Bizarre 'Headless Chicken Monster' Drifts Through Antarctic Deep

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

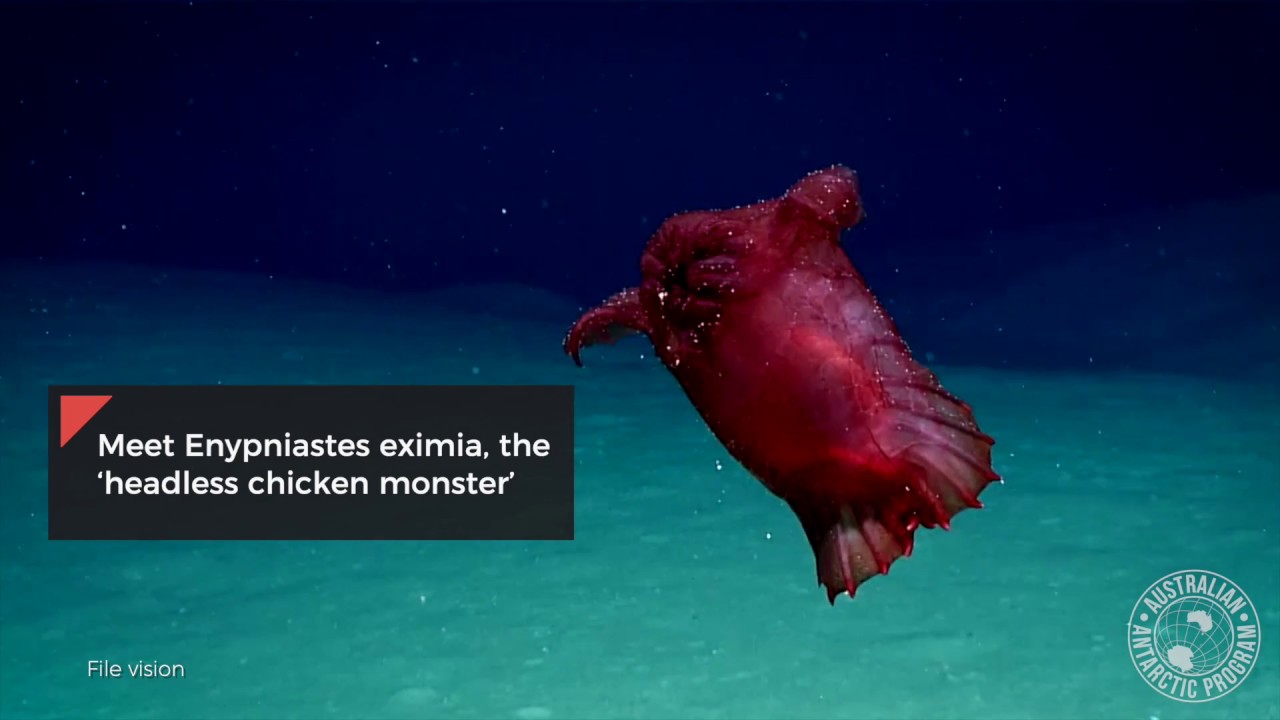

Meet the real-life "chicken of the sea": a strange, pinkish-red creature with a body like a plump-breasted and decapitated chicken, earning the creature the name "headless chicken monster."

In truth, it is neither a chicken nor a monster. It's the swimming sea cucumber Enypniastes eximia, and scientists recently captured video of this bizarre, hen-mimicking swimmer in the Southern Ocean near eastern Antarctica, where it has never been seen before.

Footage shows the colorful sea cucumber drifting through the water; fins at the top and bottom of its tubby, translucent body almost resemble the stubby wings and legs on plucked, pink poultry ready for the pot. If you squint, you might think you're looking at the result of an ill-fated tryst between a chicken and Aquaman. [In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures]

Not everyone recognizes the gelatinous sea cucumber's similarity to a chicken, though its appearance is undeniably peculiar. Photos of the crimson creature that were shared around the Live Science newsroom prompted comparisons to "a frilly pillow case," "a bloody flying squirrel," "a raw steak with fins" and "what you'd get if you asked a machine learning algorithm to make you a picture of a fish." [Editor's note: All of these are wrong; it looks like a floating chicken head.]

The so-called headless chicken monster, previously found only in the Gulf of Mexico, was recently detected by scientists with the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD), part of the Australian Department of the Environment dedicated to investigating Antarctica and the Southern Ocean. The researchers used new camera technology to detect the swimming sea cucumber at a depth of about 9,800 feet (3 kilometers) below sea level, AAD representatives said in a statement.

On average, E. eximia measures between 2 and 8 inches (6 to 20 centimeters) in length; adults' colors can range from dark reddish brown to crimson, though juveniles are typically a paler shade of pink, according to a study published in 1990 in the journal Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences.

While most types of sea cucumbers spend the majority of their time on the sea bed, swimming sea cucumbers like E. eximia land only to feed, researchers reported in the 1990 study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cameras designed for the AAD expedition were deployed on fishing lines, according to a YouTube video the agency shared yesterday (Oct. 21). The equipment is durable enough to be tossed over the side of a boat and can operate reliably for extended periods of time in the total darkness and crushing pressures of the deep ocean, AAD program director Dirk Welsford said in the statement.

"Some of the footage we are getting back from the cameras is breathtaking, including species we have never seen in this part of the world," Welsford said.

In addition to offering glimpses of unusual marine life such asE. eximia, the new camera system reveals the complex interplay of life in Southern Ocean depths, Welsford said. It will help scientists to advise policy makers about conserving vulnerable ecosystems that are threatened by commercial fishing, Welsford explained.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus