Lyme Disease Soars in Michigan as Tick Populations Grow

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Cases of Lyme disease in Michigan have risen dramatically in recent years, and a new study links that trend to larger and more widespread tick populations.

Researchers collected data from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services on 1,057 Lyme disease cases diagnosed between 2000 and 2014, and aligned them with a new analysis of tick distribution across the state. Results showed that not only did the number of yearly infections in the state increase significantly over the 15-year period, but so did the number of counties where ticks had been seen, or found to be established.

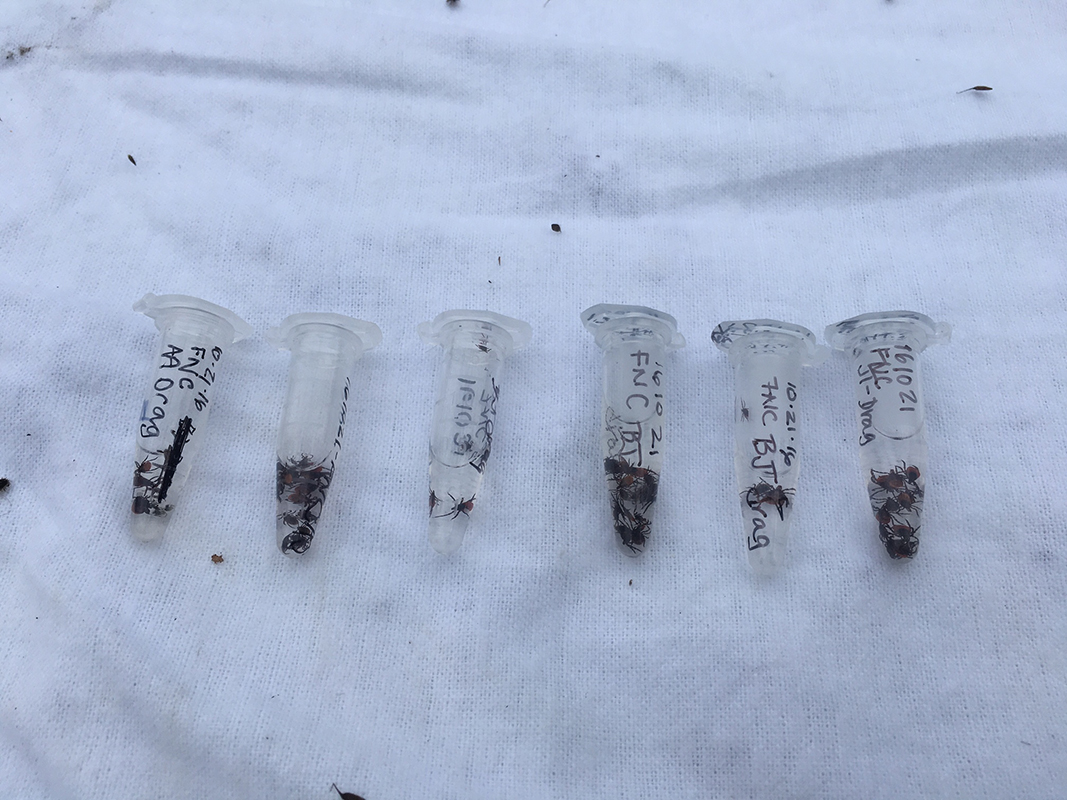

And the number of infected people may be much higher than the records indicate, the researchers said. Because Lyme disease is frequently misdiagnosed as other illnesses, reported cases likely represent only a fraction of true Lyme disease infections — perhaps as little as 10 percent, the study authors reported. [Bloodsuckers! Michigan Ticks and Larvae, in Photos]

Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, and can be transmitted to humans only through the bite of a tick carrying that bacterium. Black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis), also known as deer ticks, are the most common vectors for Lyme disease in the northeastern, north-central and mid-Atlantic United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Ticks are not born carrying Lyme, but instead contract the disease as larvae by feeding on infected animals, such as deer, robins or mice, study co-author Jean Tsao, an associate professor of fisheries and wildlife at Michigan State University, told Live Science in an email. The ticks retain the bacteria into adulthood, and once a tick becomes infected, it can pass the bacteria along to the next animal it bites.

"But when the mom converts her blood meal into eggs, she doesn't pass on the pathogen, so her eggs are 'clean,'" Tsao explained.

Lyme on the rise

Until recent decades, most cases of Lyme disease in the Midwest occurred in Wisconsin and Minnesota, the study authors reported. Black-legged tick populations were thought to be low across Michigan, with established populations linked to only one county in the state's Upper Peninsula, which is adjacent to Wisconsin.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, from 2000 to 2014, the number of new cases of Lyme disease in Michigan expanded, both numerically and geographically. Fewer than 30 cases were reported annually between 2000 and 2004, but that number climbed to 90 cases per year by 2009, and 166 Lyme disease cases were reported in 2013, according to the study.

At the same time, the number of counties where Lyme disease appeared also rose, with cases appearing not only in the in top of the Upper Peninsula, but also in the state's Lower Peninsula, along the Lake Michigan coast and in the southwestern part of the state.

More Lyme disease cases, and their widening range, suggested that tick distribution in Michigan was also growing, and Tsao and her colleagues set out to test that pattern, the researchers said. [Gross! Watch a Tick Bite in Action (Video)]

An uptick in ticks

A prior study from 1998 showed that black-legged ticks in Michigan were established in five counties. But by 2016, established populations were found in 24 counties, and 18 more showed evidence that black-legged ticks were living there. This expansion coordinated geographically with the spread of Lyme disease cases, the study authors reported.

The researchers don't think that the ticks migrated on their own — more likely is that the bugs hitchhiked on the animals that they bite, Tsao said. When ticks are abundant, enough of them could catch a ride to a place where ticks hadn't been seen before, and establish a new population, Tsao said.

Meanwhile, tick surveys conducted by the researchers also revealed that a substantial number of the insects were carrying Lyme-causing bacteria.

"At our 'hotspot' in southwest Michigan, typically about 20 to 25 percent of the nymphs are infected, and about 40 percent of the adults are infected," Tsao said.

Taking precautions

The spread of ticks and tick-borne diseases into new areas around the U.S. will likely continue — particularly for the black-legged tick, whose range has grown significantly over the past 20 years, said Rebecca Eisen, a research biologist with CDC's Division of Vector-Borne Diseases.

"Most of this expansion has been seen in the Upper Midwest and the Northeast. These regions also have an increased number of counties that are now considered high incidence for Lyme disease," Eisen told Live Science in an email.

"It is important for people to know that ticks are spreading to new areas and that there are steps they can take to prevent tick bites," she added.

Precautions include avoiding areas with high grasses and thick vegetation, using repellent containing 30 percent diethyltoluamide (DEET) on exposed skin, and treating clothing and camping gear with products that contain the insecticide permethrin, Eisen said. After coming indoors, showering as soon as possible is recommended to wash ticks away or detect them before they have a chance to bite. Any attached ticks should be removed as quickly as possible.

And if fever or body aches develop after a recent visit to an area that could be a tick habitat, the person should go to a health care provider, Eisen added.

The findings were published online Feb. 10 in the open-access journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus