Scientists Isolate Antibodies That Fight Ebola

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

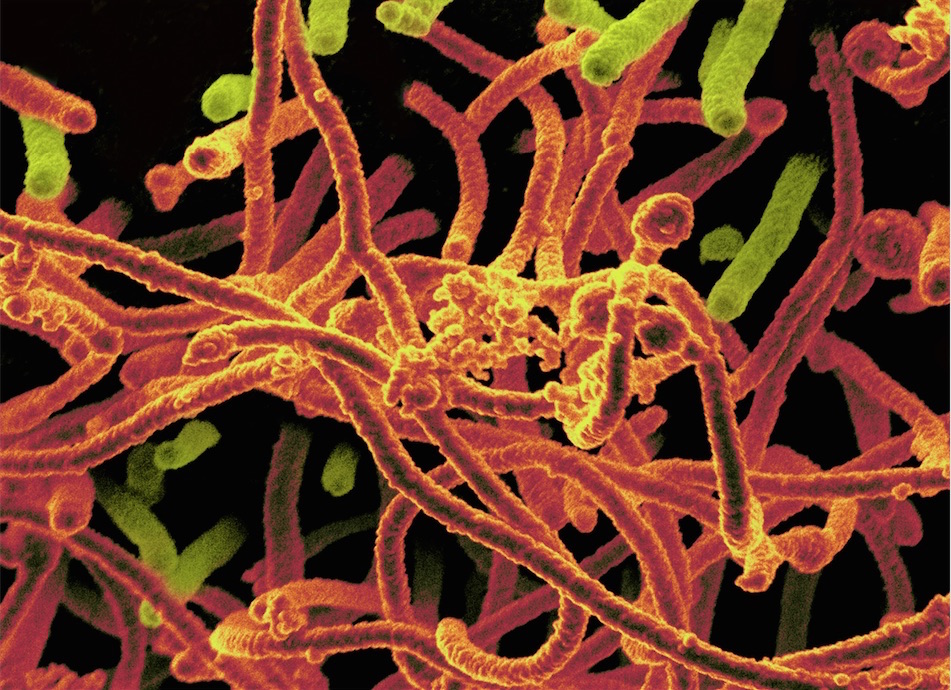

An Ebola survivor's blood and a new technique for isolating immune cells may have opened up new ways to combat the deadly virus.

In a new study, researchers took antibodies from an Ebola patient who showed a particularly strong immune response against the virus, isolated the groups of antibodies that they suspected would be the most effective in fighting the virus, and then used these antibodies to treat mice that were infected with the virus.

"What we were trying to do was understand the antibody response in survivors," said Laura Walker, a co-author of the study and a senior scientist at Adimab, a biopharmaceutical company in Lebanon, New Hampshire, which funded the study. "When you put [the antibodies] into mice, it prevents the virus from infecting cells."

The researchers hope the information can be used to design vaccines or treatments for Ebola. [Where Did Ebola Come From?]

"You can use those antibodies as a template," she said. "One can imagine designing a vaccine" based on these antibodies, she said. (No vaccine has yet been designed using isolated antibodies in this way.)

Immune systems in both mice and humans fight viral infections by generating antibodies against viruses that enter the body. Antibodies, for example, may latch onto the outside of a virus, preventing it from attaching to target cells. Antibodies also flag invading viruses as invaders, signaling immune system cells to engulf them.

However, the antibodies in the blood are specific to certain viruses: A given antibody may work to fight one virus, or perhaps several closely related viruses, but not all viruses. To find out which antibodies in a person might be working against a certain virus, researchers isolate them from the blood, and see which ones stick to the virus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But picking out certain antibodies is a difficult thing to do. So the group at Adimab devised a new technique to find them. The researchers isolated the cells that make antibodies, called B cells, while they were producing the antibodies.

By isolating individual B cells, the scientists could also figure out exactly which part of the Ebola virus each antibody sticks to, as each antibody may latch onto a different part of Ebola's outer protein "coat."

Isolating the cells made the needle-in-a-haystack task of finding the desired antibodies a lot easier, Walker said. The team identified 349 antibodies made by the patient's B cells, and but only about 10 worked well against Ebola, Walker told Live Science.

After isolating these antibodies, the Adimab scientists teamed up with researchers at several other laboratories to see how well each antibody worked on mice infected with Ebola.

They found that the mice injected with certain antibodies had a 100 percent survival rate, whereas others had much lower survival rates. The findings should be confirmed with more experiments, Walker noted.

But the isolation of the antibodies may be why this treatment worked better than earlier experiments that involved treating people infected with Ebola using blood plasma (which contains antibodies) from people who had survived the disease. Other researchers have shown that this so-called "convalescent plasma" approach does not improve survival rates.

"When you use blood serum, it's all mixed together," Walker said. In other words, it isn't clear that the antibodies that are best for fighting Ebola were present in the plasma given to the sick people, but even if they were, they were diluted with others.

Johan van Griensven, an infectious disease researcher at the Institute for Tropical Medicine in Belgium, said that the isolation of the antibodies in the new findings will be helpful to researchers looking for ways to fight Ebola.

The reason doctors tried using blood plasma from survivors to treat Ebola patients was that they needed to act quickly, and so they weren't able to take time to isolate specific antibodies, said van Griensven, who was not involved in the new findings, but has researched the plasma approach. He noted that it remains to be seen whether the new findings will hold up in tests in humans.

Miles Carroll, a public health researcher with the U.K. government who has extensively studied Ebola, said the big benefit of the new study may be in finding more-effective cocktails of antibodies for treatments.

There are Ebola vaccines already being tested in human trials, as well as an antibody-based Ebola treatment called ZMapp, Carroll said. But the new study has found some specific parts of Ebola's protein "coat" that researchers could target with antibodies, to more effectively fight the virus, he said.

Walker agreed that there's a long way to go before human trials. Adimab published its data to give other researchers a starting point, she said. "It demonstrates the technology for future infectious diseases," she said.

The study was published Thursday (Feb. 18) in the journal Science.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus