Jaw-Dropping: Extinct Sea Bear Chowed Down Like a Saber-Toothed Cat

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A mysterious, carnivorous marine mammal that lived 23 million years ago clamped down on its mussel dinner similar to the way a saber-toothed tiger grasped its larger prey, scientists have found.

Peculiar Kolponomos (kol-poh-NO-mos), known from only four skulls found in the Pacific Northwest, was originally thought to be a raccoon relative after it was discovered in 1960. Features from more complete fossils found decades later led experts to link Kolponomos to bears. However, its mollusk diet most resembled that of otters — a finding that paleontologists deduced from the skulls' tooth structure and wear patterns.

But when researchers looked more closely at how Kolponomos may have dislodged its hard-shelled mollusk meals from the sea bottom, they discovered an unexpected resemblance to the bite of a fellow carnivore — Smilodon, the saber-toothed cat, which appeared millions of years later. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

"Weird carnivore"

According to Z. Jack Tseng, a co-author of the study describing the findings, when the researchers' analysis of Kolponomos began, they thought the oddball species would be just another "weird carnivore" entry into an in-progress and fast-growing data set of all living and extinct carnivores.

Tseng, a paleontologist who studies bite-force biomechanics in extinct carnivores at the American Museum of Natural History, is no stranger to peculiar-jawed animals. He had just completed a Smilodon study, he told Live Science, and it occurred to him when he first inspectedKolponomos that there were odd similarities between the skull structure in the saber-toothed cat and that of the lesser-known shell-crushing bear.

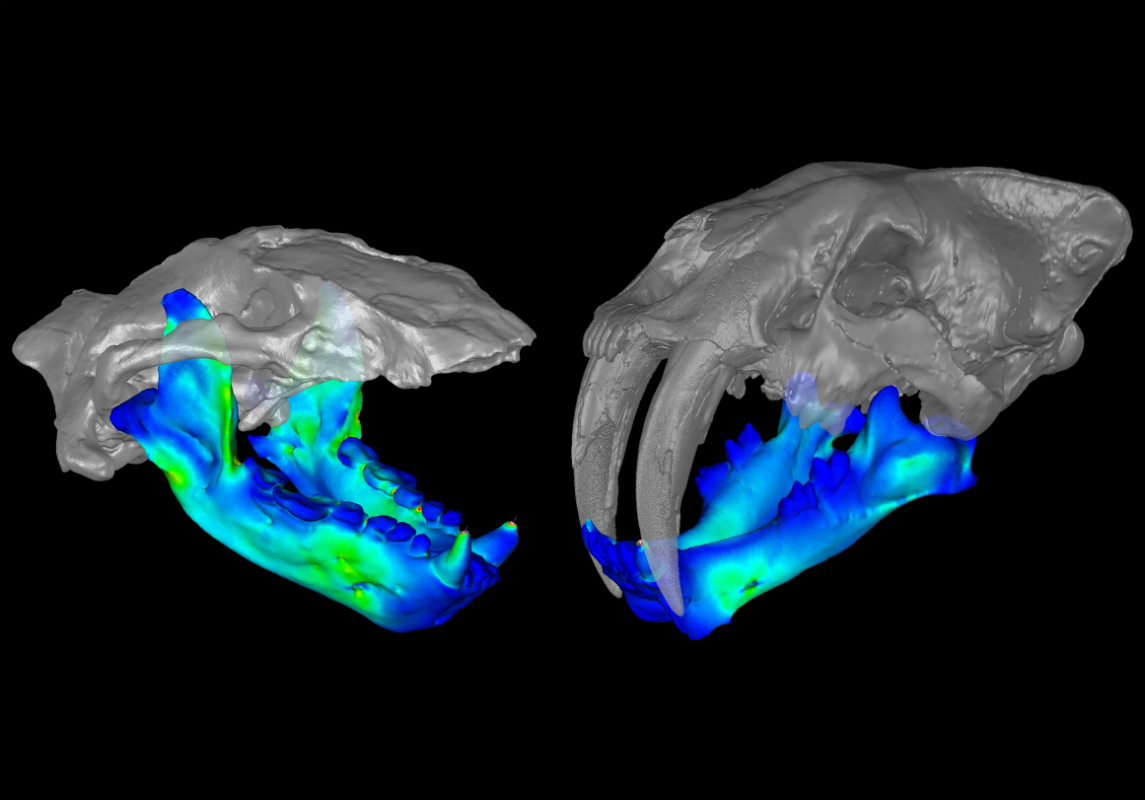

"Kolponomos had no saber teeth, but other parts of the skull — especially the back of the skull where the neck muscles attached — looked very similar to the saber-tooth [cat]," Tseng said. He also noted parallels in the two animals' jaws, which thinned toward the back where they met the skull. This led him to wonder — even though the two species clearly had different diets, could they have used their jaws in the same way?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The lower jaw in saber-toothed cats has been hypothesized to serve as an anchor to fix the head against the prey, allowing a stable point around which to swing the sabers," Tseng said. "For Kolponomos, the lower jaw would serve the same purpose, of anchoring the head to one side of the shell, and then closing the mouth and using the very powerful neck muscles to twist and get the prey off of the rock."

Reconstructing an extinct animal's bite

To find out, Tseng turned to digital methods that are still fairly new for biologists and paleontologists, but are commonly used by engineers and architects to test the stresses in buildings and bridges. "It's the same idea, but applied to biological structures," Tseng told Live Science.

They scanned the skulls with a method called computed X-ray tomography, producing images of internal and external skull structures, which the researchers used to create 3D computer models. Once they had the models, the researchers' ran bite simulations and compared skull strength and stiffness aligned with forces like muscles and bite points.

Tseng explained that they modeled and simulated not only Kolponomos and Smilodon skulls but also the skulls of other species that were closely related to them. "What we found was that, in efficiency and in skull stiffness, Kolponomos and Smilodon were most similar to each other, and not to their closest relatives," Tseng said. "There's a connection between how they look and how they work structurally."

It may seem odd that an animal with a diet like a sea otter's would have a feeding strategy like a saber-toothed cat's, but Tseng suggested that Kolponomos' and otters' bodies may have differed dramatically in ways that caused their eating habits to diverge. However, without skeleton fossils for Kolponomos, it's difficult to say for sure, Tseng said.

"Sea otters smash shells with rocks, and using tools removes the selective pressure to have really strong jaws," Tseng said. "We'll find out more if somebody were to discover forelimbs of Kolponomos, but based on its biomechanics, it would have made sense that Kolponomos is more reliant on its mouth."

For anyone who's curious enough to compare Kolponomos and Smilodon skulls for themselves, the study authors have made their models available to download and 3D print.

The findings were published online today (March 1) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus