Trees: Unlikely Culprits in Ozone Pollution

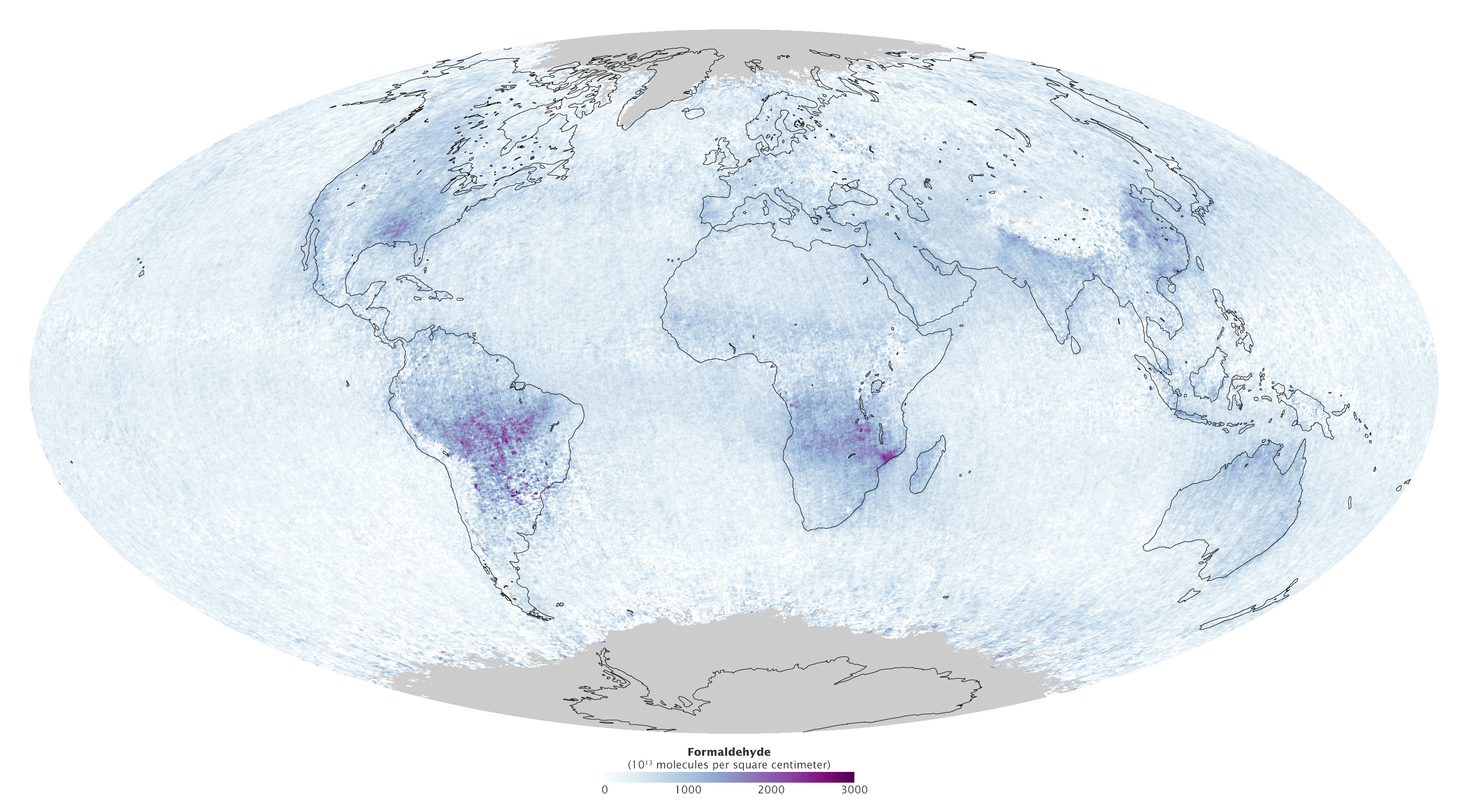

Pollution from forests? As this map shows, trees do emit compounds that can worsen ozone and increase aerosols in the atmosphere.

The purple areas on this map show places where satellites have detected formaldehyde. This chemical forms from isoprene, a volatile organic compound that trees can give off when temperatures are hot.

Trees also emit compounds called terpenes. Both isoprenes and terpenes interact with sunlight to create a sort of natural smog. This haze is where the Great Smoky Mountains get their name.

Terpenes may be the reason that climate change has yet to influence temperatures in the Smokies and the surrounding southern Appalachians, said Howard Neufeld, a plant physiologist at Appalachian State University in North Carolina. Terpenes interact with moisture in the atmosphere and reflect heat back into space, Neufeld told Live Science.

But tree pollution has its downsides, too, because it can contribute to high ozone levels near the ground, said NASA's Earth Observatory. High ground-level ozone can trap heat and exacerbate respiratory problems for people. For example, in areas where the invasive vine kudzu grows prolifically, it has been shown to boost ozone levels.

These effects have sometimes lent themselves to misconceptions, perhaps most famously, President Ronald Reagan's 1981 statement that trees pollute more than cars. [6 Politicians Who Got the Science Wrong]

"What Reagan neglected to indicate is that unhealthy levels of ozone wouldn't form without nitrogen oxides, pollutants emitted when gasoline and coal are burned," Bryan Duncan, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, told Earth Observatory.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Duncan is the head scientist for the Aura satellite, which gathered the data used to make the formaldehyde map. Satellites can't measure isoprenes, but they can detect formaldehyde, which forms as a result of isoprene emissions. Formaldehyde is also a byproduct of forest and agricultural fires. The map, from September 2013, shows high levels of formaldehyde in the Amazon, the American Southeast and parts of Africa, particularly Mozambique.

Because volatile hydrocarbon emissions from forests are so ubiquitous — and because forests absorb a lot of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, slowing climate change — it would make little sense to go after "killer trees" in the war against pollution. It would be more effective, Duncan told Earth Observatory, to reduce the other side of the equation: the nitrogen oxides produced by human activities.

"The only realistic way to try to limit ozone formation is to do something about nitrogen oxides, which is what has been done in the U.S. over the last several decades," Duncan said. "As a result, surface ozone has declined."

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing nature or general science photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus