8 Reasons Why We Love Tardigrades

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

They're adorable and indestructible

It doesn't need to be said, but we'll say it anyway: Tardigrades are amazing.

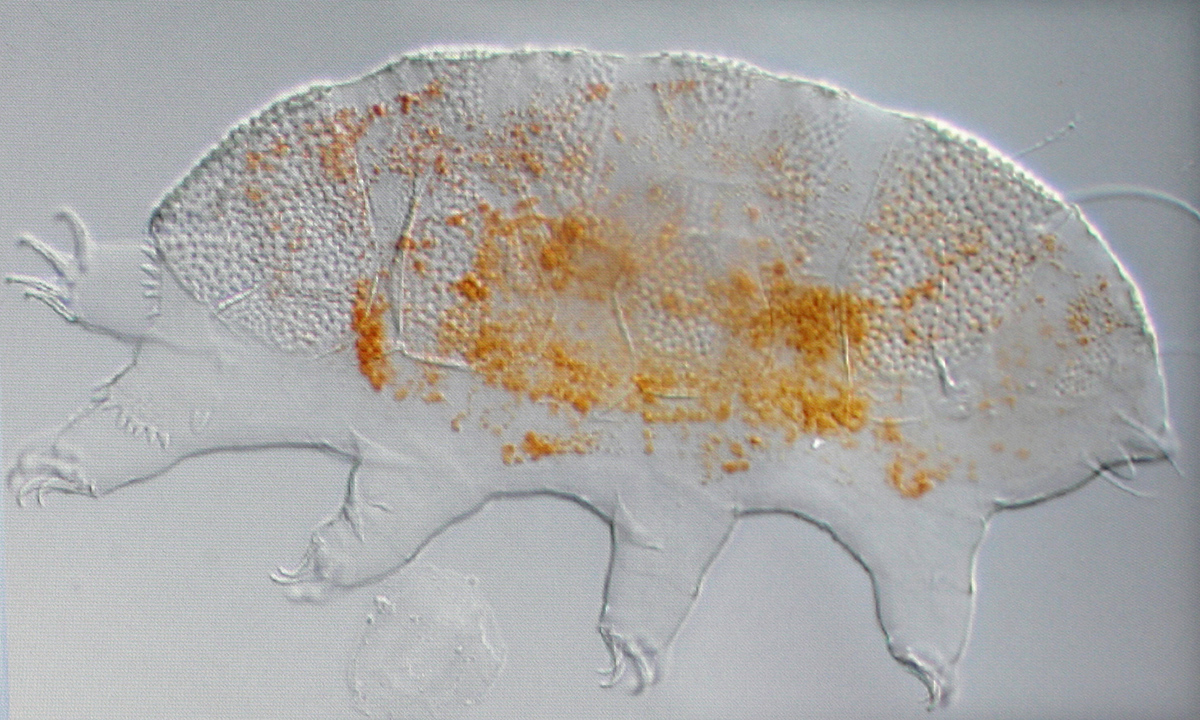

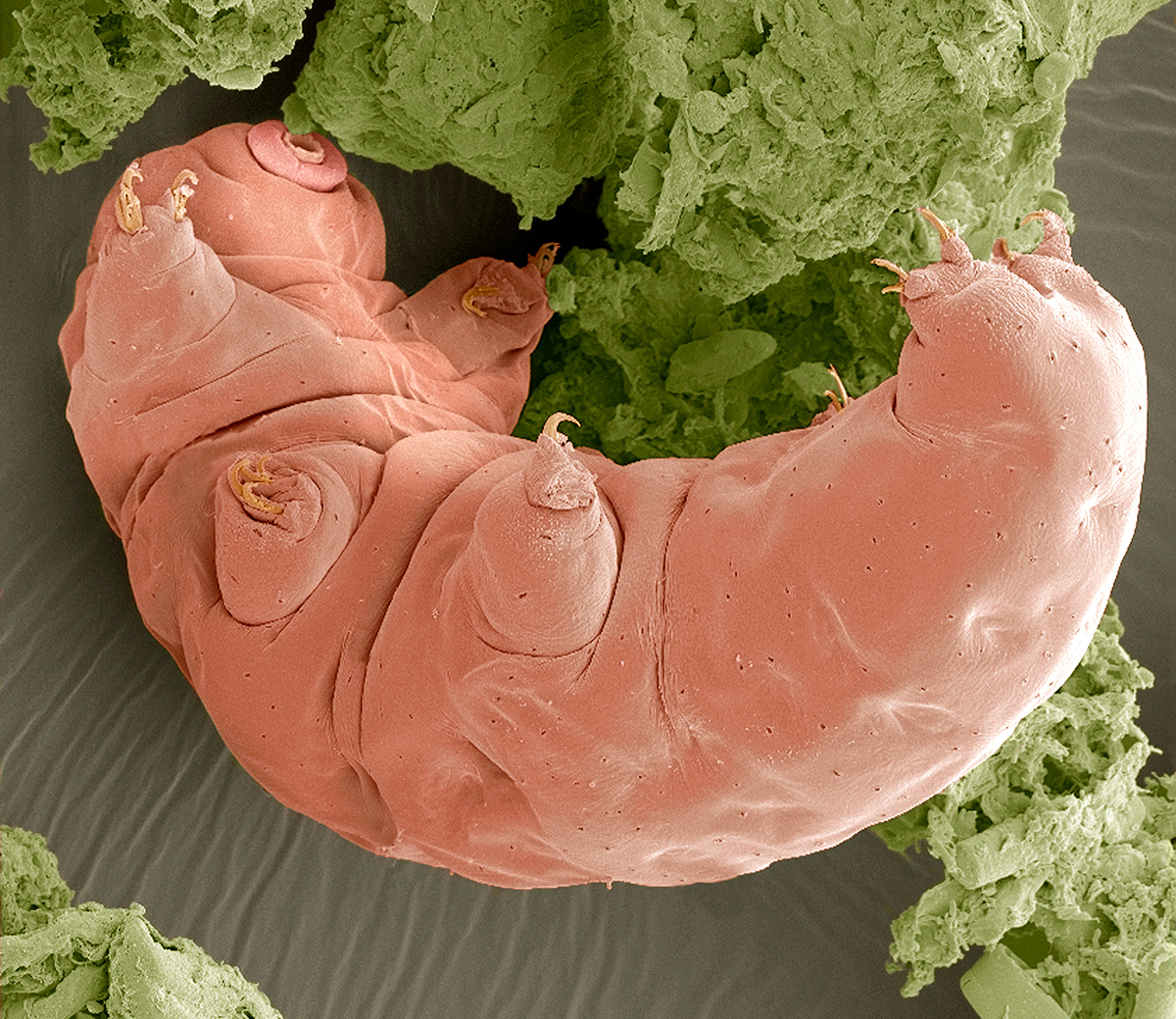

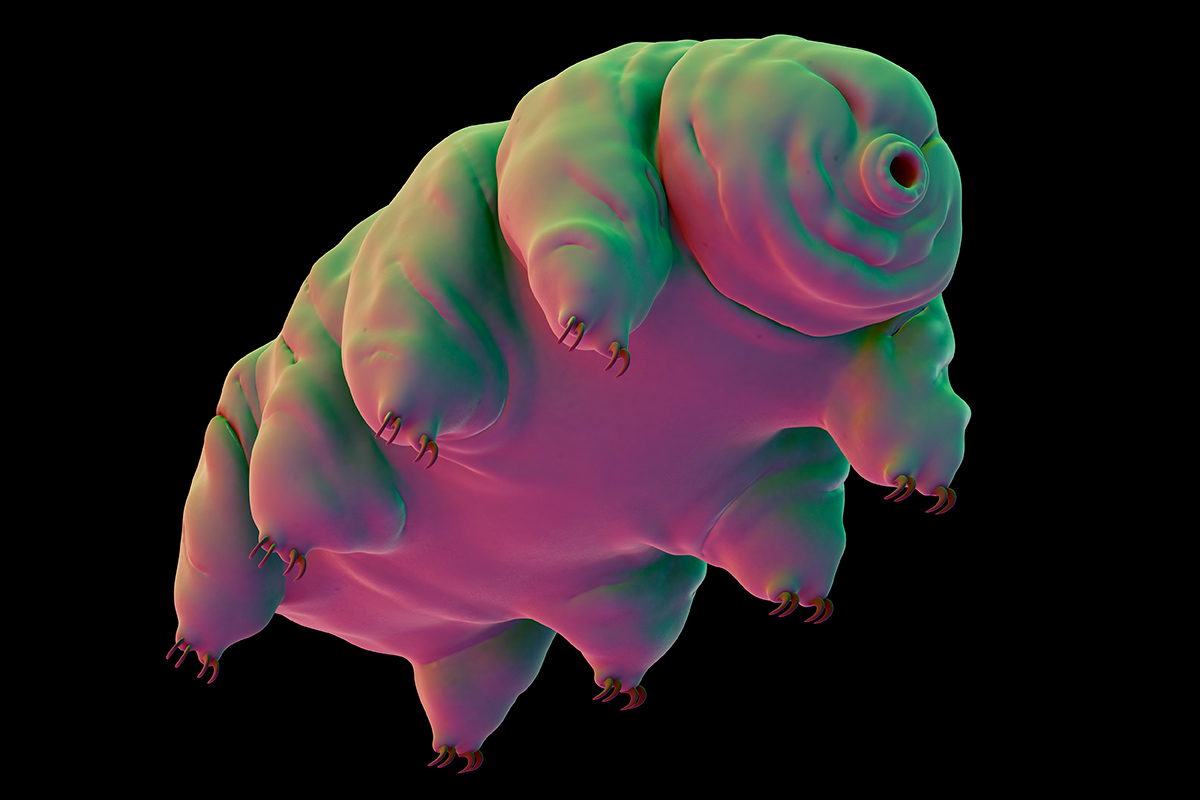

Their tiny, endearingly tubby bodies — about half a millimeter long — can dry out for years at a stretch and then revive with no damage. They can endure extreme heat and cold that would kill most other forms of life, and they can even withstand radiation in space.

Whether you know them as water bears or moss piglets, they’re microscopic bundles of awesomeness, and here are 8 reasons why.

They're basically just heads

You may be familiar with the comics series and T.V. show "The Walking Dead," and you might know the music of "The Talking Heads." But if tardigrades were to form a band, they might call themselves "The Walking Heads."

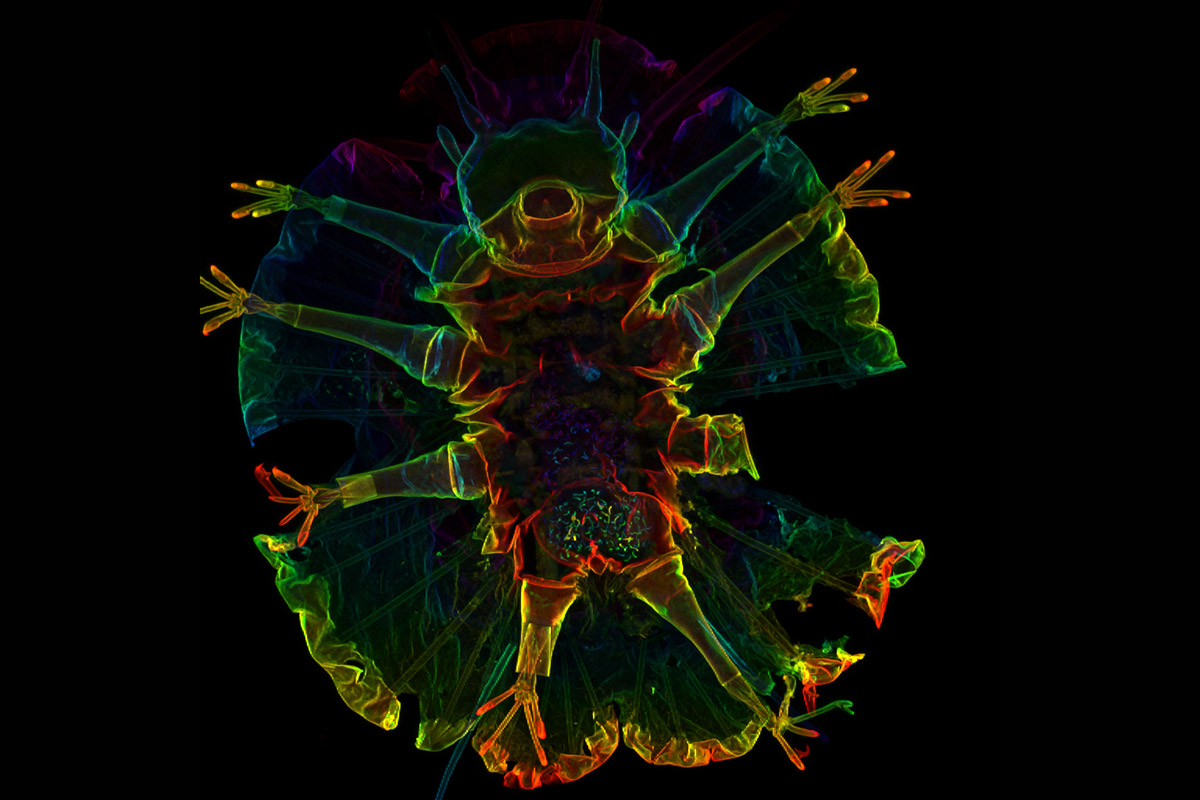

All tardigrades have plump, compact bodies, with four leg-bearing segments — each sporting a pair of clawed limbs — and a stubby head tipped by a toothy mouth ring. But the relationship of their body segments to the bodies of other arthropods has proven tricky to nail down, and the explanation might be that tardigrades are actually just heads with legs, researchers noted in a study published in 2016 in the journal Cell Biology.

At some point in their evolutionary past, tardigrades lost several genes linked to the development of body segments, and along with that they also lost the body parts that correspond to the thorax and abdomen in other arthropods, the study authors reported. Tardigrades' present "segmented" body plan closely resembles the head segments found in arthropods, showing that when it comes to evolution, there's more than one way to get a head.

They lay eggs topped with grasping "spaghetti"

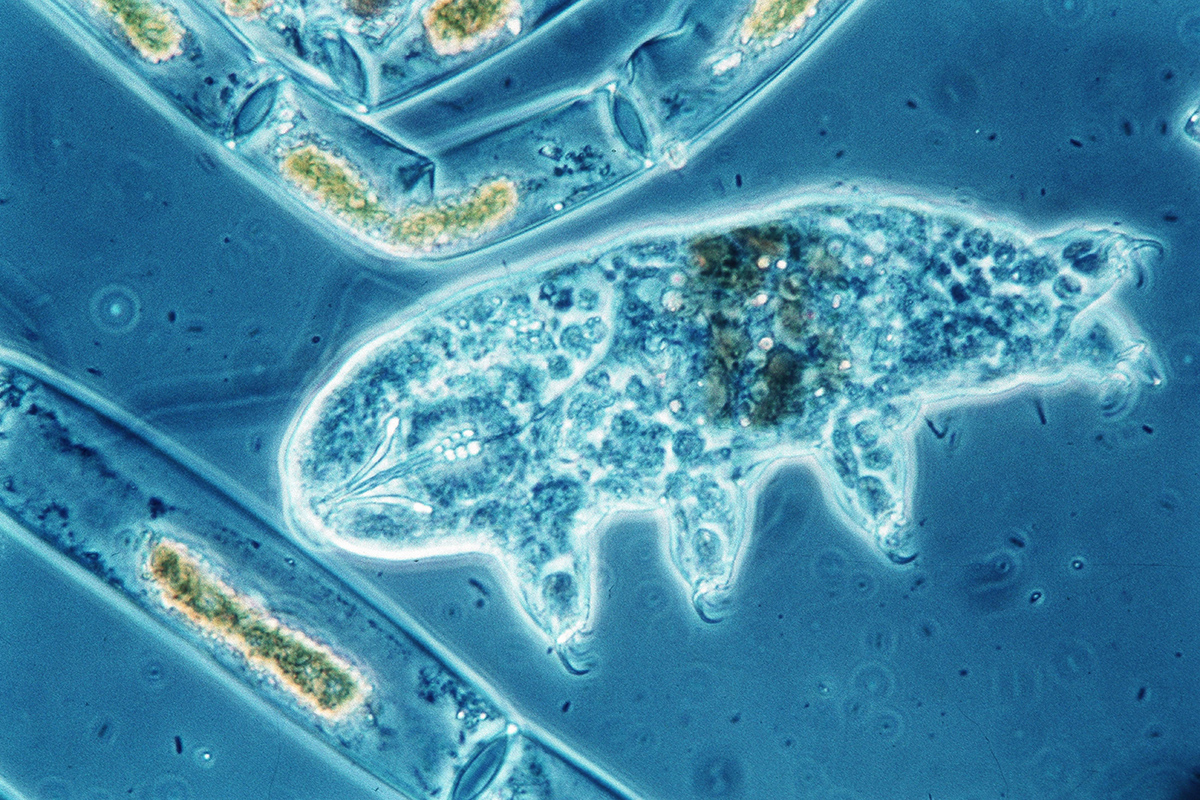

Tardigrades can live just about any place on Earth where there's water, and a new species was recently discovered in a parking lot in Japan.

There are more than 1,000 known tardigrade species, and Macrobiotus shonaicus became the 168th species from Japan when it was described in a study published Feb. 28 in the journal PLOS ONE. Tardigrades are often found living in moss and lichens, and the new species turned up in a moss sample that the study's lead author had collected from a parking lot near his apartment, which was "quite surprising," he told Live Science in an email.

But the oddest thing about this tardigrade was not its urban location, but its eggs, which were topped with wiggly, spaghetti-like tendrils. These noodly appendages may help to attach the eggs to surfaces after the tardigrade leaves them, the study authors reported.

They can withstand intense heat and freezing cold

Hardy tardigrades can survive punishing conditions that would be lethal to most living things, weathering temperatures up to 300 degrees Fahrenheit (149 degrees Celsius) and as low as minus 328 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 200 degrees Celsius).

They do this by expelling all the water from their bodies, retracting their stubby limbs, and curling up into dried-out balls, a type of suspended animation known as a "tun." When the danger has passed, they rehydrate and return to normal, with seemingly no ill effects.

Recently, scientists discovered that a certain type of protein that is unique to tardigrades may be the secret to their recovery prowess. Tardigrade species that had a constant supply of this protein were more successful at recovering from a tun state than their cousins that did not always produce the protein, according to a study published in March 2017 in the journal Molecular Cell.

They have no childhood, hatching from their eggs fully formed

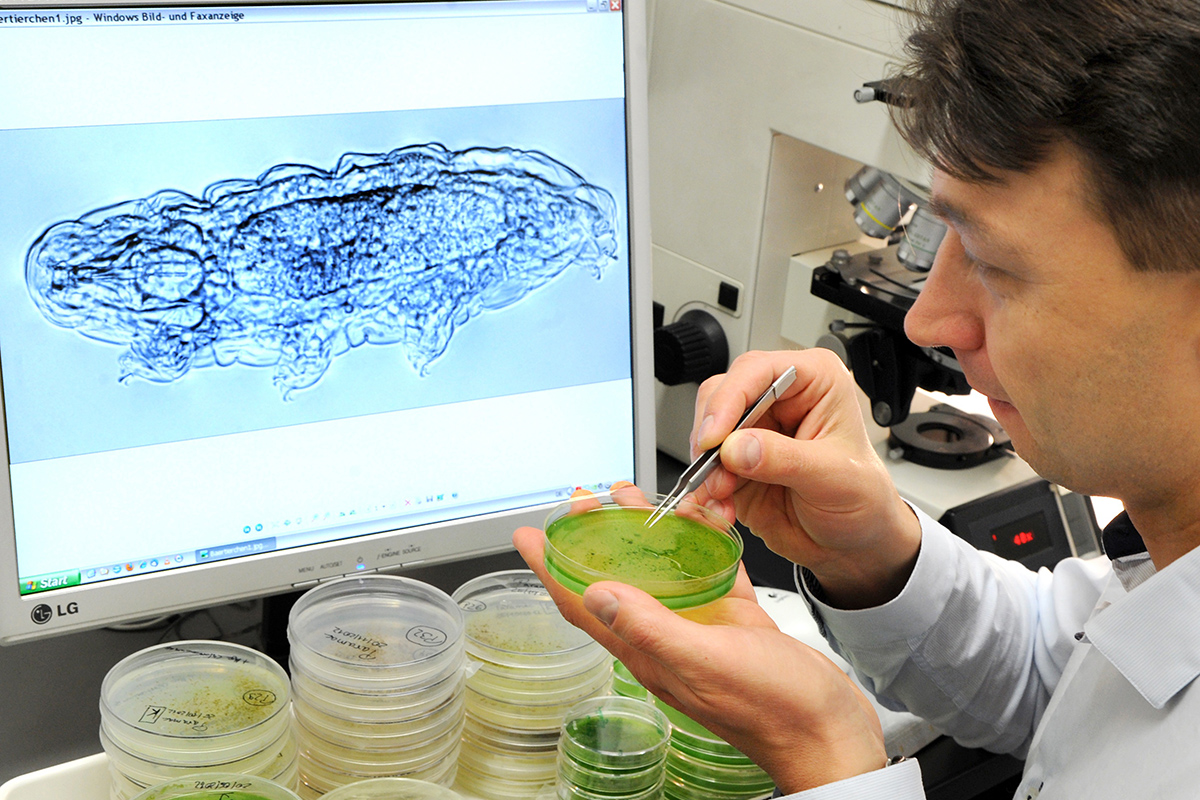

Researchers have long been fascinated by tardigrades, which have been around for at least 500 million years, and in 1938 scientists learned that minuscule water bears hatch from their eggs in their adult forms.

Many arthropod relatives of tardigrades have a distinct larval stage as juveniles, in which their bodies look dramatically different from those of adults — picture the chubby grubs that grow up to be termites, or the caterpillars that metamorphose into moths or butterflies.

Hatchling tardigrades, on the other hand, look exactly like adult tardigrades, if a little smaller. Molting occurs several times during tardigrades' lifetime, during which they shed their skins to accommodate their growing bodies, but they maintain the same body plan throughout their lives, according to a study published in May 2015 in the journal Polar Biology.

They have a built-in "space suit"

Not only can tardigrades survive exposure to extreme temperatures, they can also withstand boiling liquids and pressures up to six times that at the ocean's deepest regions. But tardigrades' survival superpowers extend even further, beyond conditions on Earth to encompass the hazards of space travel.

Tardigrades can recover after facing unfiltered solar radiation and space's vacuum, adding them to an "exclusive and short list of organisms" capable of doing so, researchers reported in September 2008 in the journal Current Biology.

Dried-out adult tardigrades and eggs in two species — Richtersius coronifer and Milnesium tardigradum — were exposed to space vacuum and radiation over 10 days at low-Earth orbit, about 846,000 to 922,000 feet (258,000 to 281,000 meters) above sea level. The specimens were then later resuscitated and examined.

Both species survived "very well" after exposure to the vacuum of space, though survival among those exposed to radiation was "significantly reduced," the study authors reported.

They can be frozen for decades and still reproduce when they wake up

Two Acutuncus antarcticus tardigrades that spent over 30 years in a researcher's freezer were successfully resuscitated, and one of them almost immediately started getting busy.

The tardigrades were retrieved from a piece of moss that had been stored at minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 20 degrees Celsius) since 1983, and the animals were in a suspended state known as "cryptobiosis," showing no signs of their normal metabolic processes.

But just one day after rehydration, one of the tardigrades was stretching its legs, and by the time 22 days had passed, researchers saw eggs inside its body. It eventually laid 19 eggs, producing 14 live hatchlings.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They inspire new kinds of glass

A new type of glass that could improve the efficiency of solar cells and LED lights owes its inspiration to tiny tardigrades.

When these microscopic creatures expel all the water from their bodies to enter their suspended "tun" state, special proteins that are only found in tardigrades turn the fluid inside their cells into a glasslike substance, protecting biological structures until the tardigrade can be rehydrated and revived.

Researchers were intrigued by this ability, which led them in 2015 to develop a glass material with a molecular structure that was highly organized, more akin to crystals than glass. These "oriented" molecules could make glass more efficient at capturing and directing light, which could improve the performance of devices such as optical fibers, LEDs and solar cells, the scientists said in a statement.

They may outlive humanity, this planet, and possibly even the sun

People joke about "our insect overlords," but when the curtain comes down on our solar system, it may well be tardigrades that have the last laugh.

A team of scientists considered a series of doomsday scenarios that would be catastrophic for humanity, including nearby supernovas, the expansion of our own sun to a red giant star, and a massive asteroid colliding with Earth.

In every scenario, tardigrades were just fine, confirming that when it comes to life on Earth, they are as close to indestructible as it gets, the researchers said in a statement. We can therefore all rest assured that even if a sequence of devastating events — or one enormous planet-killing disaster — manages to wipe out most species alive today, the tardigrades will still somehow manage to come out on top, ensuring that "life as a whole will go on," the scientists concluded.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus