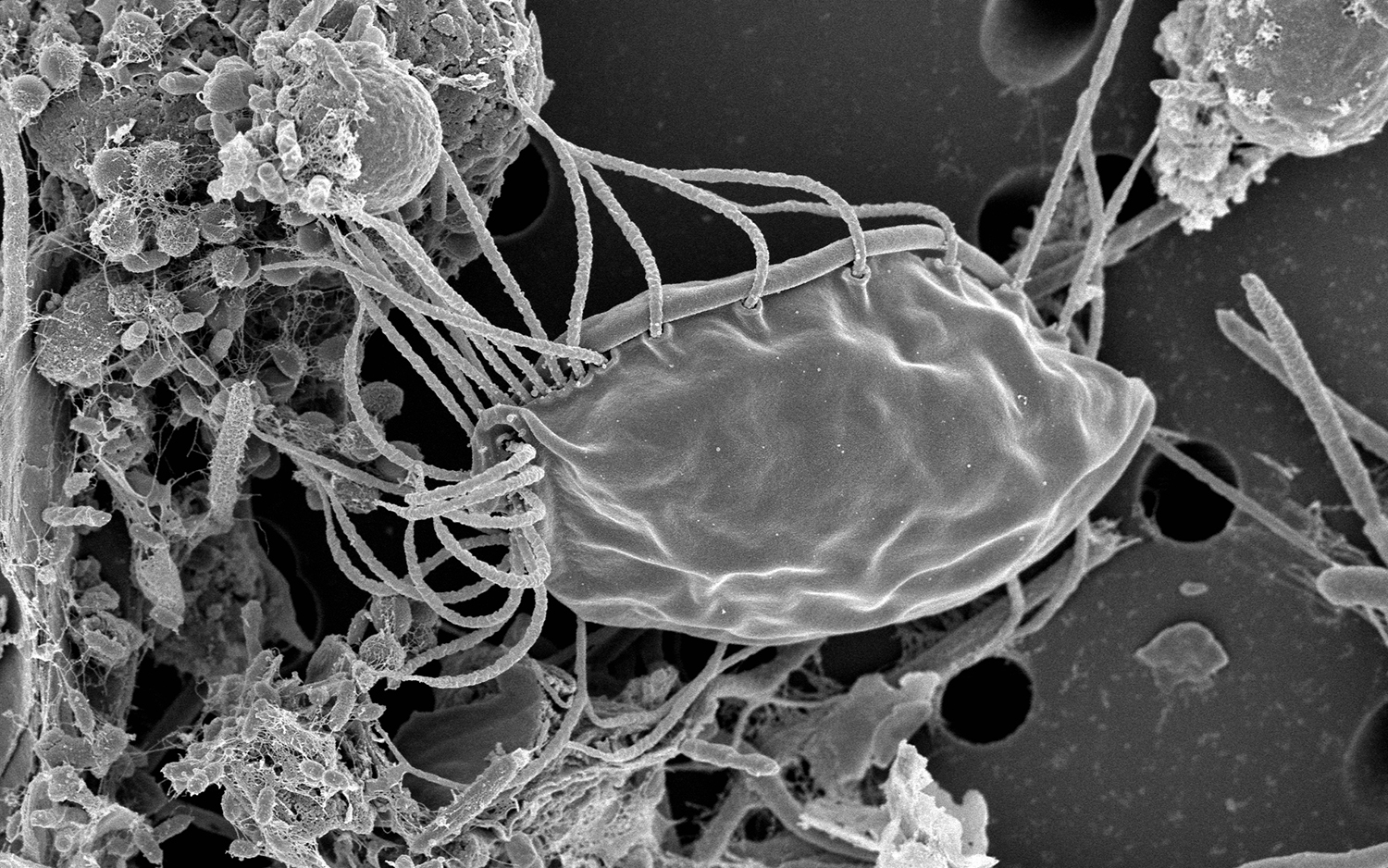

Like other hemimastigotes, the newfound species has an oblong body surrounded by rows of threadlike flagella; under the 3D magnification of scanning electron microscopy, the creatures somewhat resemble hairy pumpkin seeds.

"They tend to scuttle around somewhat awkwardly — superficially, they look like ciliates (another major group of 'hairy-looking' cells) but swim in a less coordinated manner," study co-author Yana Eglit, a doctoral candidate in biology at Dalhousie University in Canada, told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Eglit collected the oddball organisms while she was hiking along a trail in Nova Scotia; whenever she and her colleagues are outdoors, they are almost always on the lookout for still-undiscovered microbes in a range of habitats — "from beach sands to lakes to soil at our feet," Eglit told Live Science.

"Of course, if we see some unusual puddle or salt lake or whatever, we can sample those too. We're opportunists that way," Eglit said.

Nova Scotia is a territory of the Mi'kmaq First Nation, so the scientists gave one of the new microbes a name inspired by a creature in Mi'kmaq folklore. "Kukwes" is described by the Mi'kmaq people as "a ravenous, hairy ogre," and the newfound microbe, now known as Hemimastix kukwesjijk, is a voracious predator that reminded the scientists of the hirsute ogre, according to the study.

Using a technique known as single-cell transcriptomics, the scientists looked into individual cells in the microbes. They observed the activity of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, as they ferried information between hundreds of genes.

Previous evaluations of hemimastigotes classified them by the size and shape of their visible structures. By sequencing this genetic information, the scientists were able to categorize hemimastigotes with unprecedented accuracy, unveiling a lineage that holds a unique position among other eukaryotes — organisms with a membrane-wrapped nucleus.

"It's a branch of the 'Tree of Life' that has been separate for a very long time, perhaps more than a billion years, and we had no information on it whatsoever," lead study author Alastair Simpson, a biology professor at Dalhousie University, said in a statement.

The study's findings highlight hemimastigotes' previously unrecognized importance for interpreting the evolution of complex cellular life — from piecing together the origins of cell infrastructure to resolving relationships between Earth's very first organisms, the study authors reported.

"This discovery literally redraws our branch of the 'Tree of Life' at one of its deepest points," Simpson said. "It opens a new door to understanding the evolution of complex cells — and their ancient origins — back well before animals and plants emerged on Earth."

The findings were published online Nov. 14 in the journal Nature.

- Microbe Masterpieces: Scientists Create Cool Art from Bacteria

- Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures

- Code of Life: 10 Animal Genomes Deciphered

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus