Anthrax & Plague: How 1 Vaccine Could Protect Against 2 Bioterror Threats

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A single vaccine could potentially protect against two of the biggest bioterrorism threats — plague and anthrax, an early study suggests.

The researchers tested a new "bivalent" anthrax-plague vaccine in mice, rats and rabbits that were later exposed to plague and anthrax at the same time. They found that the vaccine offered 100 percent protection against both typically deadly diseases.

"Our studies provide the first proof-of-concept data that a bivalent anthrax–plague vaccine can potentially protect vaccinees in the event of a bioterror attack," with weaponized anthrax or plague bacteria, the researchers wrote in the June 26 issue of the journal Frontiers in Immunology. "This bivalent vaccine, therefore, is a strong candidate for stockpiling as part of our national preparedness against bioterrorism threats," they said.

However, additional studies in humans are still needed to determine the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, the researchers said. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

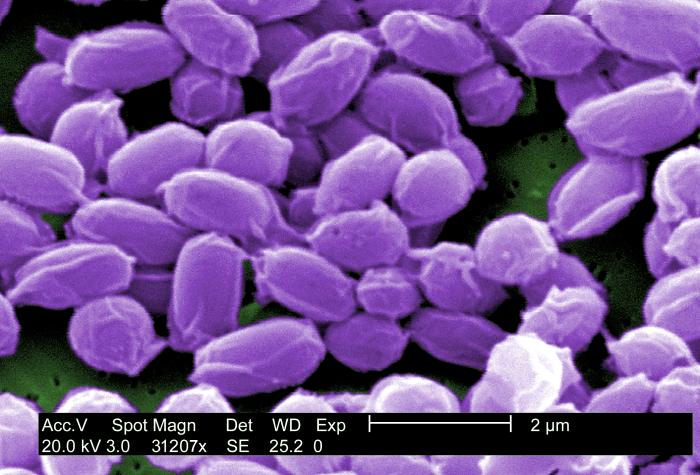

Anthrax is caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, and plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Both anthrax and plague are considered potential agents for use in a biological attack, in which microbes are intentionally released to sicken or kill people. In addition, both anthrax and plague are lethal, typically causing rapid death in three to six days unless the victim receives antibiotics within 24 hours of their symptoms, according to the study.

"Intentional release of these organisms as a bioweapon could lead to massive deaths, public panic and social chaos," the researchers said.

The best way to counteract such an attack would be to vaccinate people before the attack, they said. Vaccines could also be given after an attack to minimize further casualties and reduce harms from future attacks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, in the United States, there is no vaccine against either anthrax or plague that's approved for the general population. (There is an anthrax vaccine that's recommended only for people at increased risk of being exposed to anthrax, including some laboratory workers and military personnel.)

In the new study, the researchers designed a vaccine containing three proteins — two from plague bacteria and one from anthrax bacteria. The three proteins were joined so that they formed one single, large protein. The idea is that the body can then build up immunity to those proteins, and when exposed could launch a successful attack against them.

The researchers immunized eight mice with their vaccine, and 23 days later, exposed the mice to anthrax through an injection, and pneumonic plague (the most serious form of plague that can spread through the air) through a nasal spray. A separate group of control mice was exposed but not vaccinated.

All of the mice that received the vaccine survived, whereas all of the mice that were not vaccinated died within two days of being exposed to both bacteria, the study found.

Experiments in rats had a similar result, with all of the vaccinated rats surviving exposure to plague and anthrax, and all of the unvaccinated animals succumbing to the diseases.

The researchers also tested their vaccine in rabbits, because rabbits are a better animal model for experiments with "aerosolized" anthrax that can be inhaled. All 10 rabbits that were given the vaccine survived exposure to aerosolized anthrax, while all of the unvaccinated rabbits died within two to four days of exposure to anthrax.

This study is the first to show that a vaccine can completely protect animals against simultaneous exposure to both anthrax and plague, the researchers said.

If the new vaccine is successful in future clinical trials, it "could streamline efforts to stockpile a biodefense vaccine" against both anthrax and plague, they said.

The study was conducted by researchers at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland; and the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus