Peering Inside the World Cup's Brazuca Ball

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Nikhil Gupta is an associate professor in the Composite Materials and Mechanics Laboratory of the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department at New York University Polytechnic School of Engineering. The author contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

By all measures, soccer is staggeringly popular. The 2010 FIFA World Cup final was watched by more than 700 million people, and the tournament games were viewed by almost half the world's population.

Since 1970, Adidas has been designing new soccer balls for every World Cup, many incorporating materials and technologies that were innovative advances for their time. The amazingly skilled players assembled at the World Cup undeniably merit the best equipment that present-day technology can develop.

The "Brazuca" ball, which Adidas designed for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, is the latest such example of cutting-edge engineering and advanced materials. This ball is designed to have a more accurate and repeatable flight path, and after being kicked, it regains its shape more quickly than previous World Cup balls. The Brazuca is also resistant to moisture and maintains a uniform shape and weight even in the harshest environmental conditions.

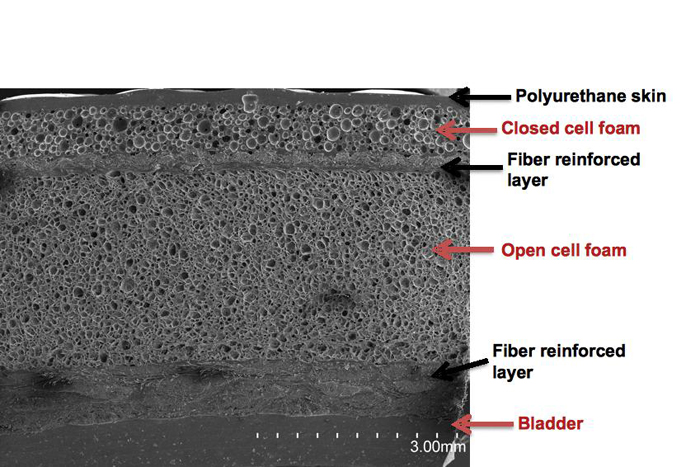

Such a wide range of attributes in a single ball is possible because of an innovative combination: The Brazuca has two layers of fiber reinforced composites and two different types of foam wrapped inside a leather-like outer surface made of a polymer called polyurethane. (The construction and major features of the Brazuca ball are explained in this video.)

It's easy to see the bladder that holds air as the innermost layer, and the shell of the ball (although it is only a couple of millimeters thick), but when with a high-powered electron microscope, you can see see four more layers.

The thicker layer of open-cell foam enclosed between two fiber-reinforced composite layers provides the desired softness under compression during kicking or heading the ball. The two fiber-reinforced layers also help in springing the ball back into shape immediately after it is kicked.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The syntactic foam layer is also made of an elastic material to have additional softness and flexibility. The fiber-reinforced layers take most of the pressure when the ball is inflated and keep the foam layers flexible.

The soccer balls of previous years were constructed by stitching the panels together. However, the Brazuca ball uses thermal bonding, which eliminates stitches and provides a smooth path for airflow in the grooves between the panels.

Only six panels are used in constructing the ball, compared to the eight panels used in 2010 World Cup ball Jabulani and the 32 panels used in most of the older balls. The surface of the ball also has a fine texture. This texture is expected to provide pathways for air flow during the glide of the ball and to keep the trajectory stable.

With a great ball in play, let's sit back, enjoy the skills of the players, and watch a great tournament!

The author's most recent Op-Ed was "How Submarine Foams Withstand the Crushing Pressures of the Deep Sea." Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus