Glowing, 'Living' Gloves Could Aid Crime-Scene Investigations

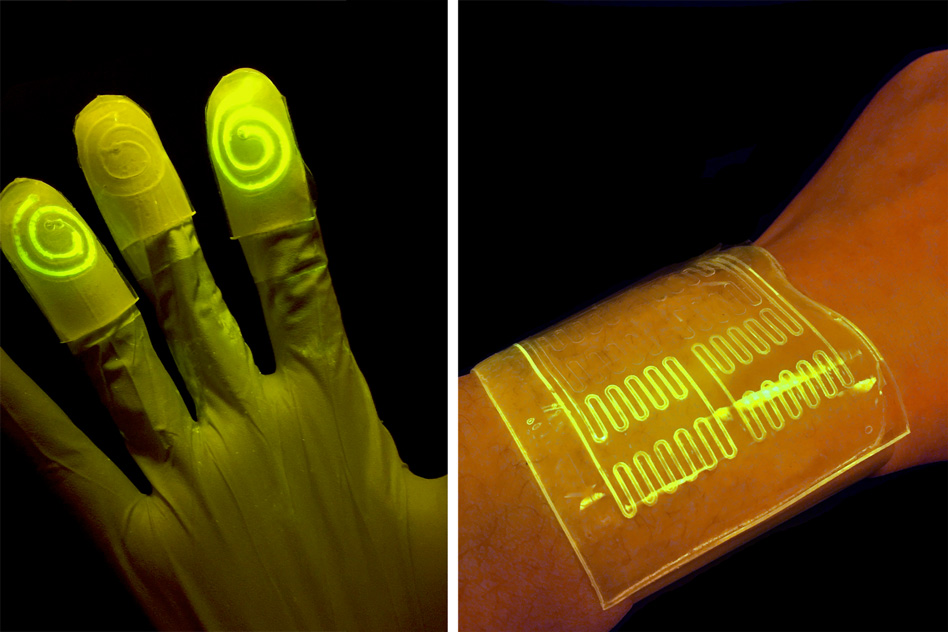

One day, glowing gloves made of a "living material" could replace the "CSI"-style black lights currently used to detect certain substances in crime-scene investigations and other scientific applications, according to a new study.

A team of researchers has bioengineered a "living material" that will light up when in contact with certain chemicals. In the new study, the researchers described the living material — a hydrogel filled with E. coli bacteria cells — and its potential applications. The cells are genetically reprogrammed to light up, using fluorescence, when they come into contact with different chemicals.

So far, the researchers have injected the hydrogel into gloves and bandages, but they say the living substance could be applied to crime scene investigations, medical diagnostics, pollution monitoring and more. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

"With this design, people can put different types of bacteria in these devices to indicate toxins in the environment, or disease on the skin," study co-author Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, said in a statement. "We're demonstrating the potential for living materials and devices."

Though wearable sensors are the goal, the researchers have seen the most success in testing the programmed cells within petri dishes, where the environment can be carefully controlled. Maintaining the living cells when they're deployed in a functioning device has been a main challenge in the team's research.

To find a host for his programmed cells, Lu teamed up with Xuanhe Zhao, an associate professor of civil, environmental and mechanical engineering at MIT. Zhao and his colleagues had studied different hydrogel formulations, and their latest iteration offered the bioengineered bacteria a stable environment. The hydrogel is about 95 percent water, it doesn't crack when it's stretched or pulled and it can fuse to a layer of rubber while still letting in oxygen.

One test of the cell-filled hydrogel included a bandage, or "living patch" that was programmed to respond to rhamnose, a naturally occurring sugar found in plants. The researchers also tested a glove with fingertips that glowed when they came into contact with different chemicals. In both tests, the cells remained stable in the hydrogel and appropriately glowed in response to the chemicals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For future living materials, the team also developed a theoretical model to guide researchers in their designs.

"The model helps us to design living devices more efficiently," Zhao said. "It tells you things like the thickness of the hydrogel layer you should use, the distance between channels, how to pattern the channels, and how much bacteria to use."

The MIT team's living material is described in a study published online Feb. 15 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus