Photos: 305-Million-Year-Old Arachnid Trapped in Rock

Almost a spider

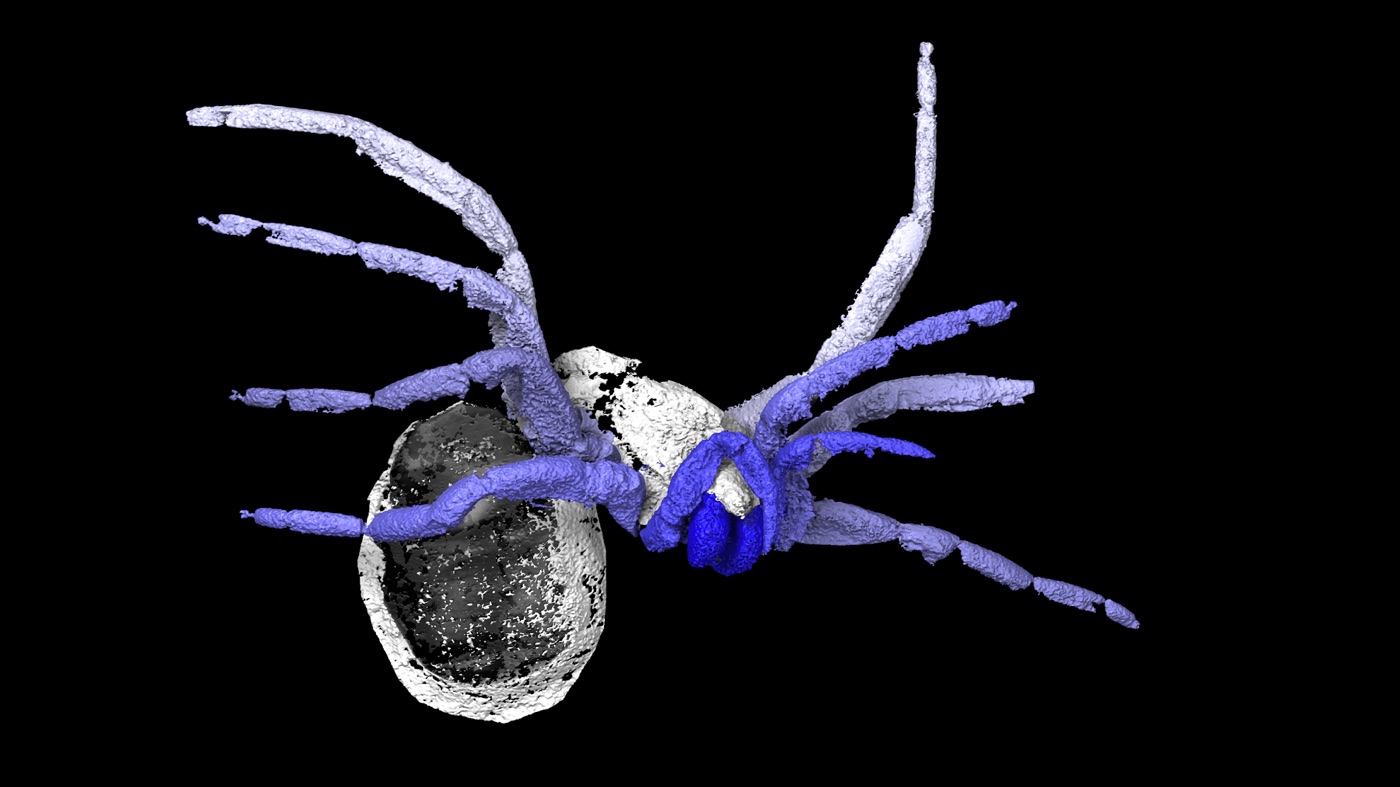

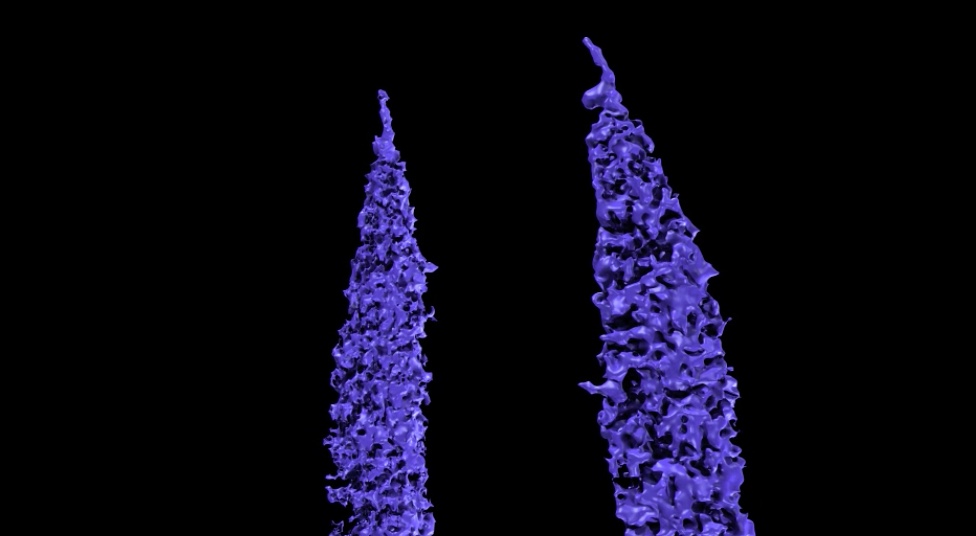

A computed tomography (CT) image of a 305 million-year-old arachnid that is almost, but not quite, a spider. This arachnid lived alongside true spiders in what is now France, but did not have the silk-spinning spinnerets that define spiders.

Researchers reported the discovery of this new arachnid, Idmonarachne brasierii, on Wednesday, March 30 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The fossil was discovered decades ago, but because its front half was buried in rock, researchers did not unlock its secrets until they used a CT scanner to peer inside. [Read the full story on the "almost spider"]

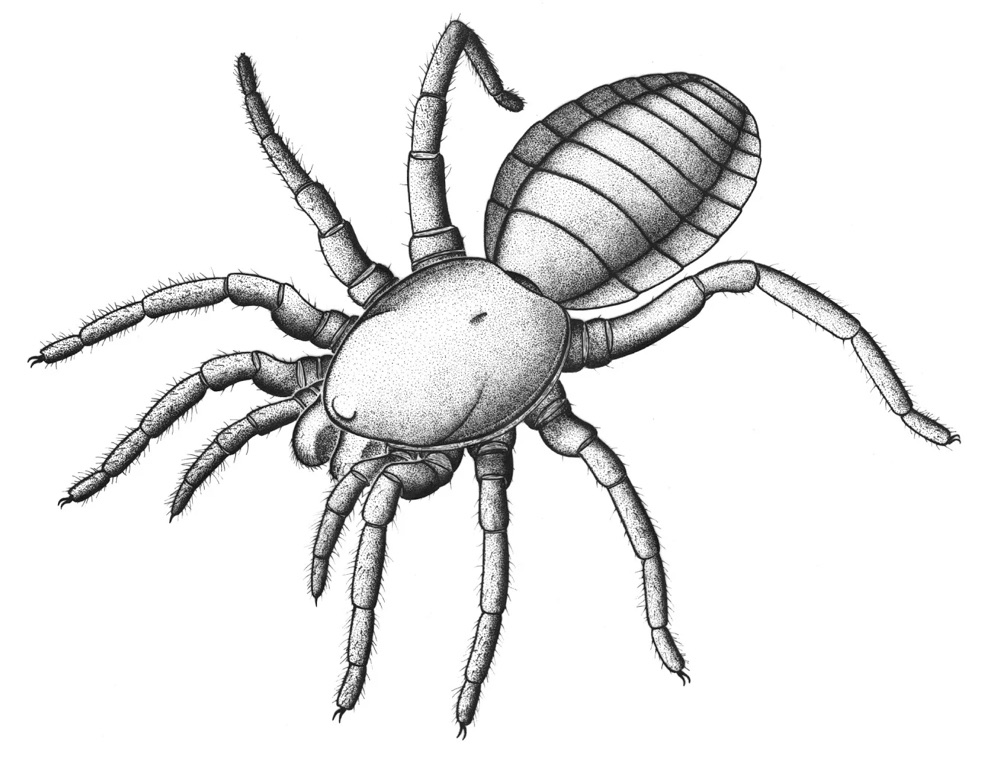

Arachnid ancestor

Idmonarachne brasierii, the 305 million-year-old spider relative, has spiderlike mouthparts and legs. But its abdomen is segmented, unlike modern spiders', and it lacks spinnerets. This spider lived alongside some of the oldest known true spiders, but none of its descendants are alive today. Spinnerets may have been the adaptation that made true spider so successful and diverse, study researcher Russell Garwood of the University of Manchester told Live Science.

Myth and legend

Idmonarachne brasieri gets its name from Idmon, the father of Arachne, who in Greek myth was turned into a spider by the goddess Athena. The species name is in honor of Martin Brasier, a paleobiologist at the University of Oxford who died in 2014. Here, a computed tomography image of the "almost spider."

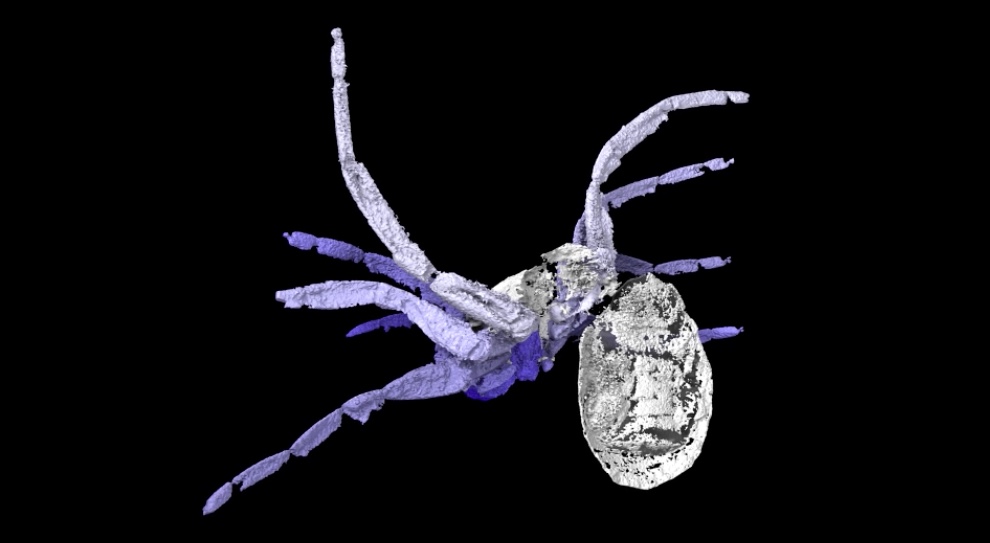

Scanning an Almost-Spider

A side view of I. brasieri, which was found fossilized in iron carbonate in the Montceau-les-Mines in France. The arachnid is about 0.4 inches (10 millimeters) long. Arachnids are the most diverse group of animals after insects, according to study researcher Russell Garwood, but little is known about their origins and relationships. They were among the first terrestrial organisms, adopting a land-based lifestyle at least 420 million years ago. Few terrestrial rocks from that era are preserved, making early arachnid fossils rare.

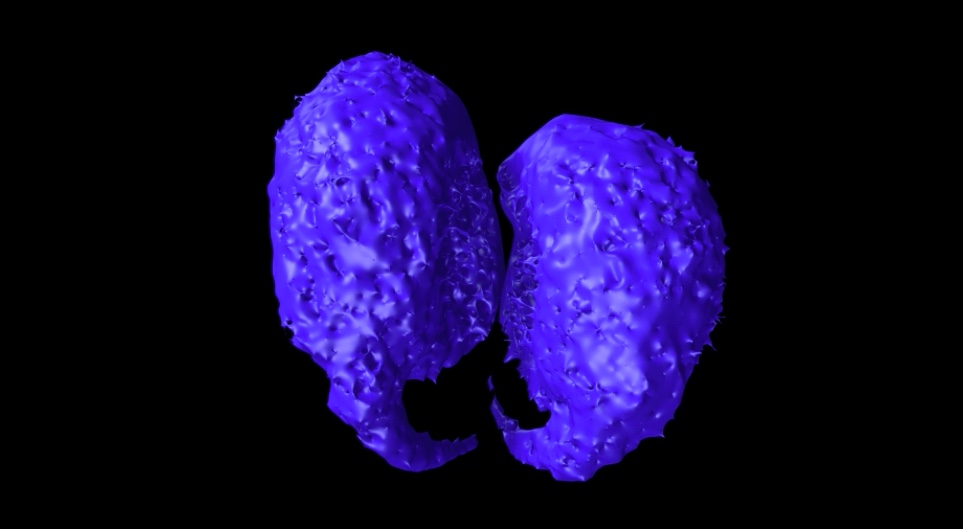

My, What Sharp Fangs You Have

A computed tomography image of the fangs of 305 million-year-old Idmonarachne brasierii. Arachnid species can be differentiated by their mouthparts, and it took a CT scan to see the details of the fossilized fangs of this ancient spider relative. The fangs are very spiderlike, researchers reported March 30 , 2016, in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Arachnid 'arms'

The pedipalps of Idmonarachne brasierii. These appendages look like an extra pair of legs alongside the arachnid's head, but they were used more like arms. These pedipalps are very spiderlike, positioning this arachnid close to spiders in the arachnid family tree. But the absence of spinnerets and a segmented abdomen mark this arachnid as not quite a spider.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

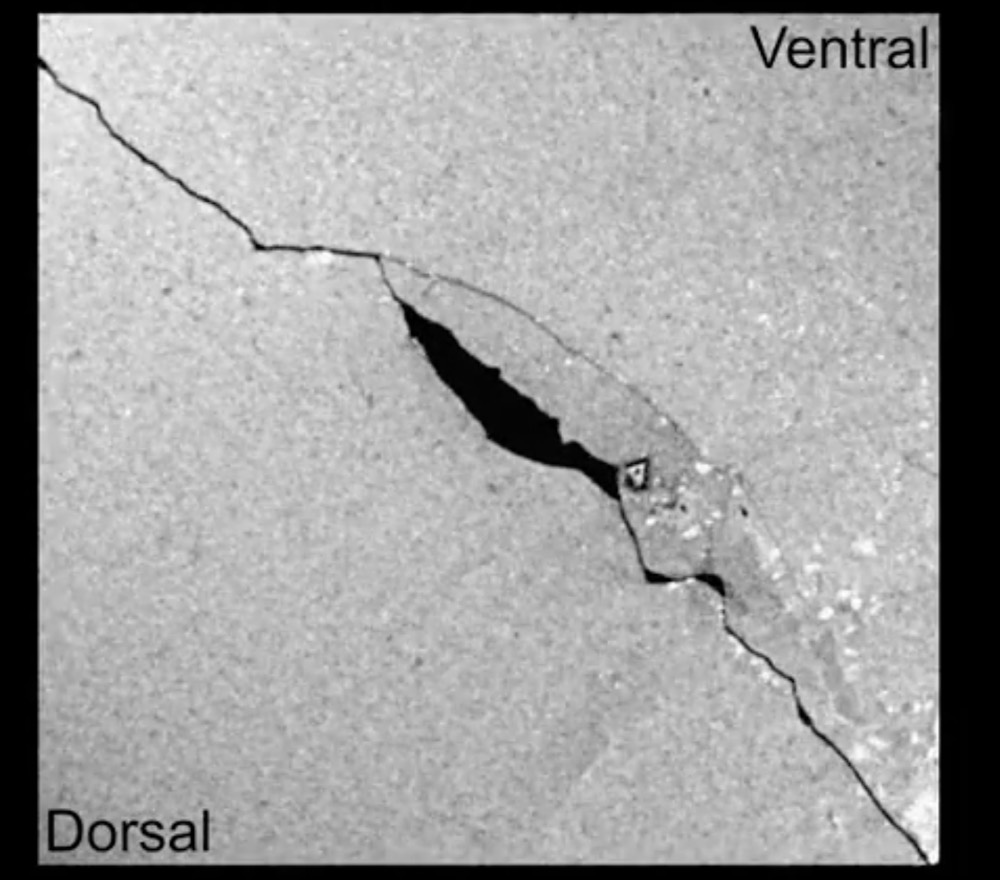

Almost Spider - 7

This image shows a "slice" of the I. brasieri fossil in cross-section. Soon after the arachnid died, the mineral iron carbonate precipitated out around it. The arachnid corpse rotted away, leaving behind a three-dimensional void, seen in black.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.