An American doctor working in West Africa and another health care worker, also American, who contracted Ebola there have both received experimental treatments for the deadly viral disease, according to news reports.

Nancy Writebol, a worker with the charity Samaritan's Purse, received an experimental serum, and Dr. Kent Brantly, from the same charity, received a blood transfusion from a patient who recovered from Ebola, according to NBC News. One or both of the health care workers are also being flown to an isolation unit in an American hospital for treatment, according to news reports.

Though there are conflicting reports, and no one is saying exactly what the experimental serum is, its likely that both of the reported methods contained antibodies to the Ebola virus, said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Delivering antibodies to a patient could slow the virus's replication, and give the immune system time to recover.

"There is a long tradition of using immune serum as treatment," Schaffner told Live Science. "You give the person antibodies, and you would hope that those antibodies would then bind the viruses and interfere with their multiplication."

No current treatments

This Ebola outbreak is the largest in history, and has so far claimed 729 lives in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. Doctors without Borders has said that the crisis is "out of control." Sierra Leone has declared a national emergency, closed all of its schools and is quarantining disease hot spots. [2014 Ebola Outbreak (Infographic )]

There are no treatments or vaccines available for Ebola, though several are in the pipeline. A study in Nature this year reported that one drug improved survival in monkeys who were exposed to a closely related virus, called Marburg virus. Public Health Canada is testing another antibody-based treatment, and the company Tekmira Pharmaceuticals has developed an experimental drug that uses a process called RNA interference to block the virus' replication, Forbes reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Antibody methods

As for the American health care workers, one possibility is that Writebol was given a concentrated form of antibodies to the virus from someone who survived, Schaffner said. To make such a treatment, researchers would have to separate and concentrate the antibodies from a survivor's blood.

If Writebol did receive such an immune serum, it would almost certainly have to have been created at the site of the outbreak, and have come from someone infected with the same strain of Ebola that she has, said Thomas Geisbert, a virologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, who has helped develop potential Ebola drugs.(There are several species of Ebola virus; the current outbreak is caused by one called the Zaire species.)

Brantly is reportedly receiving a transfusion of whole blood from a 14-year-old patient who survived the disease.

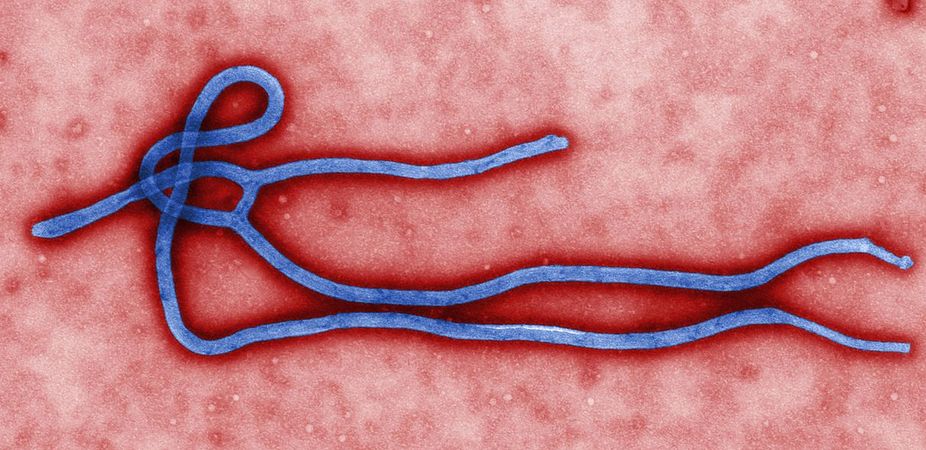

In an Ebola infection, the virus first disables some of the immune system's frontline cells, and then replicates almost unchecked. It then bursts out of cells throughout the body and damages them, eventually causing multi-organ failure.

Both experimental treatments, if they work, would need to lower the viral load by binding to the virus and preventing it from replicating, which would give the immune system enough time to regenerate its cells and fight the disease, Geisbert said.

However, such treatments likely have limitations. In the last stages of the disease, in a process known as a cytokine storm, the immune system goes haywire and inflammatory molecules called cytokines attack the body's own tissue.

At that point, "if you're 24 to 72 hours from death and you've got a full blown case of Ebola hemorrhagic fever, there's probably nothing on the planet that's going to save you," Geisbert told Live Science.

Will it work?

It's not clear that using antibodies from recovering patients would work. In a 1995 outbreak, eight patients were given serum from recovering patients and only one died, according to a 1999 study in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. However, those patients may have been given the drug when they were already on the road to recovery, Geisbert said.

When Geisbert and his colleagues tested a treatment made from human antibodies in monkeys injected with Ebola, the antibodies failed to protect rhesus macaques from infection and death, according to a 2007 study in PLOS Pathogens.

However, a cocktail of engineered Ebola antibodies called MB-003 developed by Mapp Biopharmaceuticals seemed to protect monkeys exposed to the virus, a 2013 study in Science reported. In animal models, some of the newer antibody treatments seem to be more effective at combating the disease, perhaps because they are more targeted, Geisbert said.

Measuring effects

In the current outbreak, about 40 percent of victims have survived even without treatments, making it hard to gauge any treatment's effectiveness, Geisbert said.

To assess if a treatment was helping, doctors would need to measure the amount of virus in multiple patients' blood and bodily fluids before treatment, and then frequently afterwards. If the treatment worked, they would expect to see a steep drop in the number of virus particles circulating in the body soon after injection, not a gradual decay, Schaffner said.

But even then, it would be hard to say whether a treatment worked, Geisbert said.

"My fear is that they're going to give it to somebody that's almost ready to die and then blame the treatment, and I don't think that's fair," Geisbert said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.