After 75 Years, Anne Frank's Diary Still Holds Lessons for Us All

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

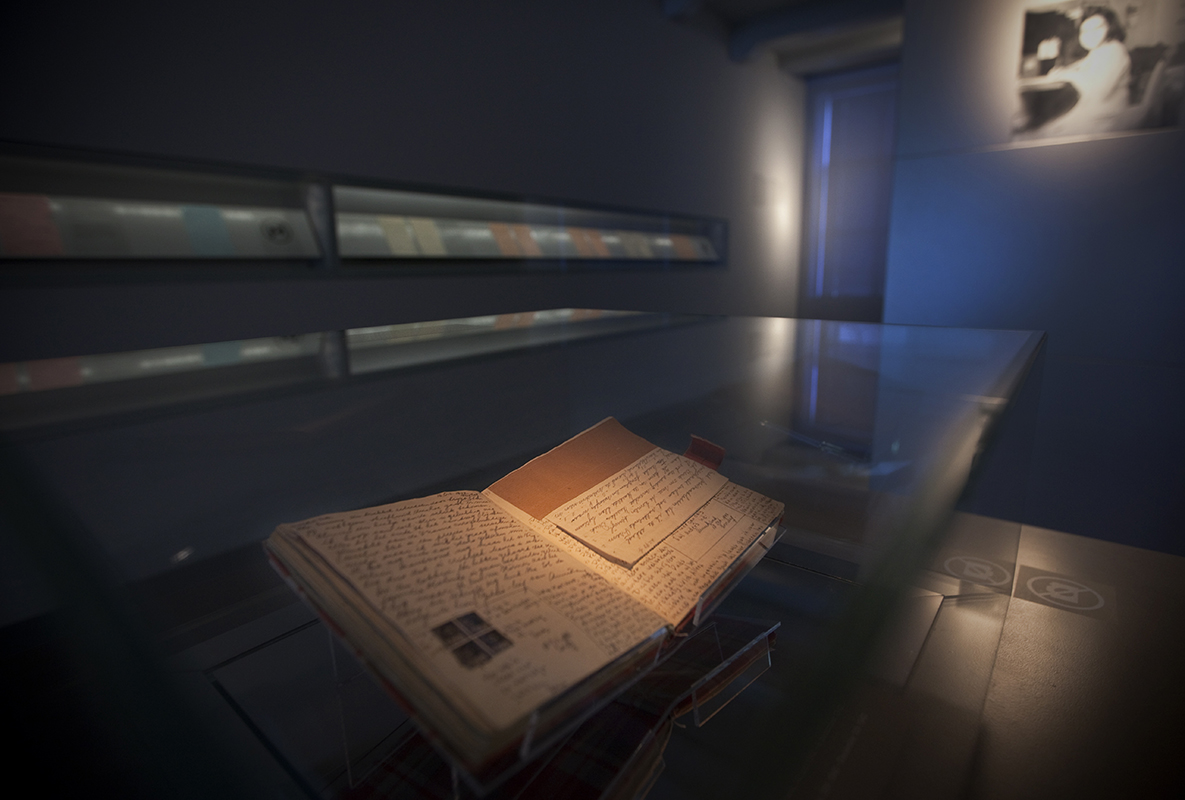

On June 12, 1942, a young Jewish girl named Annelies Marie Frank made her first entry in her now-famous diary, which had been given to her as a birthday present. Little did she know that it would be read and discussed for generations to come, and that through her private musings she would become an unforgettable symbol of the tragedy of the Holocaust for millions of readers around the world.

Teenage Anne Frank, who was only 16 when she was killed in the Nazi death camp Bergen-Belsen, wrote in this diary throughout the two years she spent in hiding with her family and four other Dutch Jews, between 1942 and 1944. Their refuge was a secret attic apartment, concealed behind her family's business office in Amsterdam.

During that time, Anne recorded her innermost thoughts and painfully honest observations from the "achterhuis" — the "Secret Annex," as she called her hidden home. These diary entries reflected the tension and danger she and her family faced from both the Nazis and Dutch sympathizers, but they also shared her youthful idealism and thoughtfulness, according to diary excerpts. Anne not only documented day-to-day life for eight people sharing a cramped hiding place and fearing discovery at any moment; she also captured their moments of tenderness and humor, and their hopefulness even in the face of a terrible reality. ['Dear Diary': 14 Journal Keepers Who Made History]

"Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl" was published in Dutch in 1947, and an English edition followed in the U.S. in 1952, according to the Anne Frank House museum. Following the U.S. publication, the book was promptly declared "a classic" as well as a profoundly intimate and moving story, in a review published that year in The New York Times.

"Anne Frank's diary simply bubbles with amusement, love, discovery," the Times reported. "It has its share of disgust, its moments of hatred, but it is so wondrously alive, so near, that one feels overwhelmingly the universalities of human nature. These people might be living next door; their within-the-family emotions, their tensions and satisfactions are those of human character and growth, anywhere."

Even those earliest readers of Anne Frank's diary could recognize the unique power of her voice, and likely suspected she would not soon be forgotten, according to the Times review.

"Surely she will be widely loved, for this wise and wonderful young girl brings back a poignant delight in the infinite human spirit," the Times wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Indeed, based on her book's popularity — which continued to build over the coming years — Anne was certainly "widely loved." By 1969, her diary had been published in 34 languages and it is currently available in 70 languages. With more than 25 million copies sold, it is one of the most read books in the world, according to the Anne Frank House.

A timeless voice

One remarkable aspect of the book is its consistent impact over time. Anne's diary continues to resonate with readers as strongly as ever, in part because her intriguing personal story also offers insight into a very dark period in human history, Edna Friedberg, a historian with the Levine Institute for Holocaust Education at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, told Live Science.

"For many millions of young people, Anne Frank and her diary is the first point of entry into the complicated world of the Holocaust, and that is in large part due to the voice of a girl — a teenager herself — who is so relatable," Friedberg said.

"She is so smart and reflective, but also so real. She has become iconic of the well-over 1 million Jewish children who were murdered during the Holocaust, but she also transcends that moment, because of her voice," Friedberg said.

As the diary of a teenager, the book is particularly accessible to youthful readers, and serves as a unique and powerful reminder that even in the context of global events, young voices can make a big difference, Friedberg added.

"This is but one of many kid and teen diaries that we have from the Holocaust era," she said. "They remind kids that they have agency, that their take on the world matters, and in a way that transcends the specifics of the time and place." [In Photos: Girls' Hut Found at Nazi Death Camp]

What might have been

In 1944, after the Franks had been in hiding for nearly two years, an announcement on Dutch radio broadcasting from London suggested that diaries kept during the war would be collected and archived for the people of the Netherlands. Anne, who was listening to the broadcast with her family, was inspired to rework her diary and adapt it into a novel, imagining that she would publish it when the war was over and her family emerged from hiding, according to the Anne Frank House website.

Still, she occasionally doubted her abilities as a writer, according to the museum's website.

"In my head it is as good as finished, although it won't go as quickly as that, if it ever comes off at all," Anne wrote in May of that year.

But she never got the chance to develop those ideas. On Aug. 4, 1944, Anne, her family, and their fellows in hiding were arrested by officers with the Gestapo — the Nazi secret police — and were shipped to Auschwitz, a death camp in Poland. Anne and her sister Margot were later transferred to Bergen-Belsen, another death camp in Germany, where they both died of typhus in 1945.

Recently discovered documents reveal that Otto Frank, Anne's father, was in touch with people in the U.S. to obtain visas for his family while they were in hiding, but the potentially lifesaving documents were not granted in time, Friedberg told Live Science.

"When we look at that story and see what might have been, if those visas had been granted, for sure Anne Frank would not be a household name," Friedberg said.

"But she could have given so much to the world," Friedberg added. "And I think through the person of Anne, through her words, we see what was destroyed by the murder of 6 million human beings — the lost promise, creativity and potential, from the failure of the world to respond."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus