US-China Climate Accord Gives Hope for Global Agreement

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The United States and China surprised climate-policy watchers this week by announcing a rare accord to cut carbon pollution. As details of the agreement are released, experts are hopeful that cooperation between the world's two biggest economies, and two biggest carbon emitters, bodes well for an as-yet elusive global climate pact.

"For many years, the reluctance of the U.S. and China to make strong commitments has been an oft-used excuse by other countries to not take action," said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication.

"In fact, many in the U.S. Congress have resisted taking action because they argued that China wasn't acting," Leiserowitz told Live Science in an email. "And many Chinese leaders have long used the same argument about the United States to avoid making their own commitments. This very public and early agreement by the two largest national emitters in the world should help break the long-standing logjam in the international negotiations." [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World]

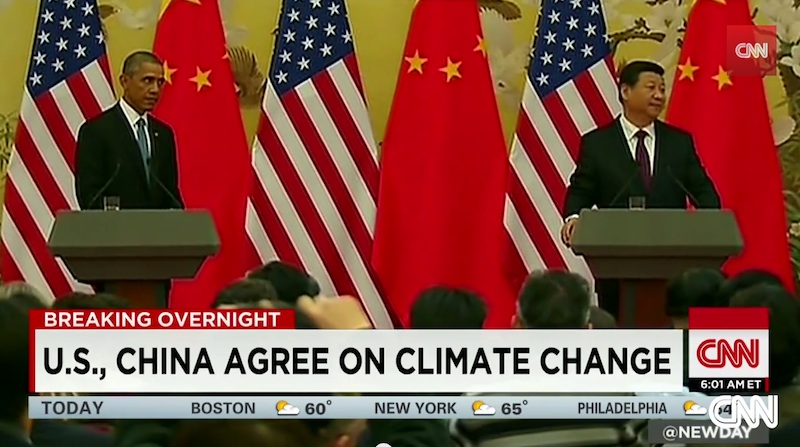

On the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Beijing, U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping announced their goals to cut emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), the main culprit behind human-caused global warming.

For its part of the deal, the United States pledged to cut its emissions by 26 to 28 percent below the 2005 level by 2025. (Obama had already set a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 17 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2020.)

"This is an ambitious goal, but this is an achievable goal," Obama said.

China, meanwhile, for the first time, agreed to hit its peak carbon-dioxide emissions around 2030. The nation also aims to have nonfossil fuels make up 20 percent of its primary energy consumption by 2030. Effectively, this means that over the next 16 years, China will have to deploy an additional 800 to 1,000 gigawatts of power from nuclear, wind, solar and other zero-emission energy sources. That's close to the total current electricity capacity in the United States, according to the White House.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There's a real energy in the air around here about this breakthrough," said Keith Gaby, director of communications at the U.S.-based Environmental Defense Fund. "We think it's hugely significant."

Last month, the European Union set its own goal to stop the increase of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 and reduce them by at least half of 1990 levels by the middle of this century. Gaby said it's important that the world's three biggest economic blocs are now moving in the same direction on climate change. And he was optimistic that the agreement would add diplomatic momentum to talks leading up to next year's United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris. [In Photos: World's Most Polluted Places]

During the 2015 climate conference, members of the United Nations are expected to hash out a more thorough, legally binding global agreement to curb the damaging effects of climate change. Most countries are expected to announce their intended carbon-cutting pledges in the first quarter of 2015.

U.N. climate leaders applauded the "clear and early leadership" of the United States and China.

Yet, the announcement didn't draw cheers from all sides. U.S. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Republican from Kentucky who is likely to become the majority leader come January, told reporters Wednesday (Nov. 12): "I was particularly distressed by the deal that [Obama] has apparently reached with the Chinese on his current trip, which, as I read the agreement, requires the Chinese to do nothing at all for 16 years, while these carbon emissions regulations are creating havoc in my state and other states around the country."

But McConnell's interpretation ignores the serious changes China will have to make if it wants to meet its goal by 2030.

"It's not as if China can flick a switch in 2030 and suddenly peak its emissions," said Elliot Diringer, climate policy analyst and executive vice president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. "It's like turning a supertanker. You need to get a big head start."

Nonetheless, several uncertainties still loom. Elizabeth Economy, director for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, noted that there are questions about how Chinese officials will collect their data and prove they're meeting international standards.

"There's a lot to be done at a granular level to ensure that China's able to meet its pledge," Economy said, but she added, "It is important that they've set this out publicly."

It's also not clear what China's level of CO2 emissions will be when its peak occurs, Economy said. Lynn Price, leader of the China Energy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, agreed that this an "important consideration." If current trends continue, China could hit a peak of 12 to 15 gigatons of CO2 between 2038 and 2040, but in a more ambitious scenario, China may peak at 10 to 11 gigatons of CO2 between 2025 and 2030, Price explained in a statement.

"When we compare China's 2030 target to the results of a number of recent or ongoing studies of China's energy and emissions pathways to 2050, this appears to be a relatively ambitious date to achieve a CO2 emissions peak and implies a meaningful effort beyond business-as-usual," Price added.

The United States, too, will need to move beyond business-as-usual policies to drastically cut carbon emissions, even though the White House said its target is "achievable under existing law."

"The U.S. target presumes policies that are not yet in place," Diringer told Live Science. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) unveiled a proposal in June to cut carbon emissions from U.S. power plants by 30 percent from 2005 levels over the next 25 years, but that plan is still pending approval. The rule will likely face resistance from opponents of emissions regulation in the courts and in Congress, Diringer said.

Already, Senate Republicans are looking at passing measures that would prohibit federal authorities from enforcing the EPA emissions rule or give states the option of not complying with it until litigation is resolved, The Washington Post reported.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus