Crocodile Mummy Kept Dozens of Baby Crocs Under Wraps

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

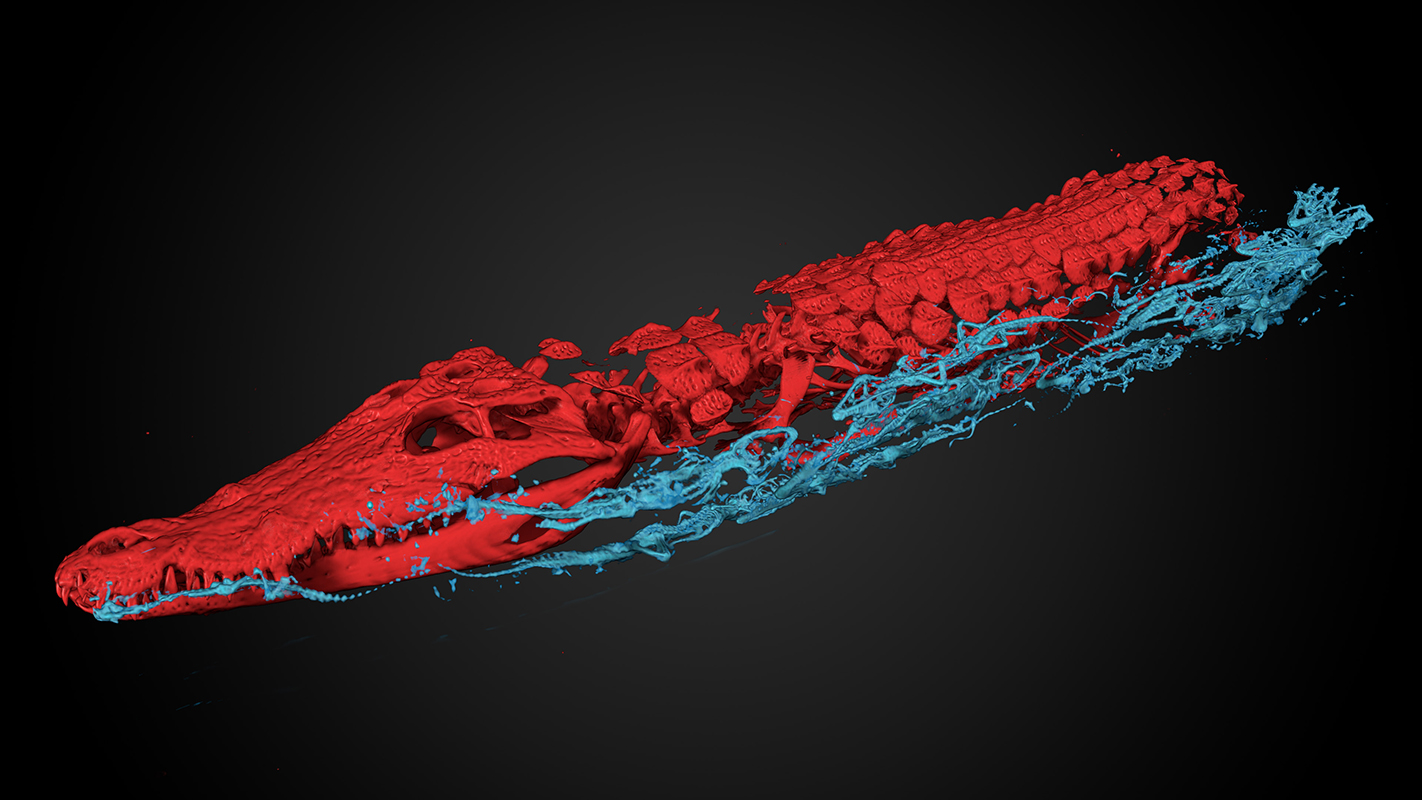

High-resolution scans of a sizable Egyptian crocodile mummy have revealed a secret that the croc had literally kept under wraps for 2,000 years.

There were unexpected stowaways hidden under the mummy's bandages — dozens of baby crocodiles, each one individually swaddled.

Earlier scans of the mummy completed in 1996 had found that the so-called "giant" crocodile, which measures about 10 feet (3 meters) in length, was actually two smaller juveniles, placed together and wrapped to resemble one much larger individual.

But those scans didn't tell the whole story. It wasn't until recently, when additional scans were acquired and carefully scrutinized, that 50 tiny, hidden crocodiles also came to light. [Photos: Giant Crocodile Mummy Packed with Baby Crocs]

The crocodile mummy is part of the Egyptian Collection at the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities (DNMA). The DNMA scientists conducted new 3D X-ray scans of the object, and collaborated with Swedish visualization group Interspectral to create a digital model of the mummy for an interactive "virtual autopsy," which would allow visitors to strip away the mummy's layers and explore what lies beneath.

The 50 baby crocodiles were wrapped in the pine rope bindings that secured the two juvenile crocodiles together, according to a statement released by Interspectral. They were likely all mummified together as an offering to the crocodile god Sobek, and additional plant material, wads of fabric and coils of rope padded them to form a single, massive crocodile shape, DNMA Egyptologists suggested in the statement.

Computed X-ray tomography (CT) technology has improved greatly since the mummy was first scanned in 1996. But although the recently gathered data was more detailed than the older scans, it still required extensive interpretation, Interspectral co-founder Claes Ericson told Live Science in an email. He explained that the technician had already been working with the mummy's data sets when he zoomed in on an unusual detail purely by chance, discovering that it was a tiny skeleton.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's a combination of good hardware (the scanner), good software (Inside Explorer), a good pair of eyes and luck," Ericson said.

To noninvasively explore fragile specimens such as this one, researchers and museum conservators use a variety of scanning technologies, including laser scanning, photogrammetry, CT scans and lidar (light detection and ranging), Ericson said. But only CT scanning captures internal and external structures in three dimensions. In this case, the scans allowed DNMA curators to observe details in the mummy that previously went undetected, presenting them with exciting new information about an important artifact.

"When we started work on this project, we weren't really expecting any new discoveries," a DNMA curator said in a statement published Nov. 15. "What was intended as a tool for museum visitors has yet produced new scientific insights."

The crocodile mummy interactive and the newly renovated DNMA Egyptian galleries opened to the public Nov. 18.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus