Jimmy Carter Gets New Melanoma Treatment: Here's How It Works

To treat Jimmy Carter's cancer, doctors will use one of the newest advances in cancer therapy — a class of drugs that mobilizes a patient's own immune system against their cancer.

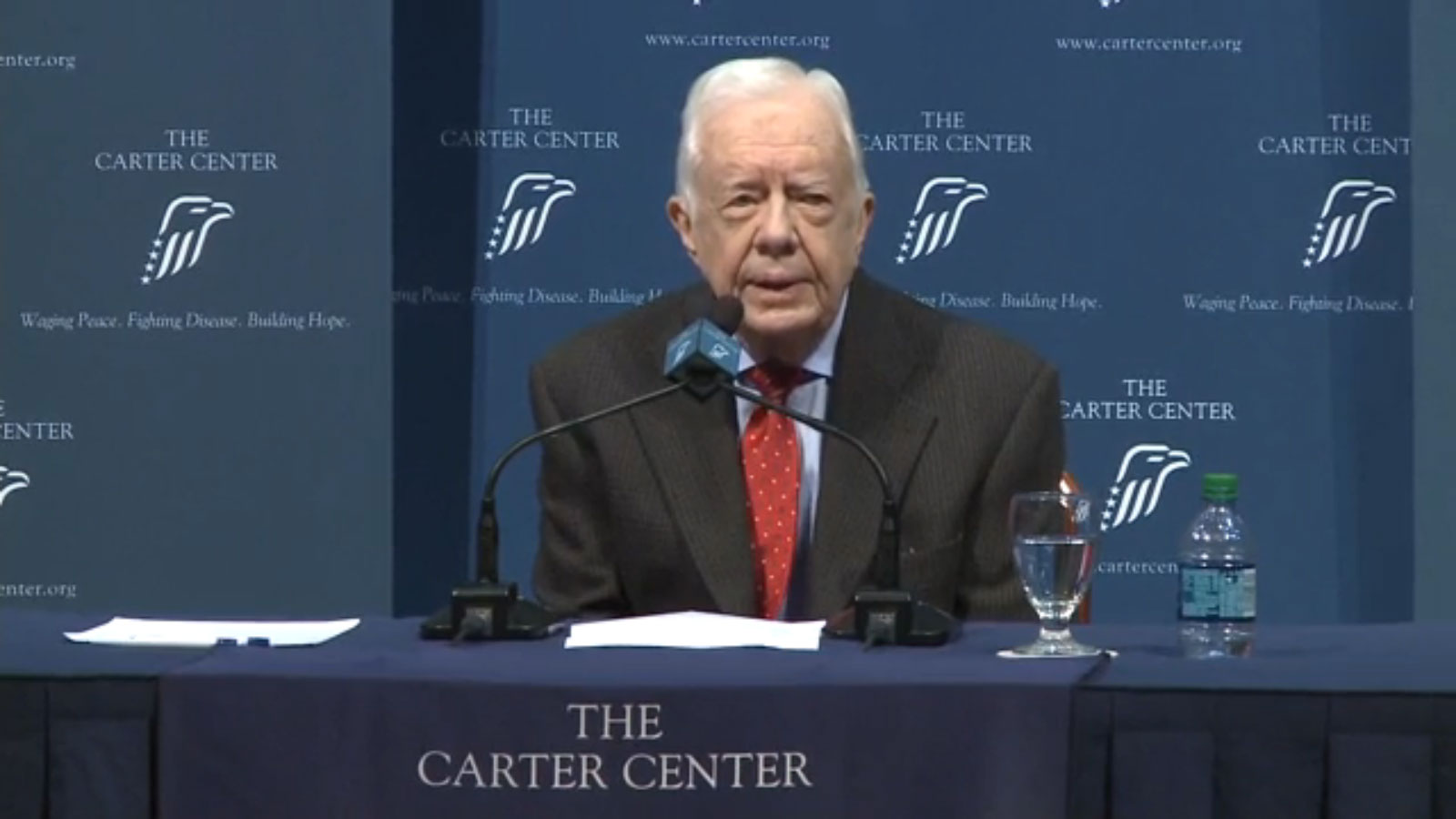

On Thursday (Aug. 20), the former president announced that he has advanced melanoma, a type of skin cancer, and that it has spread to his liver and brain. Doctors have already removed a small tumor from his liver, and he will start a course of radiation therapy to treat the tumors in his brain, Carter said at a news conference. (The radiation therapy is known as stereotactic radiation, which allows doctors to better direct radiation beams at each specific tumor.)

But Carter also said he has received a drug called pembrolizumab (sold under the brand name Keytruda), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last year to treat metastatic melanoma. The drug is a type of immunotherapy, a treatment that helps the immune system fight cancer.

Recent advances in immunotherapy have changed the way metastatic melanoma is treated, said Dr. Grace Dy, an associate professor of oncology at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, who is not involved in Carter's treatment. Doctors used to treat patients with metastatic melanoma chemotherapy, even though few responded to the treatment.

"Ten years ago, 20 years ago, all that we had were chemotherapy [drugs], but we knew it didn't work very well" for people with metastatic melanoma, Dy said. "Now with better drugs, we hardly use chemotherapy anymore" for these patients, Dy said. [10 Do's and Don'ts to Reduce Your Risk of Cancer]

Dr. Antoni Ribas, director of the University of California, Los Angeles' Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center Tumor Immunology Program, agreed. "There's been a lot of progress in [metastatic melanoma] treatment recently with the advent of immunotherapy," Ribas said.

A recent study by Ribas and colleagues found that about one-third of melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab responded to the drug, meaning that these patients experience a meaningful decrease in their tumor size.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some melanoma patients who took the drug lived a few years after their diagnosis, Ribas said. Before the availability of these newer immunotherapy treatments, the average survival time for someone with metastatic melanoma was around 6 to 10 months, Dy said. Now, survival times with the newer drugs can be double, or, in some cases, triple, what they used to be, she said.

Ribas noted that it's not clear how well this drug works for people with melanoma that has spread to the brain. But even if the drug does not shrink the tumor, it may prevent it from growing further, Dy said.

In general, pembrolizumab works by "unleashing an immune response" against the cancer cells, Ribas said. Melanoma can "hide" from the immune system by expressing a protein called PD-1, which turns off the immune response. But pembrolizumab targets PD-1, which allows the immune system to attack the cancer. Another immunotherapy drug, called nivolumab, also targets PD-1, and was approved by the FDA in December 2014.

One of the first new immunotherapy drugs for melanoma was ipilimumab, which was approved in 2011. But the side effects of the drug were quite severe, Dy said. In contrast, pembrolizumab and other similar, newer drugs are tolerated better by patients, she said.

Carter also said he will undergo further tests to try to determine where on his body his melanoma started.

However, experts said that because doctors already know what type of cancer Carter has, finding out where it started in the body is not very important for his treatment. "At this point it's not critical," Dy said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.