More Hurricanes Forming Today than Century Ago

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

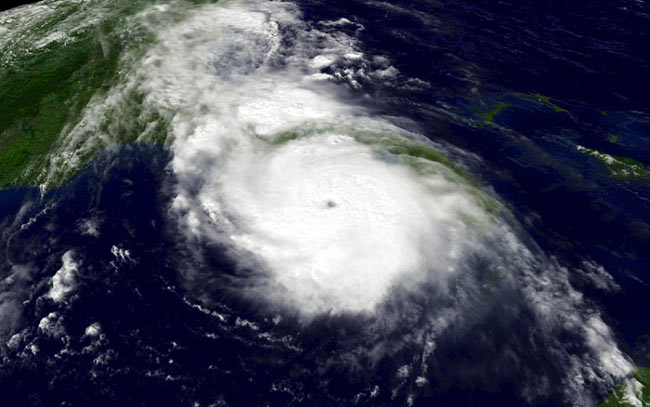

More hurricanes are forming in the Atlantic now than a century ago, most likely because of warmer ocean temperatures and changing wind patterns associated with global warming, a new study finds.

Previous research has indicated storms are stronger nowadays, but this is the first study to show a long-term increase in storm activity, a trend stretching beyond other known cycles that tend to wax and wane over a decade or two.

The researchers conducted a statistical analysis of hurricanes and tropical storms, together known as tropical cyclones, in the north Atlantic, and identified three periods since 1900 during which the annual average of tropical cyclones increased dramatically, then remained steady at an elevated level. From 1900 to 1930, there were an average of six tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic each year. That average increased to 10 between 1930 and 1940 and leapt to 15 between 1995 and 2005. The last period hasn't yet stabilized, the researchers say, and there is a possibility that hurricanes and tropical storms may be more active on average in the future.

Warmer waters

The study, detailed in the July 30 issue of the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, also found a close correlation between the increase in the average number of hurricanes and rising sea surface temperatures. These temperatures have increased by about 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit over the last century, with the increases coming before the jumps in hurricane frequency. Though the link between global warming and increased hurricane activity is inconclusive, previous studies have shown that the increase in ocean temperatures is unlikely to be a result of any natural variation.

"These numbers are a strong indication that climate change is a major factor in the increasing number of Atlantic hurricanes," said co-author Greg Holland of the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

A recent study suggested that changes in wind shear (the difference in winds at each level of the atmosphere) could be more important than warm ocean temperatures, which can feed a tropical storm or hurricane as it swirls over the water's surface. However, Holland told LiveScience that ocean temperatures aren't the direct cause of the change in hurricane frequency, but that they influence the ocean circulation, "and it's the change in the environment that changes the frequency."

Some have argued that any apparent increases in hurricane frequency are a result of better observation methods from aircraft since 1944 and satellites since about 1970, but Holland and co-author Peter Webster of the Georgia Institute of Technology say their study refutes that argument.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

MIT's hurricane researcher Kerry Emanuel, who was not involved with the study, agrees with the authors: "This new paper shows that the upward trend of the annual frequency of Atlantic hurricanes over the past century occurred largely in two upward jumps, neither of which coincided with important upgrades in the measurement of hurricanes," Emanuel said in an email interview.

More major hurricanes

While the number of tropical cyclones has increased, the percentage of them that qualify as hurricanes has remained steady, accounting for a little over half of all tropical cyclones. But the number of major hurricanes (category 3 or above) has increased significantly, the study showed.

Though the 2006 hurricane season was much quieter than the record-setting season of 2005, it would still have ranked above average a century ago.

"Even a quiet year by today's standards would be considered normal or slightly active compared to an average year in the early part of the 20th century," Holland said.

- 2007 Hurricane Guide

- Natural Disasters: Top 10 U.S. Threats

- Images: Hurricanes from Above

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus