New Barrel-Shaped Structure Discovered Inside Sperm

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

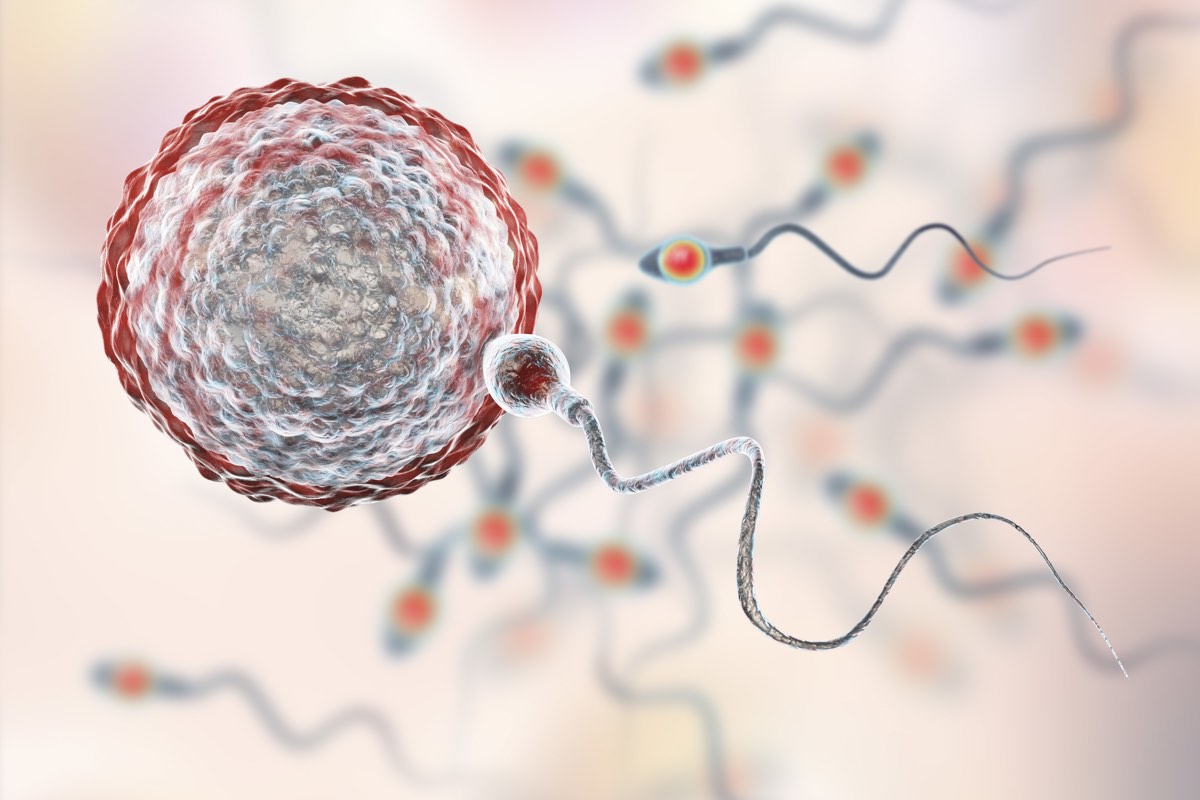

Human sperm cells are well-studied, so scientists were completely surprised to find a previously unknown structure in the little swimmers. And perhaps more surprising, this newfound structure may contribute to infertility, miscarriages and birth defects, the investigators said.

On the flip side, once scientists understand this structure better, it may help them develop new therapies for male infertility and learn more about early human embryonic development, the researchers said.

The newly identified part is a centriole, a barrel-shaped structure made of short microtubules. Researchers already knew that sperm cells contain one centriole, but the new discovery brings the total to two centrioles per sperm. [Sexy Swimmers: 7 Facts About Sperm]

However, the newfound centriole has a slightly different structure than the previously known one, so the researchers are calling it atypical in shape.

"This research is significant because abnormalities in the formation and function of the atypical centriole may be the root of infertility of unknown cause in couples who have no treatment options available to them," study researcher Tomer Avidor-Reiss, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Toledo in Ohio, said in a statement. "It also may have a role in early pregnancy loss and embryo development defects."

Previously, researchers thought that sperm carried just one centriole, which then duplicated itself if the sperm met an egg. That's because the egg does not have a centriole, while a zygote — or a fertilized egg — needs two centrioles to start the development of a fetus, the researchers said.

These centrioles play a pivotal role. They are needed for building the cell's cytoskeleton (the structure that maintains cell shape) and completing accurate cell division, the researchers noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By learning how centrioles work during the early stages of reproduction, scientists may be able to pinpoint if these structures are involved with any type of male infertility or later problems with the developing embryo.

"Since the mother's egg does not provide centrioles and the father's sperm possesses only one recognizable centriole, we wanted to know where the second centriole in zygotes comes from," Avidor-Reiss said. "We found the previously elusive centriole using cutting-edge techniques and microscopes. It was overlooked in the past, because it's completely different from the known centriole in terms of structure and protein composition."

This isn't the only recently uncovered structure in human sperm. Earlier this year, researchers announced the discovery of a mysterious spiral in the tail of human sperm; this structure may give the sperm a boost while it's swimming, Live Science previously reported.

The new study was published online June 7 in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus