Ticks May Help Detect Lyme-Disease Bacteria in People

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new potential test for persistent Lyme disease uses an organism that's known to be good at picking up diseases: ticks.

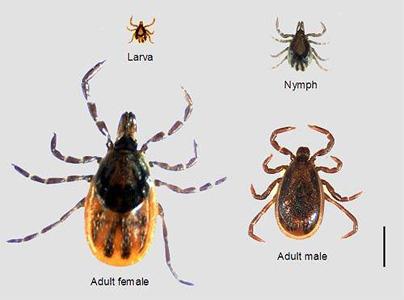

In a new study, disease-free ticks were allowed to feed on the skin of 25 people who'd had Lyme disease in the past and received antibiotic treatment for it, and on one person who was receiving antibiotic treatment at the time. Ten of the participants had what's known as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, a condition in which symptoms such as fatigue and muscle aches persist even after the patients complete antibiotic therapy.

One of the goals of the study was to see whether, through their blood-sucking abilities, the ticks were able to pick up the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, called Borrelia burgdorferi.

Currently, people with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome have no way of knowing for sure whether they still harbor this bacterium in their bodies. That's because current tests for Lyme disease can't determine definitively whether the bacterium has been eliminated. [Top 10 Mysterious Diseases]

"While most patients improve after taking antibiotics, some patients continue to have symptoms," the researchers said. While the cause of these persistent symptoms is not known, "one possibility is that the antibiotics have not successfully gotten rid of all of the bacteria," they said.

The method of using ticks to detect Borrelia burgdorferi is known as xenodiagnosis. While previous studies have used xenodiagnoses to detect Borrelia burgdorferi in animals, this is the first time the method has been tried in people, said study researcher Dr. Adriana Marques, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The primary goal of this early study was to look at the safety of xenodiagnoses in humans, and the results showed the method is safe and well tolerated in people. The most common side effect was a mild itching where the ticks attached, Marques said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of the 23 participants who had at least one tick available for testing, 19 tested negative for Borrelia burgdorferi. Two people had indeterminate results, and two had positive results.

However, the researchers need to do more studies to determine exactly what a positive result means. It's still not clear if a positive result represents live organisms in the body or the remnants of infection, the researchers said. (In the current study, the researchers could not definitively conclude that live bacteria were present in the bodies of the two individuals with the positive test results.)

The study results were published online Feb. 11 in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. The researchers are continuing to recruit participants for their ongoing study.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus