Nubian Stone Tablets Unearthed in African 'City of the Dead'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

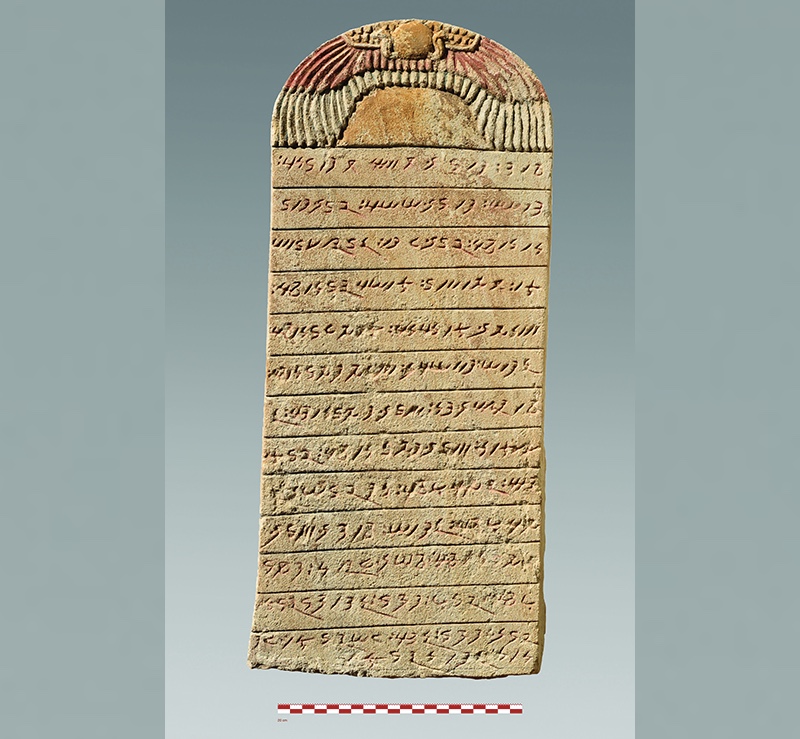

A huge cache of stone inscriptions from one of Africa's oldest written languages have been unearthed in a vast "city of the dead" in Sudan.

The inscriptions are written in the obscure 'Meroitic' language, the oldest known written language south of the Sahara, which has been only partly deciphered.

The discovery includes temple art of Maat, the Egyptian goddess of order, equity and peace, that was, for the first time, depicted with African features. [In Photos: Beautiful Pyramids of Sudan]

Ancient civilization of Meroe

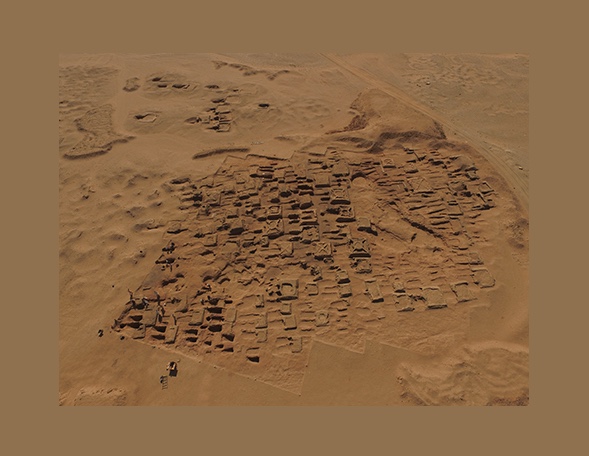

Scientists investigated the archaeological site of Sedeinga, located on the western shore of the Nile River in Sudan, about 60 miles (100 kilometers) north of the river's third "cataract," or set of shallows.

Archaeologists first heard of the site from the tales of 19th-century travelers, who described the remains of the Egyptian temple of Queen Tiye, the chief wife of Amenhotep III and one of the most illustrious queens of ancient Egypt, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Amenhotep III's reign from about 1390 B.C. to 1353 B.C. marked the zenith of ancient Egyptian civilization — in both political power and cultural achievement, according to the BBC.

The sandy area was once part of ancient Nubia, known for rich deposits of gold. Nubia hosted some of Africa's earliest kingdoms, and a few even ruled Egypt as pharaohs, according to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

The site of Sedeinga is home to a large necropolis, known as the "city of the dead," stretching more than 60 acres (25 hectares). It holds the vestiges of at least 80 brick pyramids and more than 100 tombs from the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe, which lasted from the seventh century B.C. to the fourth century A.D. These kingdoms mixed the cultures of Egypt and the rest of Africa in ways still seen in Sudan today, researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Napata and Meroe formed a civilization known as the kingdom of Kush by their ancient Egyptian neighbors. Meroitic, the language of Meroe, borrowed written characters from ancient Egyptian. [Photos: Royal Nubian Statue With Egyptian Hieroglyphics]

"The Meroitic writing system, the oldest of the sub-Saharan region, still mostly resists our understanding," Vincent Francigny, an archaeologist at the French Archaeological Unit Sudan Antiquities Service, and co-director of the Sedeinga excavation, told Live Science. "While funerary texts, with very few variations, are quite well-known and can be almost completely translated, other categories of texts often remain obscure. In this context, every new text matters, as they can shed light on something new."

Huge cache of inscriptions

Now, the scientists revealed they have unearthed the largest collection of Meroitic texts yet. The inscriptions are funerary in nature.

"Every text tells a story — the name of the deceased and both parents, with their occupations sometime; their career in the administration of the kingdom, including place names; their relation to extended family with prestigious titles," Francigny said.

From these inscriptions, "we can, for example, locate new places, or guess their possible locations, or learn about the structure of the religious and royal administration in the provinces of the kingdom," Francigny said. The texts "also tell us what kind of town or settlement was connected to the cemetery we are excavating," he said.

Based on evidence from texts, the site's context, and numerous imported goods found in the graves there, the researchers think Sedeinga was a key place for commercial roads that avoided the meandering and the cataracts of the Nile to the north "to go straight to Egypt through desert roads," Francigny said. "The town would have developed and become wealthy around this activity."

The researchers also discovered numerous samples of decorated sandstone, including chapel art depicting the Egyptian goddess Maat with Nubian features.

"Meroe was a kingdom where, among others, some Egyptian cultural and religious concepts were borrowed and adapted to local traditions," Francigny said. "We should not see Meroe as a passive recipient for foreign influences — instead, Meroites were very selective about what they could borrow to serve the purpose of the royal family and the development of their pharaonic, but non-Egyptian, society."

High-ranking women

The scientists noted that a number of artifacts at Sedeinga were dedicated to high-ranking women. For instance, one stele — an upright decorated slab of stone — in the name of a Lady Maliwarase described her as the sister of two grand priests of Amon, and as having a son who held the position of governor of Faras, a large city bordering the second cataract of the Nile. In addition, a tomb inscription described a Lady Adatalabe, who hailed from an illustrious lineage that included a royal prince.

In Nubia, a matrilineal society, the tracing of one's descent through the female line was "an important aspect in royal family lineages," Francigny said. For instance, "at Meroe, with the figure of the 'candace,' a sort a queen mother, women could, in the royal context, play an important role and be associated with the exercise of power. It is unclear if, at a lower level, women could also play key roles in the administration of the kingdom and the religious sphere."

Intriguingly, on several occasions at archaeological sites related to the kingdom of Meroe, the scientists noted that Meroites were sometimes fascinated with random items with unusual shapes.

"For example, near temples where only priests could enter, it is not unusual to find places made for popular offerings; these offerings were sometime made of oddly shaped natural stones that seemed supernatural because their shapes look like religious symbols or anatomical parts of the human body," Francigny said. "We even found some inside of the most sacred room, the 'naos,' of some Meroitic temples, near the statues of the gods."

In the future, the researchers hope to locate graves dating back to the earliest stages of the site, "during Egyptian colonization," Francigny said. "Unfortunately, in this region the Nile moves toward the east," and so slowly eats away at the excavation site, "which means that there is likely a chance that the settlement that was close to the river was completely destroyed," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus