Keeping Time: Months and the Modern Calendar

Our modern Western calendar is almost entirely a Roman invention, but it has changed significantly throughout history. Each name and number from our calendar is steeped in tradition and history. Perhaps you’ve heard a few tales about them?

- Myth No. 1: The Romans originally used a 10-month calendar, but Julius and Augustus Caesar each wanted months named after them, so they added July and August. This set the last four months askew: September (seventh month), October (eighth month), November (ninth month) and December (10th month) are now the ninth, 10th, 11th and 12 months.

- Myth No. 2: August originally had fewer days than July. To even it up, Augustus took a day away from February.

Almost everything about these supposed factoids is wrong. First we must put to rest this notion that Julius Caesar ruined the calendar. By the time of the Caesars, the year already had 12 months, and Julius actually changed an incredibly broken and bureaucratic system. Our modern calendar is so similar to his for this reason, but we’ll get to that later. While it’s true the earliest Roman calendar used 10 months, the real reason the month names don’t match up with their numeric positions is that the year used to begin in March.

The lunar calendar

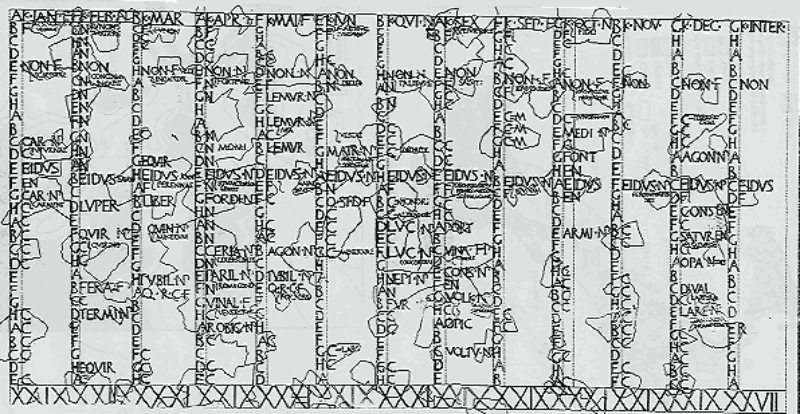

The Roman calendar was based on an older lunar calendar. The first day of each month, or the “Kalends,” occurred on new moons. The “Nones” corresponded to waxing half-moons, and the “Ides” to full moons. Dates were written as a countdown to each of these markers. A date such as May 2 was written as “the sixth day before the May Nones” or "a.d. VI Non. Mai." In this case, "a.d." stands for "ante diem," or "before the day." It should not be confused with "A.D." or "anno domini," which designates the number of years since the birth of Jesus — a system that wouldn’t be invented for another 1,200 years.

The calendar year was 10 moons long, and the remaining (roughly 70) days of winter occurred without being assigned a month name. The beginning of the year (and the starting of the calendar) signaled that farmers should trellis vines, prune trees, and sow spring wheat. This was the time that workers could expect equal parts night and day. New Years was celebrated on the first new moon before the spring equinox. The “Ides of March”, now observed on March 15th, was originally the first full moon of the New Year. Remnants of this lunar calendar still exist, such as the English words “month” and “moon” having the same roots.

The calendar of Romulus

Like many civilizations, the Romans transitioned away from a lunar calendar to one that better reflected the seasons: a solar calendar. At the founding of Rome around 753 B.C., the original calendar (said to be of Romulus himself) looked like this:

- Martius (31 days) — in honor of Mars

- Aprilis (30 days) — in honor of Fortuna (later Venus or Greek Aphros)

- Maius (31 days) — in honor of Maia

- Iunius (30 days) — in honor of Juno

- Quintilis (31 days) — fifth month

- Sextilis (30 days) — sixth month

- September (30 days) — seventh month

- October (31 days) — eighth month

- November 30 days) — ninth month

- December (30 days) — 10th month

This made a calendar year of 304 days. The choice in month lengths is not well understood, though it’s likely that scholars noticed that spring, summer and fall were each slightly longer than three moon cycles (compare the known lengths of 92.8, 93.7, and 89.9 days against a three-moon cycle of 88.6 days). In this calendar the Kalends, Nones, and Ides were separated from the moon phases, and instead each occurred on the 1st, 7th, and 15th of each month.

As before, the remaining (now roughly 60) winter days were not considered part of the calendar. The calendar would start each year with the first day of spring falling a few days after the Ides of March. This margin of winter days not belonging to the calendar is how the early Romans managed not knowing the precise year length.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The calendar of Numa

Around 713 B.C., Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, reformed the calendar significantly. The calendar was becoming important to more than agriculture, so it was necessary to assign the roughly 60 monthless days to two new months. Numa also gave each month an odd number of days, which was considered to be lucky:

- Martius (31 days)

- Aprilis (29)

- Maius (31)

- Iunius (29)

- Quintilis (31)

- Sextilis (29)

- Septembris (29)

- Octobris (31)

- Novembris (29)

- Decembris (29)

- Ianuarius (29) — in honor of Janus

- Februarius (28, 23 and 24) — for the purification festival of Februa

- Intercalaris (27) — Intercalary month

This year totaled 355 days, whichwould still come out of sync with the seasons. So in some years, extra days were added, which is called "intercalation." In these years, extra days were placed within the second half of February. Ideally, year lengths would run a four-year cycle of 355 - 377 - 355 - 378 days, averaging out to 366.25 days. Modern readers will notice this is a day too long, but in the end this did not matter because intercalations became a manner of politics rather than seasonal synchronicity.

The new months of January and February were placed at the end of the religious year, but they soon became associated with beginning of the civil year. By around 450 B.C. January was generally considered the first month of the year.

The years of confusion

Intercalations were determined by the Pontifices, high-ranking state priests who often held political power as well. Because a Roman magistrate's term of office corresponded with a calendar year, the power of intercalation was prone to abuse: the priests could lengthen a year in order to keep an ally in office, or shorten it when an opponent was in power. Also, since intercalations were often determined so close to their announcement, the average Roman citizen often did not know the date, particularly if they were some distance from the capital.

These problems became particularly acute in the years leading up to the Julian reform when there were only five intercalary years and there should have been eight. This time was known as “the years of confusion.”

The Julian calendar

Julius had spent the years 48-46 B.C. in Egypt, where he became aware of Egypt’s fixed-length 365-day calendar. When he returned to Rome, he called together a council of the best philosophers and mathematicians in order to solve the problem of the calendar. They decided the calendar would combine the Roman month names, the fixed length of the Egyptian calendar and the 365¼ days known by Greek astronomy.

Ten days were added to the year to form a regular Julian year of 365 days. Two days were added each to Januarius, Sextilis and December; one day each was added to April, June, September and November. No extra days were added to February, likely so as to not affect the rituals performed during this month, though a “leap day” was added every fourth year for a “leap year” length of 366 days.

At the time Julius took office, the seasons and the calendar were three months out of alignment due to missing intercalations, so Julius added two extra months to the year 46 B.C., extending that year to 445 days. This was referred to as the "last year of confusion." The new 365/366-day calendar was inaugurated the next year in 45 B.C. The calendar looked like this:

- Ianuarius (31 days)

- Februarius (28 / 29)

- Martius (31)

- Aprilis (30)

- Maius (31)

- Iunius (30)

- Iulius (31)

- Sextilis (30)

- September (30)

- October (31)

- November (30)

- December (31)

Quintilis was renamed Iulius (July) in 44 B.C. to honor Julius because it was the month of his birth. Later, in 8 B.C., Sextilis was renamed Augustus (August) to honor Caesar Augustus because several of the most significant events in his rise to power, culminating in the fall of Alexandria, occurred in that month. [Related: Spot Where Julius Caesar Was Stabbed Discovered]

This brings us to the second myth about the Roman calendar: Augustus taking a day away from February to avoid having a shorter namesake month than Julius. This myth has its origins in the writings of a 13th-century Parisian scholar named Sacrobosco. When Julius Caesar created his calendar, he alternated 31-day and 30-days months (with the exception of February which had 29 if it wasn’t a leap year) and changed the name of his birth month from Quintilis to “July.” Later, when Augustus became Caesar, the senate changed the month Sextilis to “Augustus.”

Sacrobosco proposed that Augustus’ month had a supposedly inferior number of days than Julius’, so the Senate fixed this by stealing a day from February. To avoid having three long months in a row, the senate also switched the lengths of September and October, and of November and December. This narrative is demonstrably false, particularly because it conflicts with surviving wall paintings that show the months were already irregular before Julius reformed them.

The Gregorian calendar

The Julian calendar persisted virtually unchanged for 1,600 years. Over the centuries, the Julian system of leap days — in which every fourth year got an extra day — threw the calendar off. By the 16th century, people noticed that the first day of spring had drifted 10 days ahead of the intended 20th of March. Basically, history had used a leap-day year 10 more times than was useful.

Pope Gregory XIII had a scholar named Aloysius Liliusa devise a new system that would keep the calendar in sync with the seasons and keep Easter as close to the spring equinox as possible. In the Gregorian calendar, every fourth year was a leap year; however, century years that were divisible 400 were exempted. So, for example, the years 2000 and 1600 were leap years, but not 1900, 1800 or 1700.

To get the new calendar aligned with the seasons, the pope had 10 days cut from the current calendar. Thursday, Oct. 4, 1582 (in the Julian calendar) was followed by Friday, Oct. 15, 1582 (in the Gregorian calendar). The changes were controversial. At the time, the pope only had the authority to reform the calendar of Spain, Portugal, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and most of Italy. Some nations wouldn’t switch over for hundreds of years. The British Empire (including the American colonies) did not adopt the change until 1752.

Japan adopted it in 1872, Korea in 1895, and China in 1912. Many Eastern European nations chose to opt out until the early 20th century. Greece, in 1923, was the last European country to change.

Today the Gregorian calendar is accepted as an international standard, but several countries have not adopted it, including Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Iran, Nepal and Saudi Arabia. Many countries use the Gregorian calendar alongside other calendars — Israel also uses the Hebrew calendar, for example — and some use a modified Gregorian calendar. Some Orthodox churches use a revised Julian calendar, which results in them celebrating Christmas (Dec. 25 in the Julian calendar) on Jan. 7 in the Gregorian calendar. [Related: Is It Time to Overhaul the Calendar?]

Time to find out if you've been paying attention! Prove it by taking the time to take this quiz:

Keeping Time: Months and the Modern Calendar

Robert Coolman, PhD, is a teacher and a freelance science writer and is based in Madison, Wisconsin. He has written for Vice, Discover, Nautilus, Live Science and The Daily Beast. Robert spent his doctorate turning sawdust into gasoline-range fuels and chemicals for materials, medicine, electronics and agriculture. He is made of chemicals.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus