Rich Streams of Bacterial Life Found on Skin

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

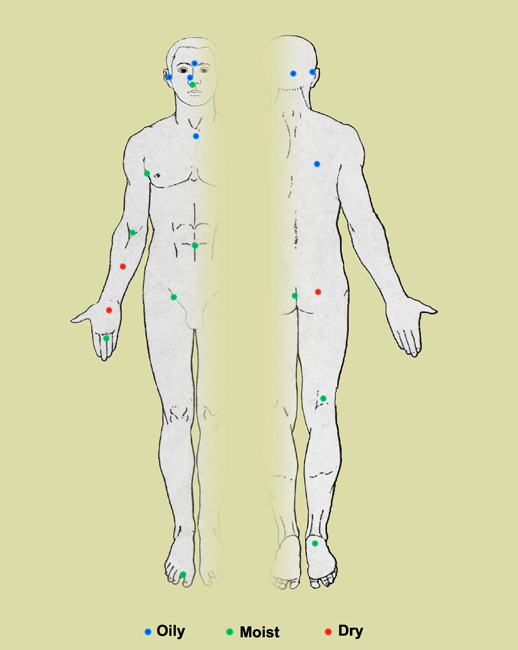

Human skin hosts a huge, diverse population of bacteria that changes based on local skin conditions such as dry, moist and oily.

Such findings come out of the Human Microbiome Project, which involves researchers working to genetically identify the vast swarm of microbes living in and on the human body. Part of the project focuses on the human skin.

The latest study discovered a wide array of bacteria at 20 separate skin sites, depending on the local skin's "ecosystem," said Julia Segre, a molecular biologist at the National Human Genome Research Institute and senior author on the research detailed in the May 29 issue of the journal Science.

"We use the analogy that the skin is like a desert with large dry areas, but then there are these streams, or creases of your body," Segre said. "There's much richer bacterial life in the streams."

Disturbances in the bacterial balance can lead to foreign species moving in and possibly contributing to human diseases. But at the same time, researchers hope to figure out how to promote a normal, healthy bacteria population — once they understand what constitutes "normal" and "healthy" in most people

A skin ecosystem

The human skin contains dry, moist and oily areas that represent very different environments for bacteria. And a few locations such as the belly button or nose represent "oases" where many bacteria can gather.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers saw the most stable bacteria populations in ear and nose samples from 10 healthy people, and the most wildly different samples from behind the knee. They also discovered the most stable populations on oily skin, compared to the greater variation found in dry and moist areas.

Knowing that the bacteria inside the bend of an elbow are similar to bacteria behind the knee could provide clues about common skin diseases, Segre said.

"Often if a kid develops eczema in the bend of elbow, they also develop it in the bend of the knee," Segre told LiveScience. "This begins to give us ideas of why diseases might manifest in those locations."

The part of the human skin that can claim most diversity is the forearm, with 44 bacteria species on average. By comparison, behind the ear saw only 19 bacteria species on average.

However, the most stable skin sites look more similar across different people than separate skin sites on one person. That means strangers often share the same bacteria living on their underarms, even as two separate sites on the same person contain wildly different bacteria.

Superorganism

Researchers have known that the human body resembles a superorganism that has 10 bacterial cells for every one human cell. But finding out what those bacteria are has proved tricky.

Traditional culturing methods use samples to grow bacteria colonies in the lab. The trouble arises because no one knows if those lab-grown populations really reflect the bacteria populations living on the human skin.

"Sometimes you found one bacterial isolate out of 500 [in culture], when the same site on the body has one bacterium out of five," Segre said.

Using newer gene sequencing technology, Segre and her colleagues identified 112,000 bacteria gene sequences that belonged to 205 different genera or bacteria families. It's a first step toward establishing a benchmark about what a healthy bacterial community looks like on the human body.

Nature abhors a vacuum

That healthy bacterial community may have changed drastically, though, with the rise of modern medicine. Antibiotics can indiscriminately wipe out both "bad" bacteria and normal bacteria populations that colonize the human skin.

Such mass destruction of normal, healthy bacteria can then leave an open door for strange bacteria to move in, and possibly cause more health problems because of the imbalanced bacteria population.

"Much as I love sanitation, we need to lose this idea that we need to sterilize our bodies," Segre said. "Nature abhors a vacuum."

Even defining "bad" bacteria may simply depend on whether bacteria are in the right place, Segre explained. For instance, normal skin bacteria that get inside the body during hospital procedures can cause infections.

"Bacteria have a kind of yin-yang, where they're healthy in one setting but not healthy in another," Segre added. "But the goal of most of these bacteria is to live in harmony with us."

Future skin health

The next step for this part of the Human Microbiome Project involves expanding its sampling of skin bacteria. After all, a healthy person's skin bacteria may differ greatly from the bacteria populations living on kids or the elderly.

The bacteria could even differ for pet owners, or people who grow up in cities as opposed to in rural areas, Segre pointed out. Additional research could even try to understand how human babies go from a sterile environment in the womb to acquiring their own healthy bacteria populations as they grow up.

At the same time, researchers want their findings to soon help physicians treating patients suffering from various diseases, or even combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

"We're really trying to move fast, to make sure that the findings of this study translate research into clinical applications," Segre noted.

Some future solutions could arise from the more holistic understanding of the body's ecosystem, and especially as researchers begin to understand how modern medicine has altered the balance already.

"I would love to know what grew on our skin before antibiotics," Segre said.

- Video: Flu Myths and Truths

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- The Invisible World: All About Microbes

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus