Hundreds of Purple Octopus Moms Are Super Weird, and They're Doomed

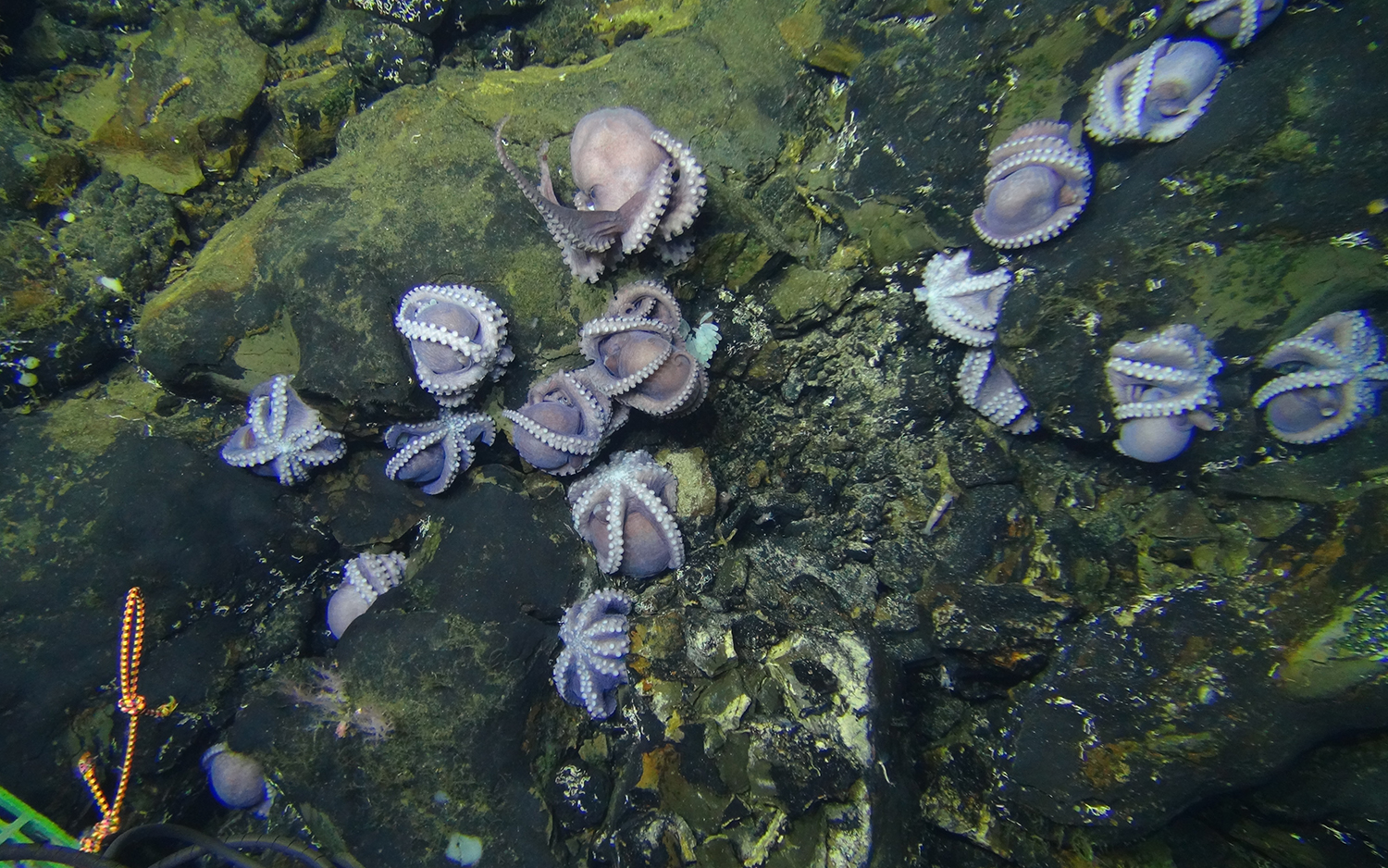

Miles beneath the ocean's surface, in the darkened waters along a rocky seafloor, a submersible vehicle unexpectedly encountered a bizarre spectacle: hundreds of small, purple octopuses, many of them mothers protecting clusters of eggs, clinging to the hardened lava from an undersea volcano.

The sight was astonishing, researchers said. During multiple dives, the submersible's cameras captured as many as 100 octopuses at a time, most clutching broods of eggs attached to the rocky outcrop, clustered around cracks in the cooled lava substrate.

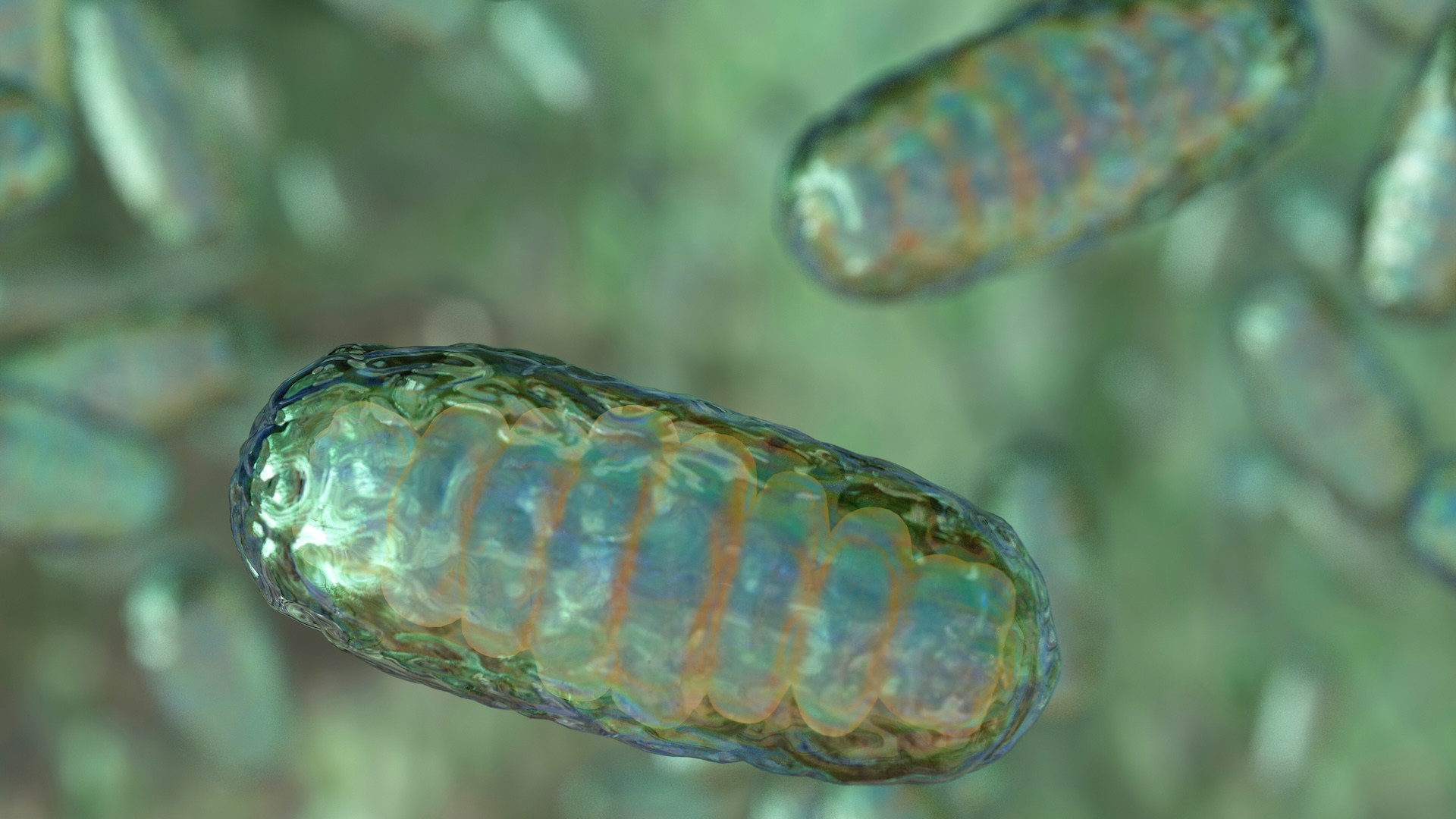

The octopuses, which sport enormous eyes in comparison to their dinner plate-size bodies, were identified as a new species in the genus Muuscoctopus. That made the sightings even stranger, as octopus in that group are usually loners that don't gather in dense communities. [8 Crazy Facts About Octopuses]

Things got weirder from there. Water temperatures where the colony huddled were much warmer than is suitable for deep-sea octopuses, which have trouble extracting oxygen from water that's too hot. In fact, researchers who investigated the colony found that none of the embryos were developing and reported in a new study that the adults were "unlikely to survive."

What's the story behind this mysterious, doomed gathering of octopus mothers, huddling uncomfortably in volcano-warmed waters and guarding eggs that will never hatch?

"They shouldn't be there"

"When I first saw the photos, I was like, 'No, they shouldn't be there! Not that deep and not that many of them,'" study co-author Janet Voight, an associate curator of zoology at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, said in a statement released by the museum.

The tale unfolded on the Dorado Outcrop, located about 155 miles (250 kilometers) west of Costa Rica at a depth of 9,842 feet (3,000 meters). Study co-author Geoff Wheat, a geochemistat the University of Alaska Fairbanks, led two expeditions to the outcrop — in 2013 and 2014 — recording photos and hundreds of hours of video of the unusual octopus gathering.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During the dives, the researchers collected data on water temperature and evaluated the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water. They also observed 606 octopuses (though some may have been counted multiple times, the researchers said). The animals' smooth skin, the two rows of suckers on their arms and their brooding postures identified them as members of the Muuscoctopus genus.

However, the scientists collected no individuals, and the newfound species remains undescribed, according to the study. [Octlantis: See Photos of Tight-Knit Gloomy Octopus Communities]

A recipe for disaster

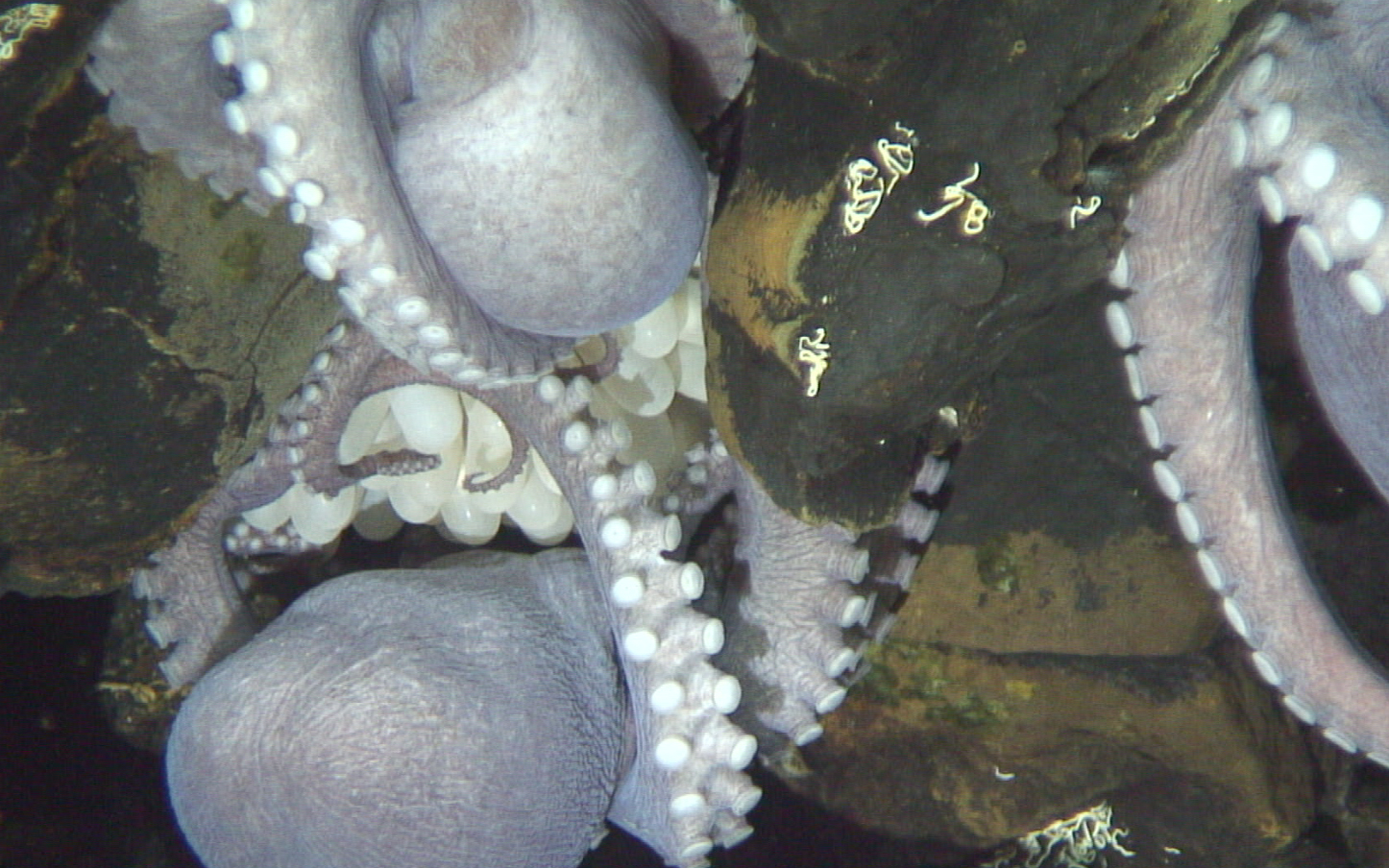

But what were so many octopuses doing in that location? It's highly unlikely that they were drawn to the area because it was a desirable place to lay eggs, the scientists said. Though prior research has shown that elevated water temperatures can speed up egg development, the heat also increases octopuses' metabolic rate, which makes them need more oxygen. And the water seeping from cracks in the rocky outcrop carried just half as much oxygen as the water in the surrounding areas, the study authors wrote.

Together, those factors would spell disaster for mothers and eggs, generating stress levels that could be severe — and likely even lethal, the scientist said.

Perhaps, however, conditions around the rocks weren't so dire when the mothers initially attached their eggs, the researchers suggested. The flow of warmed, oxygen-poor liquid may have been weaker or not even present when the octopuses first arrived, but then, once their eggs were in place, they didn't want to abandon them.

It's also possible that these individuals were forced to relocate into an undesirable neighborhood because of overcrowding in cooler, more-hospitable parts of the rocky outcrop. In this scenario, the females would simply have had no choice but to move to the hotter, low-oxygen area to lay their eggs, the scientists reported.

Given that this group of stressed octopus moms was so large, it would make sense that an even bigger population was thriving nearby, Voight suggested in the statement.

"Octopus females only produce one clutch of eggs in their lives. In order for this huge population to be sustained, there must be even more octopuses to replace the dying mothers and eggs that we can see," Voight said.

Wheat and the study's lead author Anne Hartwell, an oceanographer affiliated with Ohio's University of Akron and the University of Alaska Fairbanks, even reported seeing octopus arms extending from within cracks in the outcrop, suggesting that octopuses could have been lurking in cavities inside those cracks, where the water was cooler and more oxygen-rich, Voight added.

For now, the mystery of the doomed octopus nursery remains unsolved. But finding the gathering gave researchers an exciting glimpse of previously unseen octopus behavior, along with a reminder of how much scientists have yet to learn about life in the unexplored ocean depths, Wheat said in the statement.

"This is only the third hydrothermal system of its type that has been sampled, yet millions of similar environments exist in the deep sea," Wheat said. "What other remarkable discoveries are waiting for us?"

The findings were published online March 28 in the journal Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.