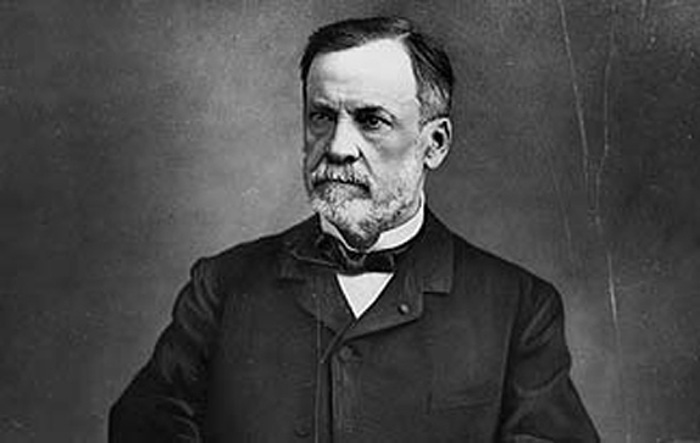

Louis Pasteur: Biography & Quotes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist whose work changed medicine. He proved that germs cause disease; he developed vaccines for anthrax and rabies; and he created the process of pasteurization.

Family and education

Louis Pasteur was born on Dec. 27, 1822, in Dole, France. Pasteur’s father was a tanner and the family was not wealthy, but they were determined to provide a good education for their son. At 9 years old, he was admitted to the local secondary school where he was known as an average student with a talent for art.

When he was 16, Pasteur traveled to Paris to continue his education, but returned home after becoming very homesick. He entered the Royal College at Besançon where he earned a Bachelor of Arts. He stayed to study mathematics, but failed his final examinations. He moved to Dijon to finish his Bachelor of Science. In 1842, he applied to the Ecole Normale in Paris, but he failed the entrance exam. He reapplied and was admitted in the fall of 1844 where he became graduate assistant to Antoine Balard, a chemist and one of the discoverers of bromine.

Crystallography

Working with Balard, Louis became interested in the physical geometry of crystals. He began working with two acids. Tartaric acid and paratartaric acid had the same chemical composition, but appeared different when the crystals were viewed under a microscope. How could chemically identical substances look different? Louis found that, when placed in solution, the two substances rotate polarized light differently.

Louis then used his microscope and a dissecting needle to painstakingly separate crystals of the two acids. He discovered that two types of crystals were mirror images of each other. This was the first evidence of the chirality of chemical compounds. His thesis on this work earned him a double doctorate in physics and chemistry in 1847. In 1848, he was offered a post at the University of Strasbourg, where he met and married Marie Laurent. They had five children, three of whom died of typhus, an event that later influenced Pasteur’s interest in infectious disease.

Fermentation and pasteurization

While in Strasbourg, Pasteur began studying fermentation. His work resulted in several improvements to the industries of brewing beer and making wine. In 1854, Louis accepted a position at the University of Lille, where he was asked by a local tradesman to help find out why some of the casks of fine vinegar made from beet juice were spoiling. Pasteur examined the good vinegar and the spoiled vinegar under the microscope. He knew that the yeast that caused the beet juice to ferment was a living organism. Casks producing good vinegar contained healthy yeast while those producing the spoiled product also contained microscopic rods that harmed the yeast.

Pasteur hypothesized that these small “microbes” were also living organisms that could be killed by boiling the liquid. Unfortunately, this would also affect the taste of the vinegar. By careful experimentation, he discovered that the infecting microbes could be killed by controlled heating of the vinegar to 50-60 degrees Celsius (122-140 degrees F) and then rapidly cooling. Today the process is known as pasteurization.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Spontaneous generation

In the 1860s, many scientists thought that microbial life generated from air alone. Pasteur did not believe that air was responsible. He believed that microbes attached to particles of dust multiplied when they fell out of the air into a medium suitable to their reproduction. In 1859, the same year that Darwin’s "On the Origin of Species" was published, Louis Pasteur set out to prove that microbes could only arise from parent microbes.

In order to show that dust in the air could carry microbial contamination, Pasteur took vessels containing sterile solutions of nutrient broth to several different locations. He would then briefly open the containers, exposing them to the air. He showed that vessels exposed at low altitudes with high concentrations of dust particles became contaminated with many more microbes than those exposed at higher altitudes where the air was purer.

When critics still argued that it was the air causing spontaneous generation, Pasteur devised a simple and elegant solution. He commissioned special “swan necked” glass vessels. The top of these vessels was bent in an S-shaped curve that allowed air circulation but trapped dust. When placed in such a vessel, nutrient broth never showed microbial growth, thus disproving spontaneous generation.

Silk worm crisis

Pasteur was asked to head a commission to investigate a disease affecting silk worms. Using his microscope, he noticed that adult moths and infected worms showed globules on their bodies. He decided that when mature moths with globules were allowed to reproduce, they laid diseased eggs. He instructed the silk farmers to separate all adults showing the globules and allow only healthy adults to breed. Unfortunately, the following spring these “healthy” moths produced hundreds of diseased eggs. Pasteur faced a lot of criticism over the next two years before discovering the cause.

Moths with globules were indeed ill with one disease, but actually there were two diseases killing the silkworms. The globules were one type of microbe, but Pasteur identified a second disease that was previously unsuspected. He further determined that environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity and sanitation affected susceptibility to both diseases. This work helped lay the foundations for the science of epidemiology.

Vaccines

In the spring of 1879, Pasteur was certain he had isolated the pathogen causing chicken cholera. Tests showed that chickens inoculated with a solution containing the suspected pathogen all became infected with the disease. Leaving instructions for his students to inoculate different birds at specific times, Pasteur left his lab for a holiday in Paris.

While he was gone a batch of cholera pathogen was accidently left to dry out. Students were dismayed to discover that chickens given the damaged pathogen did not become sick. When Pasteur returned they proceeded to inoculate the chickens with a new batch of cholera pathogen. A few days later, Pasteur noticed that chickens that had been given the “useless” pathogen showed no sign of being infected. Pasteur’s observation led him to the discovery that the virulence of a pathogen can be artificially altered.

In 1882, Pasteur turned his attention to the problem of rabies. Rabies is spread from contact with the body fluids of an infected victim, including saliva. A bite from a rabid animal is very dangerous and often fatal. Pasteur examined the saliva and tissues of rabid animals. He was unable to discover the microorganism responsible for causing the disease. Today we know that rabies is caused by a virus too small to be seen with the microscopes available to Pasteur.

Pasteur needed a reliable source of infectious material for his experiments. He obtained material by having several men hold down a rabid dog. He then personally forced the animal’s mouth open to collect the saliva in a bottle. Unfortunately, injecting saliva of infected animals did not reliably produce rabies in test animals. Through dissection and experimentation Pasteur found that the “causative agent” had to concentrate in the spinal cord and brain of a victim to produce the disease.

Pasteur was certain that vaccination with a weakened form of the disease followed by progressively more aggressive treatments would help build immunity. The problem of how to weaken the invisible “causative agent” was solved by his assistant, who invented a special bottle in which to dry infected tissue. Pasteur found that the longer the infectious material was dried the less likely it was to cause rabies when injected.

Over time, Pasteur developed an immunization protocol that reliably protected animals from contracting rabies. After a series of increasingly potent rabies injections given to dogs over a 12-day period, rabies extract was injected directly into their brains. To Pasteur’s satisfaction every one of the dogs resisted rabies.

Pasteur was understandably reluctant to test his treatment on human beings. Since he still could not see the microorganism that caused the disease, he had only experimental data to show that drying attenuated the causative agent. What if he injected a human being and caused a person to contract rabies?

On July 6, 1885, an emergency forced Pasteur to act. Nine-year-old Joseph Meister had been bitten repeatedly by a rabid dog. The situation was grave, the boy was certain to develop rabies and die horribly unless Pasteur treated him successfully. Pasteur reluctantly agreed to administer the painful treatment. Despite his misgivings, Pasteur’s vaccinations proved successful and Joseph Meister made a complete recovery.

Honors and death

In 1873, Pasteur was named a fellow in the French Institute of Medicine. In 1888, the French government allocated funds for the establishment of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he continued his research and served as dean of science. In 1895, while still working part time at his lab, he suffered the first of a final series of strokes. Louis Pasteur died on Sept. 28, 1895. His last words were, “One must work; one must work, I have done what I could.”

Quotes

"I am utterly convinced that science and peace will triumph over ignorance and war, that nations will eventually unite not to destroy but to edify, and that the future will belong to those who have done the most for the sake of suffering humanity."

"The Greeks understood the mysterious power of the below things. They are the ones who gave us one of the most beautiful words in our language, the word 'enthusiasm' — 'a god within.'"

"In the fields of observation chance favors the prepared mind."

"Science knows no country, because knowledge belongs to humanity, and is the torch which illuminates the world."

"There does not exist a category of science to which one can give the name applied sciences. There are sciences and the applications of science, bound together as the fruit of the tree which bears it."

"The universe is asymmetric and I am persuaded that life, as it is known to us, is a direct result of the asymmetry of the universe or of its indirect consequences."

"Posterity will one day laugh at the foolishness of modern materialistic philosophers."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus