Ancient Jellies Had Spiny Skeletons, No Tentacles

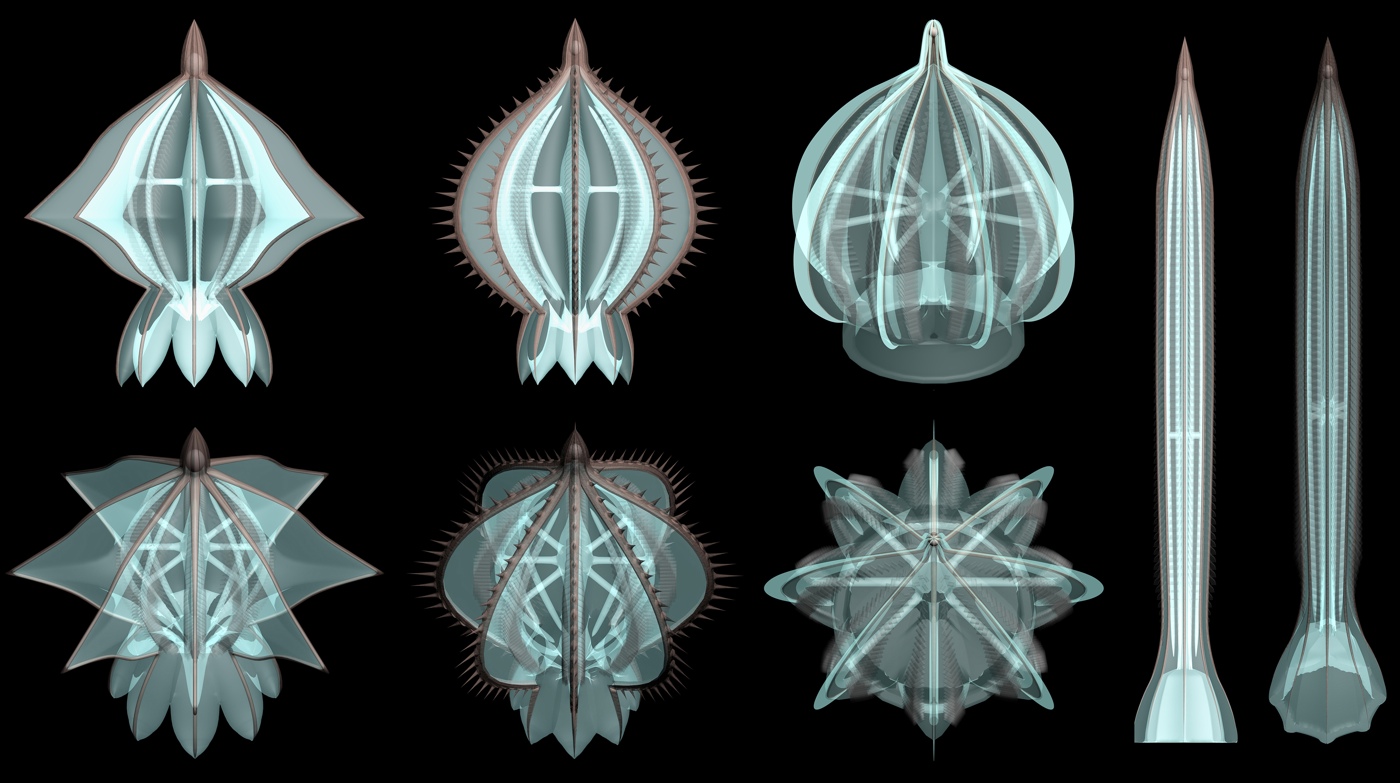

Ancient gelatinous animals that resemble Christmas tree ornaments were protected by hard, spiny skeletons and lacked the trademark tentacles of today's jellies, fossils of the long-dead jellyfishlike creatures suggest.

This is a startling snapshot of extinct comb jellies, whose modern relatives today are at least 95 percent water and sport soft bodies with no skeletons that are typically trailing tentacles.

Soft bodies don't fossilize well, and the geologic evidence for comb jellies and other members of the phylum Ctenophora (true jellyfish belong to the phylum Cnidaria) has been so meager that ancient ctenophores were long suspected to be as soft-bodied as present-day comb jellies. But new evidence from Chengjiang, a fossil-rich site in southwestern China, suggests otherwise.

Making an impression

Researchers discovered six fossils of comb jellies that lived about 520 million years ago during the Cambrian period. Preserved as imprints in rock, the fossils display distinctive features that identify them as comb jellies, including hairlike cilia that they likely used for swimming. But unlike modern ctenophores, they were girdled by plates, supported by spokes, and protected by spines that the study's scientists describe as "robust." [See Images of the Ancient Jellies & Other Wacky Cambrian Creatures]

Some of the fossils in the study are new to science, while others were originally described years ago and reclassified following this new analysis.

"I was most surprised when I realized they were skeletonized comb jellies," said study co-author Qiang Ou, of the China University of Geosciences, in Beijing. "That they were overlooked is more or less because such fossils are very rare."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Voracious predators

Almost as surprising as the skeletons was something the ancient jellies didn't have: tentacles. Most modern comb jellies have non-stinging tentacles armed with specialized sticky cells that help the gelatinous blobs catch their prey. But not all ctenophores possess tentacles, so perhaps the ancient jellies hunted like those tentacle-free animals, known as lobate ctenophores, do.

"They feed by surrounding prey with their large fleshy lobes, trapping them in an ever-contracting dome of flesh," said Rebecca Helm, a biologist at Brown University, who was not involved in the study. "Prey is forced closer and closer to the ctenophore mouth, until eventually it is consumed."

The Cambrian comb jellies could have done the same, engulfing prey that may even have included other ctenophores.

Armor for a Cambrian arms race

As for why the ancient comb jellies were so armored, the researchers suggest the bony structures could have supported jellies' vulnerable bodies, and protected them against predators and environmental damage.

Perhaps most intriguing about this discovery is that it places one more group of animals with skeletons in the geologic period known as the Cambrian explosion, an evolutionary event in which a slew of various animals burst onto the scene.

The discovery suggests that during the earliest days of life on Earth, diverse life forms "armored up," as intense competition drove specialization of both defensive and predatory structures, the researchers said.

The finding is detailed today (July 10) in the journal Science Advances.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.