Hurricane Monitoring to Improve in 2008

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

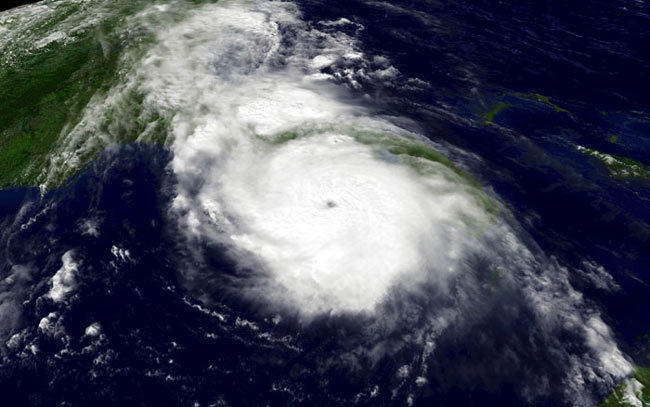

Batten down the hatches! This year's season, which kicks off on Sunday, is expected to be another busy one, according to forecasters.

But the National Hurricane Center (NHC) is prepared: Forecasters are implementing a new plan to continually monitor a storm's strength in the hours before it makes landfall with the hopes of giving coastal communities better warnings.

In 2004, Hurricane Charley rapidly intensified from a Category 2 to a Category 4 storm — winds jumped from 110 mph (175 kilometers per hour) to 145 mph (235 kph) — in the six hours before it slammed into Florida's southwest coast, causing widespread destruction in the unprepared communities. Charley killed 10 people in the United States and caused an estimated 14 billion dollars in damages, according to the NHC, some of which an earlier warning might have prevented.

To monitor the intensity of incoming storms, the NHC dispatches planes that drop instrument packages into the storm to get data on its wind speeds and pressure. But logistically these aircraft can take readings no more than every hour or two, which means that any sudden drop in pressure (the mark of an intensifying storm) and increase in winds may be difficult to anticipate.

So researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Co., and the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., devised a way to use the Doppler radar network established along the Gulf and Atlantic coastlines to scan a storm and provide information on its winds and pressure every six minutes.

Usually, no single radar could estimate the winds or pressure, and the radars are spaced too far apart to monitor a storm. But the researchers devised a technique, dubbed VORTRAC (Vortex Objective Radar Tracking and Circulation), where data from the closest radar to the storm can be combined with general knowledge of hurricane structure to map out a storm's winds. The pressure can then be inferred from this information.

Researchers tested out the technique retroactively on Hurricane Charley and found that "it can capture sudden intensity changes in potentially dangerous hurricanes in the critical time period when these storms are nearing land," said project team member Michael Bell of NCAR.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The NHC tested out the technique during last year's season and are ready to begin using it full-time.

"VORTRAC will enable hurricane specialists, for the first time, to continually monitor the trend in central pressure as a dangerous storm nears land," said project team member Wen-Chau Lee of NCAR.

The improved predictions this technique could help generate may be good news as forecasters currently expect eight hurricanes to form in the Atlantic basin this season, with four of those becoming major storms (Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson scale).

- Video: Learn What Fuels Hurricanes

- Quiz: Test Your Hurricane Knowledge

- 2008 Hurricane Guide

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus