Ancient Stubby-Legged Reptiles with Tiny Heads Were World Travelers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

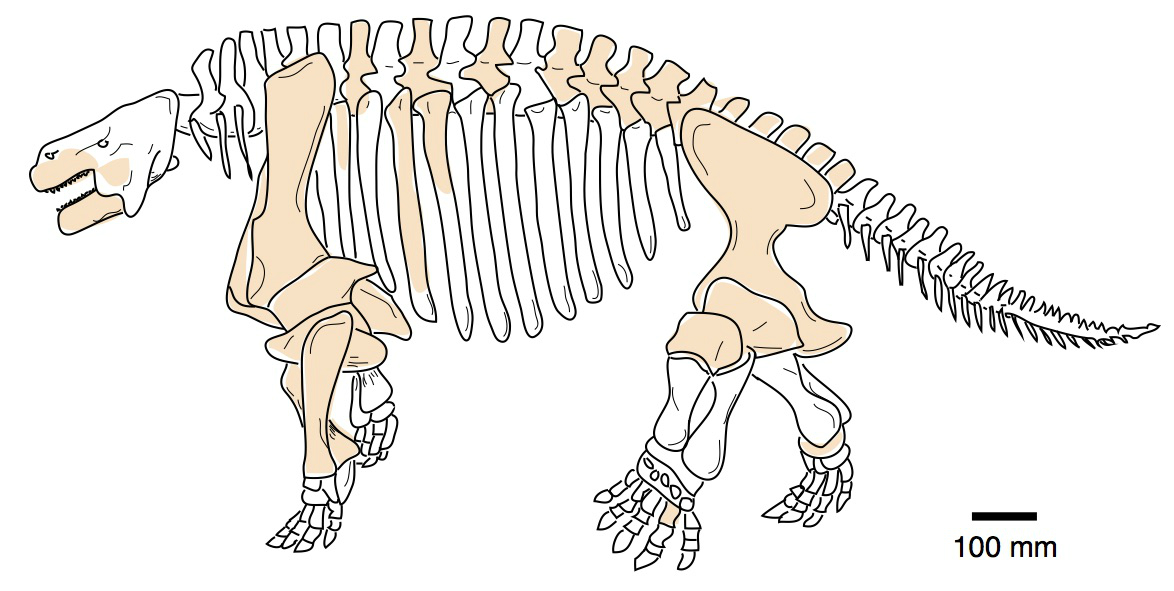

Before dinosaurs roamed the planet, tanklike herbivores called pareiasaurs — barrel-chested and stubby-legged turtle relatives — reigned as Earth's first large plant-eaters. With tiny heads and bony knobs studding their skulls and bodies, pareiasaurs wouldn't have won many beauty contests. But their stumpy legs did succeed at carrying them far and wide on land, a new study found.

Pareiasaurs lived during the Permian era, about 266 million to 252 million years ago. They were built low to the ground, with wide, sprawling bodies that measured about 7 to 10 feet (2 to 3 meters) long and were covered with a bony armor plating that likely protected them from sharp-toothed predators. Compared to the dinosaurs' tenure on Earth, pareiasaurs' time was relatively brief, terminating after only 10 million years, during the Permian mass extinction.

They are best-known from specimens discovered in abundant fossil deposits in South Africa and Russia — at the Russian site, pareiasaurs represented 52 percent of the fossils from tetrapods (animals with four limbs). Other isolated finds have also emerged in Europe, South America and China. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

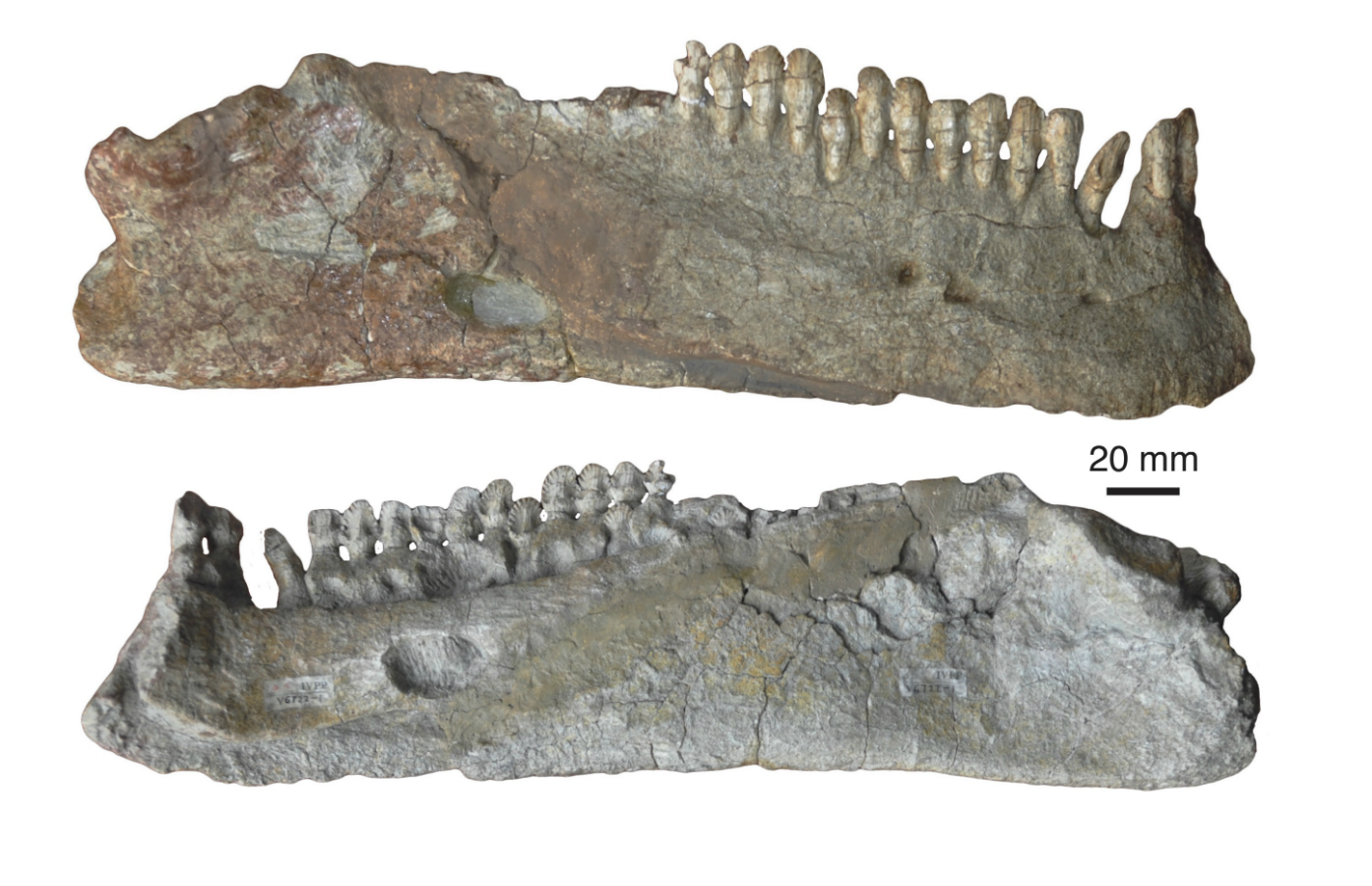

The Chinese specimens, which were thought to represent six species, were recently analyzed in detail for the first time. Scientists determined that they were actually only three distinct pareiasaur species, and that they were "closely related" to other pareiasaur species in Russia and South Africa, according to study author Mike Benton, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Bristol.

The finding suggests that these lumbering and likely slow-moving reptiles were also capable of wandering great distances, he said in a statement.

"We see the same sequence of two or three forms worldwide," Benton said, pointing out that geologic evidence from the era suggests that there would have been no barriers preventing pareiasaurs from traveling to regions that are separated from each other today. "They could walk all over the world," he added.

The findings were published online Feb. 19 in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus