Only 1 Person Has Been Cured of HIV: New Study Suggests Why

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

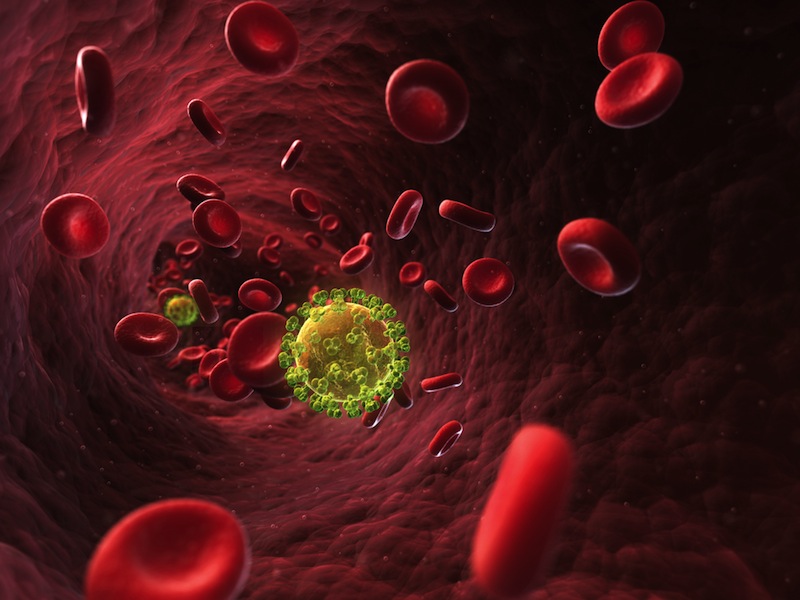

To this date, only one person is thought to have been cured of HIV — the "Berlin patient" Timothy Ray Brown. But no one is exactly sure which aspect of Brown's treatment may have cured him.

Now a new experiment on monkeys provides more evidence that a rare genetic mutation in the person who donated bone marrow to Brown may have had a central role in his cure.

Brown's HIV was eradicated in 2007 after he underwent a treatment in Germany for his leukemia, a cancer of the white blood cells. In the leukemia treatment, Brown first underwent radiation to kill the cancer cells and stem cells in his bone marrow that were creating them, and then received a bone-marrow transplant from a healthy donor to generate new blood cells.

After the treatment, not only was Brown's leukemia in remission, his HIV levels also plummeted to undetectable levels, and they have remained so ever since, even though he has not been taking the antiretroviral (ART) drugs typically used to keep HIV levels low in patients. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Three possibilities

The reason the virus remains undetectable in Brown could be that the bone-marrow transplant was from a donor who had a rare genetic mutation that renders a person's CD4-T cells — the immune cells that are the main target of HIV infection — resistant to the virus.

Having this mutation, known as delta 32, results in having immune cells that have an altered form of a certain receptor called CCR5, which prevents the virus from entering the cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But it is also possible that radiation killed very nearly all of Brown's cells that contained HIV at the outset of his treatment (and hence, the donor's genetic mutation mattered very little).

Still another possibility is that the new immune cells (that were produced by transplanted bone-marrow cells) attacked Brown's original cells, in what is called "graft-versus-host disease". This could have killed any HIV reservoirs within Brown that had survived his radiation treatment.

So which is it?

Now in a small study, Dr. Guido Silvestri, a pathologist at Emory University in Atlanta, and colleaguesgave the same treatment that Brown was given to three monkeys, to find out which step in the cancer treatment might have been responsible for the eradication of the HIV.

The monkeys in the study were infected with Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or SHIV, which is a virus related to HIV that causes a disease similar to AIDS in animals. The monkeys received antiretroviral drugs for some time, to mimic the situation of HIV patients. Then, the animals underwent radiation and received a transplant of their own bone-marrow cells, which were harvested before they were infected with SHIV. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

The researchers found that radiation killed most of the animals' blood and immune cells, including up to 99 percent of their CD4-T cells. This finding left open the possibility, at this point in the experiments, that radiation could have been a key step in curing Brown by killing almost all HIV reservoirs.

The scientists also found that the transplant resulted in the generation of HIV-free blood and immune cells within a few weeks, showing that the bone-marrow transplant experiment in monkeys was successful. If the monkeys were to be found cured of HIV, the researchers would be able to rule out graft-versus-host disease, because each monkey received its own cells in the transplant.

But after the treatment, once the researchers stopped giving the monkeys antiretroviral medications, the levels of the virus rapidly rebounded in two of the three animals.

The third monkey, who had to be euthanized after developing kidney failure, had some level of HIV in a number of tissues when it died, suggesting that none of the three monkeys had been "cured" by the treatment, according to the study published today (Sept. 25) in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

The findings support the idea that although radiation can reduce HIV levels, it's not enough to eliminate all reservoirs of the virus, the researchers said. The results suggest that in the case of the Berlin patient, either the genetic mutation of the bone-marrow donor or the graft-versus-host disease "played a significant role," the researchers said.

The Berlin patient's treatment has been tried in at least two other HIV patients who also had lymphoma — cancer of the lymph nodes. However, the bone-marrow donors in those cases did not have the rare mutation in the CCR5 gene. The patients initially appeared to be free of HIV, but the virus returned after a couple of months and the patients had to start antiretroviral medication again.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus