Transparent Brain Technique Made Easier

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

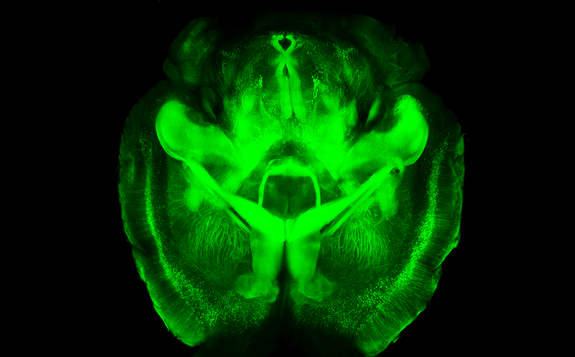

Last year, scientists developed a technique to make the brain appear transparent, yielding stunning images of the mysterious organ's inner wiring. But until now, many laboratories had trouble using it.

Many labs weren't set up to use the so-called "CLARITY" technique reliably, and the most common microscopy methods weren't designed to image an entire transparent brain. Now, the Stanford University scientists who developed the technique say they have found solutions to these problems.

"There have been a number of remarkable results described using CLARITY," Karl Deisseroth, a professor of bioengineeringand psychiatry and behavioral sciences, said in a statement, "but we needed to address these two distinct challenges to make the technology easier to use." [Video - See Transparent Mouse Brain]

The researchers described their solutions in a paper published today (June 19) in the journal Nature Protocols. It is one of the first studies supported by President Barack Obama's BRAIN Initiative, a project to develop tools for mapping the brain in the hope of understanding its function and developing potential treatments for disorders.

I can see clearly now

Normally, when you look at the brain through a microscope, it appears opaque, because of the fatty material that shrouds nerve cells and acts like the insulation on electrical wires.

The CLARITY technique works by removing this fatty covering, which makes the brain appear see-through and reveals its intricate wiring. Using this technique, Deisseroth and his colleagues imaged the neurological wiring in a mouse's brain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Originally, the researchers created a water-based gel inside the brain (usually the brain of a postmortem mouse) to hold all of its structures in place. Then they placed the brain in an electrically charged detergent that dissolved the fatty layer, and used an electric field to siphon it away.

But some labs had difficulty using the electric field method. About half of them got it to work, but others had problems with the electric voltage causing tissue damage, the researchers said.

Removing all obstacles

Now, Deisseroth and his colleagues have developed a method of pulling out the fat using chemicals and a warm bath, called "passive CLARITY." The new method takes a little longer than the original one, but is much easier to do and removes all the fat without damaging the tissue, the researchers said.

Many scientists have started using CLARITY to image donated postmortem brains from people with diseases such as autism or epilepsy, to understand them and discover potential treatments. The new, passive method minimizes any risk of damaging these valuable clinical samples, the researchers said.

Next, Deisseroth and his team addressed the problem of microscopy methods. Often, scientists will use colorful probes to stain a tissue or type of cell in the brain, which makes it glow green, blue or some other color when certain types of light are shone on it. With CLARITY, these colors can shine through the whole brain.

The problem is, these probes get bleached and stop working after being exposed to too much light. Scientists usually image the brain point-by-point, so producing an image of an entire brain takes longer than the probes normally last.

To get around the issue, Deisseroth's team adapted a technique known as light sheet microscopy, in which an entire plane of tissue can be scanned at a time. Using this technique, researchers should be able to image whole brains without the probes getting bleached, the researchers said. Deisseroth's lab provides free training courses on how to use the CLARITY technique.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus