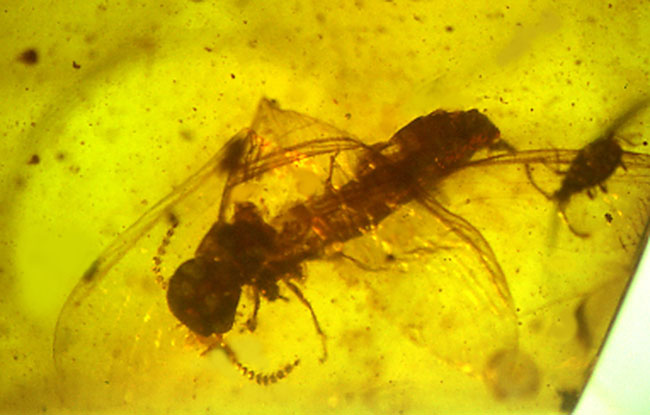

Ancient Termite Spilled Its Guts in Amber

One hundred million years ago a termite was wounded and its abdomen split open. The resin of a pine tree slowly enveloped its body and the contents of its gut. In what is now the Hukawng Valley in Myanmar, the resin fossilized and was buried until it was chipped out of an amber mine. The resin had seeped into the termite's wound and preserved even the microscopic organisms in its gut. These microbes are the forebears of the microbes that live in the guts of today's termites and help them digest wood. The fossil is the earliest example of a relationship between an animal and the microbes in its gut, a new study shows. "The chances of finding a termite with its body open like this are rare," said George Poinar, an amber expert at Oregon State University who led the research, published in the latest edition of the journal Parasites and Vectors. The amber preserved the microbes with exquisite detail, including internal features like the nuclei. "In some of these [microbes] you can actually see wood particles," Poinar told LiveScience. Wood is the termite's diet, a fact that makes the insects the bane of homeowners and a boon to exterminators. The insect could not digest the sugars in wood, called cellulose, without the aid of a separate kind of animal in its gut: several kinds of protozoa. The termite chews off pieces of wood and swallows them in mouthfuls that the protozoa can break down. Then the termite digests the leftovers. Without the protozoa, the termite would starve. Meanwhile, the protozoa would quickly die outside of the termite, resulting in a relationship of dependence between the animals that scientists call "mutualism." Since termites and their protozoa are separate animals, each new generation of termite must be united with its microscopic crew of wood digesters. To do so, adult termites secrete a liquid from their anus that is laced with protozoa and newly hatched termites lap it up. Termites are related to cockroaches and split from them in evolutionary time at about the same time the termite in the amber was trapped. "Lo and behold the DNA evidence that came out said that basically all termites were cockroaches," said Vernard Lewis, termite expert at the University of California at Berkeley, who was not involved in the amber study. Roaches today also have gut microbes, and the common ancestors of both insects probably did, too, Lewis said. Those in the termite gut give it a distinct advantage. To describe it, Lewis pictures an ancient rainforest floor covered with decaying plants. "Think of a roach running around in there probably 10 stories deep in leaf debris and ferns," he said. "Wouldn’t it be a slick trick if you could somehow use microbes to make use of that leaf litter?" Their internal passengers allow termites to digest more of what they eat and become efficient and evolutionarily successful. Numbering about 2,300 known species, termites today are widespread, though more common in tropical climates. "Books, wood, living plants – it's amazing what termites can feed on," Poinar said. In forests they perform the important work of breaking down and recycling dead wood and improving the fertility of soil. We think of them now as pests because they don’t distinguish between wooden planks in walls and fallen logs on the forest floor. "As far as they’re concerned wood is wood," Poinar said.

- Secret Insect Weapons

- Implants Create Insect Cyborgs

- All About Insects

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.