What Is the World's Oldest Photograph?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

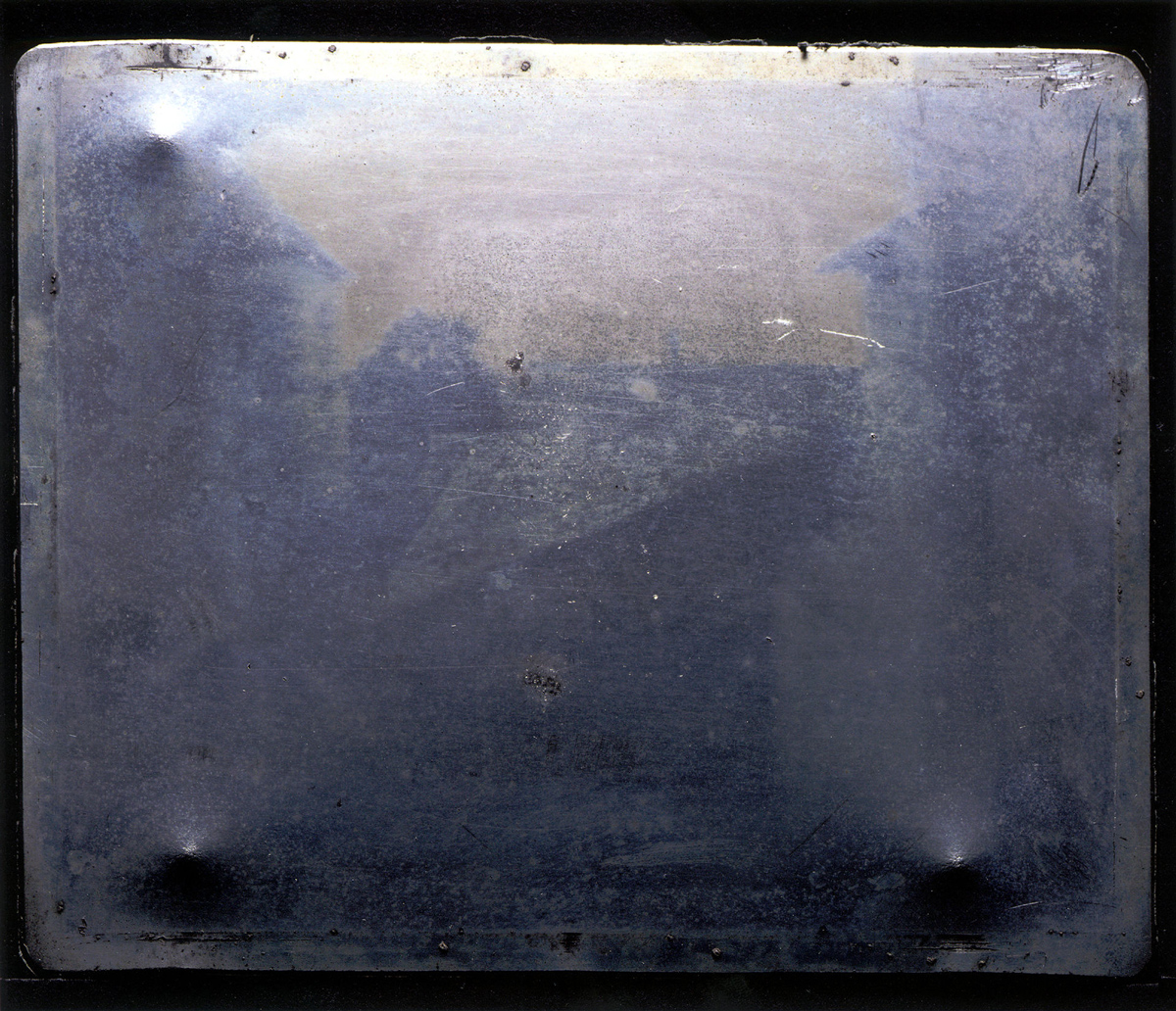

The world's oldest surviving photograph is, well, difficult to see. The grayish-hued plate containing hardened bitumen looks like a blur.

In 1826, an inventor named Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the photo, which shows the view outside of "Le Gras," Niépce's estate in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France.

Niépce had already learned that if you put asphalt dissolved in lavender oil onto a pewter plate, place an object (like a leaf from a tree) on the plate and expose the plate to sunlight, then the asphalt would harden the most on areas of the plate that were not covered by the object (and were exposed to the most sunlight). If you then wash the plate, the unhardened asphalt beneath the object will rinse off showing an impression of the object that covered it, explained Mark Osterman, a photographic process historian at the George Eastman Museum, in an article published in "The Concise Focal Encyclopedia of Photography" (Elsevier, 2007). [19 of the World's Oldest Photos Reveal a Rare Side of History]

To take the world's first photograph, Niépce used bitumen of Judea (a substance used since the time of the ancient Egyptians) mixed with water and put it onto a pewter plate, which he then heated (already hardening the substance onto the plate to some degree). He then put the plate in a camera and pointed it out a second story window. He left the camera alone for a long period of time, perhaps as long as two days. In that time, the bitumen on parts of the plate that received the most sunlight hardened a little bit more than areas of the plate that received less sunlight, such as parts of the plate that were facing a building or dark part of the horizon. Niépce then washed off the unhardened parts of the plate to produce a picture that can barely be seen. It is now housed in the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas.

It "probably took two days of exposure to record the outline of the horizon and the most primitive architectural elements of several buildings outside and below the window," wrote Osterman.

While this "heliographic" technique (as Niépce called it) produced the world's oldest known photo, the image quality was poor and took a long time to produce noted Osterman. It wasn’t until Niépce teamed up with another inventor, named Louis Daguerre, that the daguerreotype, a photograph that had a much better image quality and didn't take as long to produce, was invented. Niépce died in 1833, before the technique was fully developed, but Daguerre pressed on with the help of Niépce's son, Isidore Niépce, eventually finding that a silver-iodide plate exposed to mercury fumes could produce a photo within minutes.

"Daguerre discovered that the silver-iodide plate required only a fraction of the exposure time and that an invisible, or latent, image [could] be revealed by exposing the plate to mercury fumes," noted Osterman in his article. The plate could then be placed in a mixture of sodium chloride that stabilized the image, Osterman wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By 1838, Daguerre was taking photos of objects and buildings, and in 1839, the French government awarded Daguerre and Isidore Niépce lifetime pensions in exchange for sharing their photography technique. The use of daguerreotype photography spread quickly around the world, encouraging other inventors to find new and better ways of taking photographs and, in time, developing moving pictures (movies).

For instance, changes in the chemicals put on plates resulted in shorter exposure times, making it easier to take pictures of people while capturing more details of the person or object being photographed. Also, techniques that used paper rather than silver plates were developed, reducing the cost of taking photographs. Improvements in the cameras that the plates (and later paper) were placed in resulted in photographers becoming more mobile and able to take a wide variety of shots, including close-ups and pictures taken from far away.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus