Barefoot Walking Gives You Calluses That Are Even Better for Your Feet Than Shoes, Study Suggests

Ah, summer. Soft breeze in your hair, grass between your toes, nasty calluses on your feet from going barefoot…

Don't fear those calluses, though. New research has revealed that foot calluses — thickened skin that forms naturally when one walks barefoot — have evolved to protect the feet and provide for comfortable walking in perhaps ways that shoes can't match.

Unlike shoes, foot calluses offer protection without compromising sensitivity or gait, according to a study published today (June 26) online in the journal Nature. Shoes, in contrast, reduce sensitivity in the foot and alter the way that the impact forces transfer from the foot to joints higher up the leg.

The researchers — from institutes in the United States, Germany and Africa — stressed that their findings don't demonstrate that walking barefoot is healthier than walking in shoes. At its core, the study is about human evolution.

Yet the fact that we have evolved to walk barefoot, and that barefoot walking is mechanically different from walking in shoes, may imply that going barefoot can impart certain long-term health benefits worth investigating, the researchers said.

"It is fun to figure out how our bodies evolved to function," said Daniel Lieberman, professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, who co-led the study. "The sensory benefits of being barefoot might have health implications, but these need to be studied."[The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body]

For most of human's 200,000-year existence, we walked barefoot. The oldest discovered footwear dates to about 8,000 years ago, although there is indirect evidence of sandals and moccasins tens of thousands of years before this, the researchers said. Cushioned shoes are even more recent – only about 300 years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

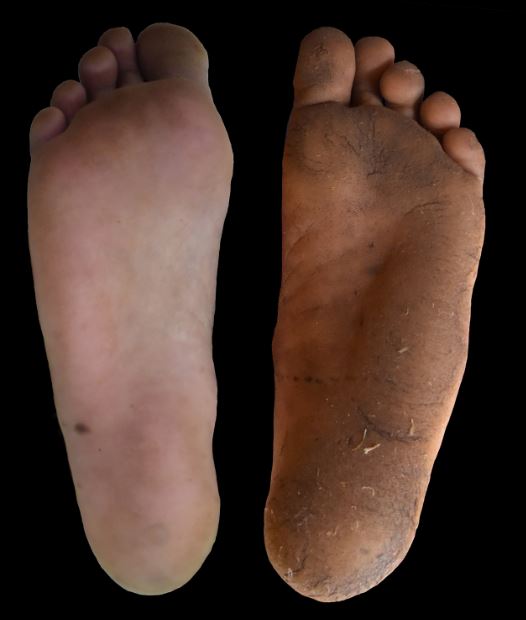

Because calluses are the evolutionary solution to protecting the foot, Lieberman's team set out to assess how these formations might differ from shoes in maintaining grounding and comfort. Their study examined the foot calluses of more than 100 adults, the majority from Kenya. About half of the subjects walked barefoot most of the time, and half mostly wore shoes.

Among the barefoot walkers, the thickness of the calluses did not dampen tactile sensitivity, or the ability of the foot to feel the sensation of the ground while walking. Shoes, with their cushioned bottoms, clearly mute this sensation.

However, very thick calluses don't simply act like shoe cushions. The callus thickness can protect against heat or sharp objects, providing comfort and safety, like shoes can. But the sensory receptors in the foot that detect ground surface differences still transmit signals to the brain.

This uninhibited signal — that sensation of feeling the earth — may help the barefoot walker keep balance, strengthen muscles and create a stronger neural connections between the feet and the brain.

"We suggest children to walk barefoot on humid grass with the purpose to stimulate the afferents [nerves traveling to the brain] for developmental reasons," said Thomas Milani, a professorship of human locomotion at the Technische Universität Chemnitz in Germany, who co-led the study.

That is, the feedback we receive from the ground when we walk barefoot improves our proprioception, or awareness of the body in space, said E. Paul Zehr, a professor of kinesiology and neuroscience at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, who was not involved in this study. Shoes can wipe out much of that feedback, he said.

The researchers also found that walking in shoes softens the initial impact of the footstep but ultimately delivers more force to the joints compared with what is seen in thick-callused individuals. This, too, may have health implications for the knees and hips, something that should be studied, the researchers said.

Zehr, an expert in the neural control of human locomotion, as well as an author of science books about the possibility of actually becoming Batman, Iron Man and Captain America, described the group's results on impact forces as "robust and interesting."

He added that one of the study's limitations is that tactile sensitivity was assessed at rest, with a device that sent vibrations into the sole, and so these results may not necessarily hold true for walking. "

"The nervous system is heavily task-specific, such that sensory inputs have differential effects when…comparing sitting, standing, walking and running," he told Live Science.

Barefoot walking isn't the best idea for everyone, despite its evolutionary basis. People with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy can wound their feet and not realize it. Lieberman's team would like to investigate the practicality of wearing thin sandals or moccasins, which might allow for a lot of tactile stimulation compared to cushioned shoes but offer added protection from abrasions.

- 7 Weird Facts About Balance

- Evolution and Your Health: 5 Questions and Answers

- 10 Amazing Things We Learned About Humans in 2018

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.