Human Gut Loaded with More Bacteria Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

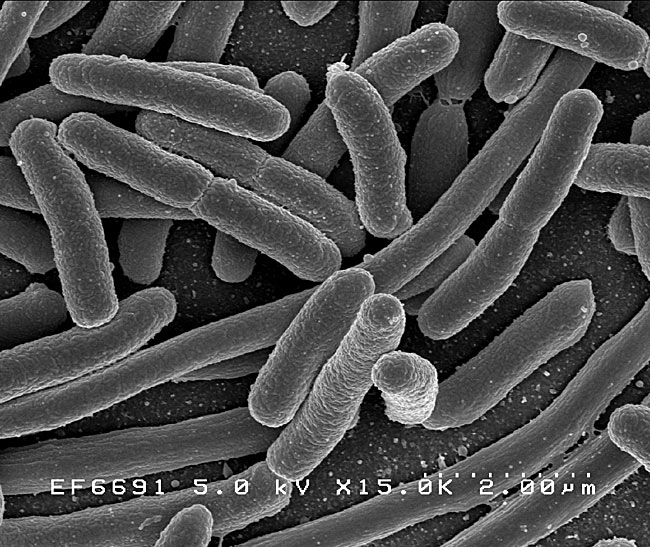

Your gut is the tropical rainforest of your body, at least in terms of bacterial diversity.

A new study, detailed online Nov. 18 in the journal Public Library of Science-Biology, found that the bacterial community in the human bowel is 10 times more diverse than previously thought.

In sheer numbers, the mammalian colon harbors one of the densest microbial communities found on Earth. For every human cell in your body, there are roughly 10 single-celled microbes, most of which live in your digestive tract.

Previous estimates of the number of distinct kinds of microbes in the human colon ranged upwards of 500. These older estimates were made by growing the bacteria that dwelled in the lower gut in a Petri dish, but this method often left rarer species out of the count, only capturing their more common brethren.

David Relman of the Stanford University School of Medicine and his colleagues used a technique known as pyrosequencing to get a more complete count of the different varieties of bacteria colonizing the human colon.

Pyrosequencing has been used before to assess the richness of bacterial ecosystems in marine environments and soil, Relman said. "But this was one of the first times it has been employed to look inward at the ecosystems within our own bodies," he added.

Pyrosequencing generates extremely large numbers of small DNA "tags" copied from the genes of organisms being examined. Species can be sorted out from each other by looking at variations in DNA sequences that code for a molecule universal among all living cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The new gene-sequencing technology lets us check far more 'bacterial ID cards' than the older methods did," said Les Dethlefsen, a postdoctoral researcher in the Relman laboratory and the primary author of the study.

The new study found that the bacteria community of the colon was even more diverse than ever imagined, turning up at least 5,600 separate species or strains. The work was funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Trust, National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation.

While intestinal microbes by and large mind their own business, feeding off the food we send to our stomachs, they also perform critical functions, such as fine-tuning our immune systems and producing nutrients such as vitamin K. And just by occupying intestinal real estate and eating up our waste, they prevent pathogens from gaining a foothold.

Taking antibiotics can reduce the number and diversity of the resident bacterial population. Many scientists worry about the large-scale effects of over-prescribing antibiotics, particularly the potential to create more antibiotic-resistant strains of harmful bacteria. Relman and Dethlefsen hope that pyrosequencing will help better suss out the effects of antibiotics on beneficial bacteria and their human hosts.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus