This Tick's Worst Day Ever Frozen in Time for 100 Million Years

Imagine your worst day ever, preserved for eternity. That's what happened to a very unlucky tick 100 million years ago.

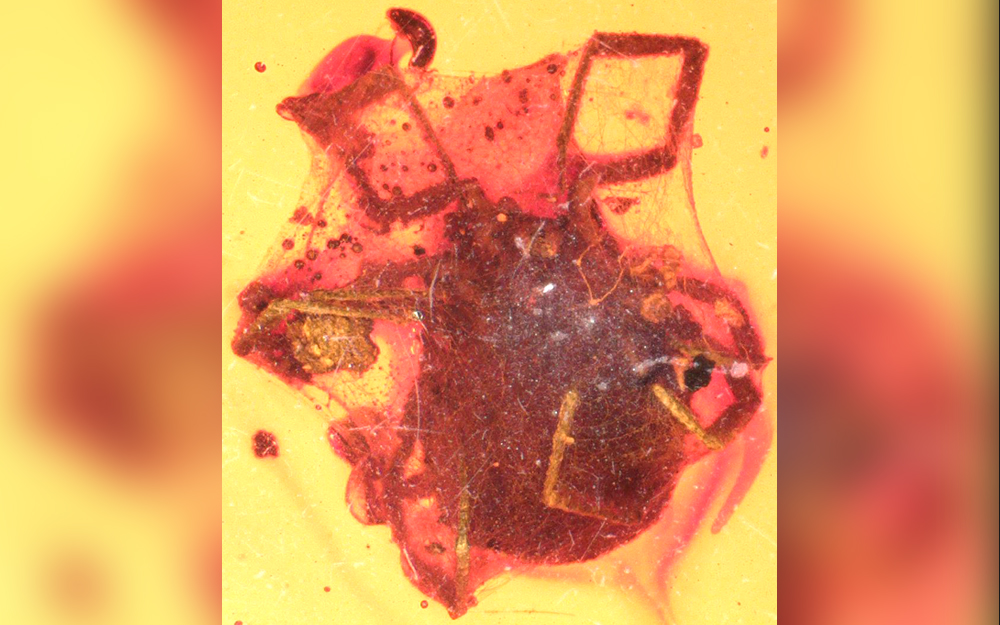

First, the hapless arthropod stumbled into a spider's web. The spider scurried over, swaddling the struggling tick in layers of confining silk. As if that weren't bad enough, things suddenly took a turn for the (even) worse. Sticky sap dripped onto the tick, sealing it in an airtight blob that eventually hardened into an amber tomb. And that's where the tick remained to this day, with all the unfortunate details of its last moments frozen in place and on display forever.

Though a terrible episode for the tick, this was a great discovery for scientists; it's the oldest example of a preserved tick in the fossil record and the only known fossil of a tick specimen that was caught by a spider, researchers reported in a new study. [In Photos: Amber Preserves Cretaceous Lizards]

Amber-trapped ticks are exceptionally rare. Hardened amber starts out as tacky tree resin, so the creatures that it ensnares tend to live in or around the bases of trees. Ticks, on the other hand, usually cling to grasses on the ground, where they can latch onto succulent hosts for a blood meal. But this particular tick took to the trees — and it was a decision that the creature would regret.

The researchers identified the tick as belonging to the family of "hard ticks" called Ixodidae. Like other hard ticks, this one had a tough shield on its back to keep from being squished by animals it latched onto.

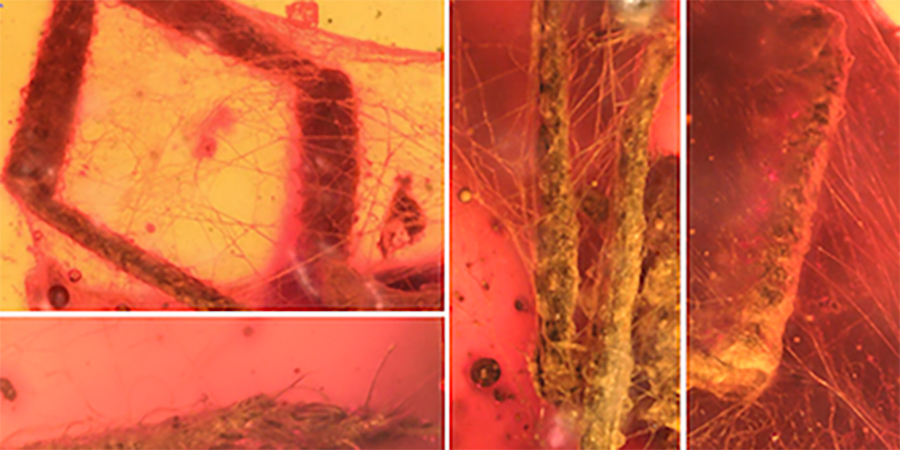

Inside the amber, the tick was swaddled in masses of filaments. Fungal growth can also produce delicate threads, but the branching pattern of the filaments and the absence of fungal droplets told the scientists that the strands were made of silk, likely unspooled by a spider.

But was the tick wrapped up to become the spider's dinner? Not necessarily; it's possible that the spider didn't even eat ticks, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some spiders alive today do eat ticks, but as the Cretaceous spider wasn't trapped in the amber alongside its captive, it's impossible to tell what species it was and whether it was a tick-eater.

Another possibility is that the spider spun its silk net to immobilize the tick so it wouldn't wreck the carefully constructed web, the study authors reported.

Suspended in time, this moment from millions of years ago delivered the worst possible outcome for the tick. But it also offers a fascinating snapshot of the life-and-death struggles of species in the distant past, said study co-author Paul Selden, a professor of geology at the University of Kansas.

"It's really just an interesting little story — a piece of frozen behavior and an interaction between two organisms," he said in a statement.

The findings were published online June 13 in the journal Cretaceous Research.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus