Melanoma: Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

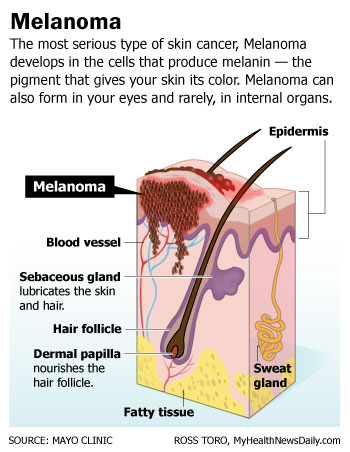

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that begins in the skin's pigment-producing cells, called melanocytes. These cells make melanin, which is responsible for the color in skin, eyes and hair.

The National Cancer Institute said that only 2 percent of all skin cancers are melanoma, so it is very rare. It is also very dangerous. Of all types of skin cancer, melanoma is the deadliest. In 2017, the National Institute of Health (NIH) estimates that there will be 87,110 new cases of melanoma and 9,730 deaths.

While men are usually diagnosed in their 60s, women can get the disease at any age, with risk increasing based on family history and amount of sun exposure. Melanoma is one of the highest cancer killers of women in their mid-20s to mid-30s, said Doris Day, a dermatologist in New York City and an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital, also in New York.

"Melanoma is the least common, but most serious of all the skin cancers," Day told Live Science. Basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers occur more often than melanoma, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation.

Causes & risk factors

Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays from sunlight is a leading cause behind melanoma. When sunlight hits melanocytes, they make more of the pigment melanin, darkening the skin. This can result in a tan, freckles or moles — the vast majority of which are benign.

Researchers think that enough UV radiation exposure can damage the DNA in melanocytes, causing them to grow out of control into a tumor. Blistering sunburns in childhood, use of tanning beds and any excessive exposure to UV radiation increases the risk for melanoma, according to the Mayo Clinic.

A melanoma tumor often originates in an existing mole or starts as its own lesion that looks like a mole. People with more than 50 ordinary moles are more likely to develop melanoma, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Melanoma also strikes fair-skinned people more often. Having less pigment in your skin means you have less protection from UV radiation. Caucasians are 30 times more likely to develop invasive melanoma than people of African descent, according to the National Cancer Society.

Melanoma tumors most often occur in areas of the body that are exposed to direct sunlight such as the arms, legs, head and face, according to the Mayo Clinic. Yet, melanoma can form anywhere on the body where there is melanin, including the eyes and the small intestines, according to the National Cancer Institute.

"I had somebody who had it in the bellybutton, and that's not somewhere that gets a lot of sun exposure," Day said. "It can occur anywhere in your body."

One type of melanoma, called acral lentiginous melanoma, may appear as a black or brown discoloration on the soles of the feet, under the nails or on the palms of the hand.

Since melanoma can occur in areas of the body with little to no sun exposure, doctors believe a combination of genetic and environmental factors — including UV exposure — may lead to melanoma, according to the Mayo Clinic.

People with a family history of melanoma are more likely to develop the cancer. One in 10 people diagnosed with melanoma have a family member who was also diagnosed with the disease, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Symptoms & diagnosis

The first signs of melanoma appear as an unusual mole or as changes to an existing mole.

A mole that is asymmetric in shape, has a ragged border, has uneven coloration, is larger than the diameter of a pencil eraser and has changed in appearance may be a sign of melanoma.

An easy way to remember what changes to look for in moles is to refer to your ABCs: A is for asymmetry, B is for border, C is for color, D is for diameter and E is for evolving, Day said.

A mole that bleeds or itches is also a warning sign for melanoma.

Trained dermatologists can perform head-to-toe screenings to find any irregular moles. However, the only way to diagnose melanoma is with a biopsy, according to the Mayo Clinic.

A MelaFind scanner, a technology developed in conjunction with NASA, can also help doctors examine suspect moles. The researchers who developed MelaFind scanned and biopsied more than 10,000 brown marks, and developed an algorithm that gives information about the lesion, Day said.

The scan, which costs about $175 out of pocket for an examination of several spots, can look 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) down into the skin, and doesn't require cutting, Day said.

If the scan finds the spot may be cancerous, doctors will biopsy the area and send it to a lab, where researchers "look at the pattern of cells and how quickly they're dividing, and then they give us a report," Day said.

Treatment

Melanoma often has good prognosis when the cancer is caught early. If the lesion has not spread beyond the surface of the skin, simple surgery may be enough to cure cancer.

"If it's less than 1 millimeter [0.04 inches], then we just cut it out with a good margin," Day said.

The National Cancer Institute estimates people diagnosed with localized melanoma have a five-year survival rate of 91.7 percent. Luckily, 84 percent of melanoma cases are diagnosed at this stage.

However, if melanoma spreads to other parts of the body, it can be difficult to treat, according to the NIH.

If the spot is more than 1 millimeter in depth, doctors may do a sentinel node biopsy, which uses a dye to see if the tumor has spread to the lymph node system. Then, doctors will remove the spot, as well as the dyed lymph nodes, which are then checked for cancer. If the sentinel nodes are cancer-free, then the cancer probably hasn't spread, and doctors won't have to remove more lymph nodes, Day said.

If a person has melanoma, doctors will also check the person's head and chest.

"Every cancer has its place it likes to go," Day said. "Melanoma likes to go to the brain and the lungs, so we get chest X-ray and a brain scan."

If melanoma has spread under the skin to nearby lymph nodes, the five-year survival rate is 62 percent. If it has spread to distant parts of the body, the five-year survival rate is 16 percent.

People whose melanoma has spread beyond their skin may require chemotherapy, radiation or biological therapy to treat the cancer. Traditional chemotherapy doesn't work well for melanoma, but many patients use interferon, a protein that helps the immune system.

"[But] interferon unfortunately was not an ideal treatment because it extends life for 11 months or so in advanced cases, but it was a miserable 11 months," Day said.

Now, doctors can map each person's melanoma to see whether it has a genetic pattern that can be treated with chemotherapy. "And if it does, there are some specific chemo agents that work better, and have a much greater chance of remission and long-term survival with [fewer] side effects," Day said.

Metastatic, or spreading, melanoma used to be a death sentence, but now it's "basically a chronic illness," she said.

The National Cancer Institute has a list of current medications and treatments for melanoma. There are currently many medical trials being performed with possible new treatments for melanoma.

Prevention

Preventing melanoma can be a lifelong task, but it only takes a few simple precautions to reduce the risk.

Avoiding tanning beds is an easy step, as is wearing sunscreen year-round. Choose a sunscreen that has a high SPF rating for the best protection. "Use a sunscreen of at least 30 SPF, even on overcast days," said Dr. Dheeraj Taranath, a regional medical director with MedExpress in Reading, Pennsylvania. Here is some important information on sunscreen. Wearing hats, visors and tightly woven clothing is also a great way to block UV rays.

Finally, staying out of the midday sun — between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. — will protect skin from the sun's radiation when it is strongest.

"Stay out of the sun and get regular skin cancer screenings so that if you find it, you find it early," Day said.

Additional reporting by Alina Bradford, Live Science Contributor.

Additional resources

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus