Brain Changes in Autism Likely Start Before Birth

A discovery of distinct patches of altered brain cells in children with autism suggests the condition starts before birth, during the brain development stages in the second and third trimester of pregnancy.

In a study of postmortem brain tissue, researchers examined donated samples from 11 children with autism and 11 children without the condition ages 2 to16, and used special techniques to detect and visualize specific types of neurons in the brain's outer layer, the cortex.

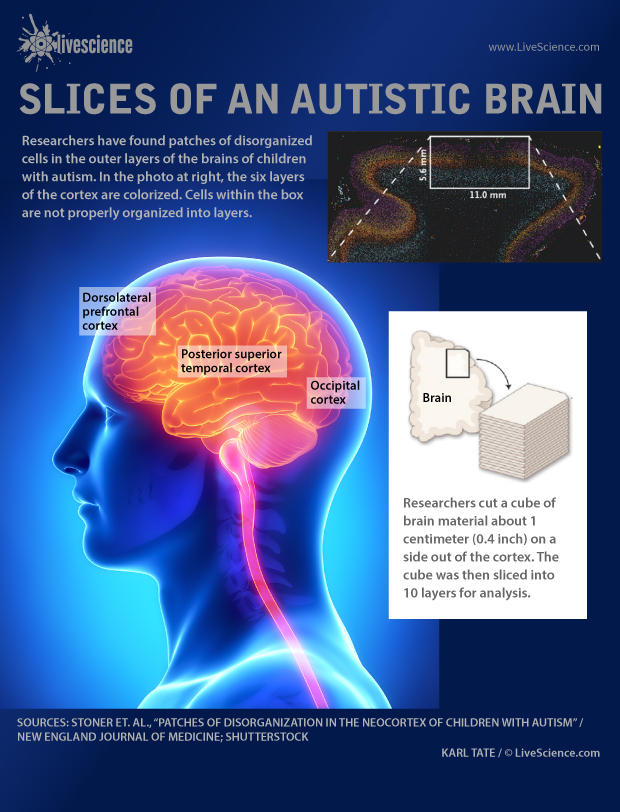

They found dense patches in the cortex containing irregular shaped neurons residing in the wrong cortical layers. These patches were 5 to 7 millimeters (about 0.2 inches) long, and were found in the frontal and temporal cortexes of 10 of the 11 children with autism, but only one of the 11 unaffected children, according to the study published today (March 26) in the New England Journal of medicine. [10 Fascinating Brain Findings]

"These patches are not like a lesion, or loss of cells. The cells are there, but they haven't become what they were supposed to, in the layer they were supposed to be in," said study researcher Eric Courchesne, a professor of neuroscience in University of California, San Diego and director of the UCSD Autism Center.

"The patches were found in frontal and temporal cortexes, areas that are important for social interaction and language, but not in the occipital cortex that is an area handling visual processing, which is pretty good in autism," Courchesne said.

In the womb

The findings point to a disruption in the development of cortical layers, which happens during the second and third trimester of pregnancy.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

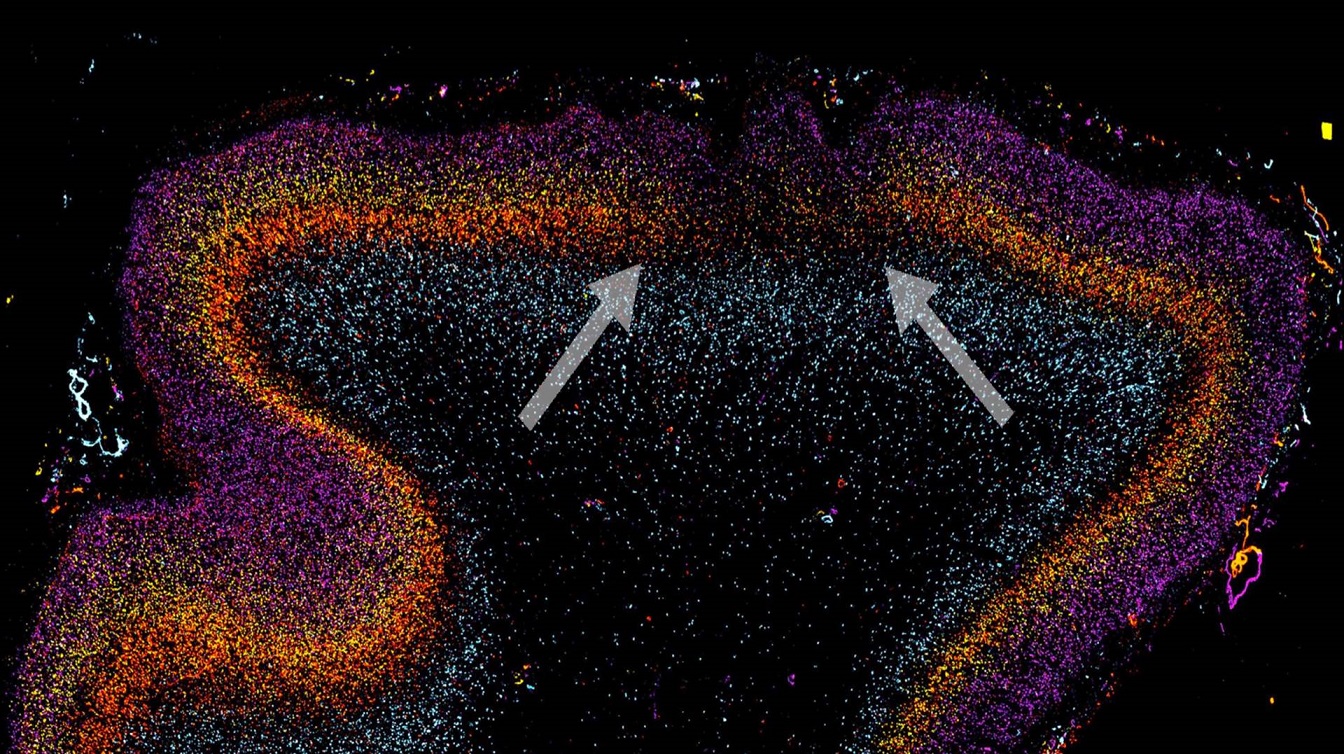

The human cortex has six layers and in each layer there are specific type of cells that reside in their designated layers.

These cells have specific genetic names, or signatures. "In a normal brain, a particular gene marker should be expressed that is held out like a sign by a certain type of cell, like pyramidal cells, in a certain layer, like layer 5," Courchesne said.

Using cell's specific genetic markers, researchers can color-code them. The result is a colorful image of a slice of the cortex that resembles a folding rainbow. [See image]

In the study, researchers found small sections where the coloring looked mixed up, showing the right cell-types are not found in their right places.

Moreover, those cells hadn't fully become what they were supposed to be.

"We expected that we would see the cell-types, but in the wrong location," Courchesne said, which would have been a migration effect, meaning cells haven't reached their right destination.

"But we saw a failure of normal gene expression of both cell-types and their layers," he said.

Previous research on human fetus has shown that cortical layers develop and become distinct from each other between 19 and 30 weeks of pregnancy. Severe disruption in this stage of development can result in cephalic disorders in which the brain, sometimes visibly, looks different.

"There's a lot of different public opinions about what might start off autism, a lot of them have to do with something happening during infancy or early childhood. But this is strong biological evidence, that it started in the womb."

Tip of the iceberg

Researchers had previously found that children with autism had 67 percent more brain cells, which also points to the second trimester in pregnancy, when brain cells are generated, Courchesne said.

Two genetic studies have previously reported several gene candidates that are likely to be involved in autism, and are linked to cell development in the frontal and temporal cortical layers.

"Those predictions have a lot of similarities to our actual finding from brain tissue," Courchesne said.

It's not clear what may have affected the normal development of cortical layers, but it's likely a combination of genetic factors and the conditions inside the womb.

"We don't know for sure. It could be that the mom was exposed to viruses, bacteria, toxins, or stress. Those are possibilities that could interact with genetics," Courchesne said.

"In a way this findings is a window back in time. We speculate that something disrupted the normal formation of cortical layers in those patches," Courchesne said, "This may be the tip of the iceberg, to see just how the autistic cortex might be affected at early ages."

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.