Antarctic Hills Haven't Seen Water in 14 Million Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Water has not flowed across Antarctica's Friis Hills for 14 million years, researchers reported Tuesday (Oct. 29) at the Geological Society of America's annual meeting in Denver.

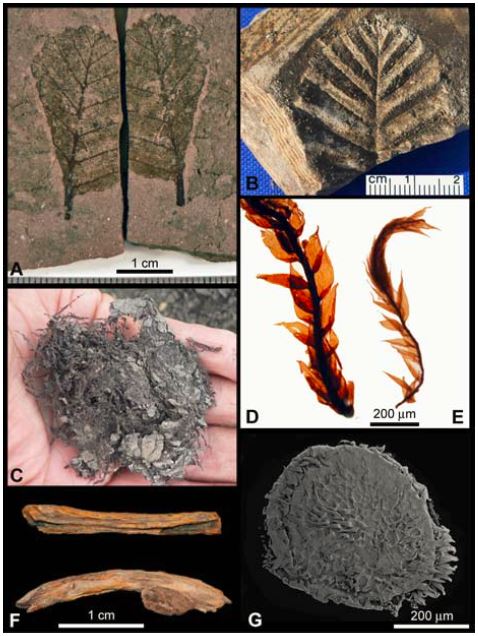

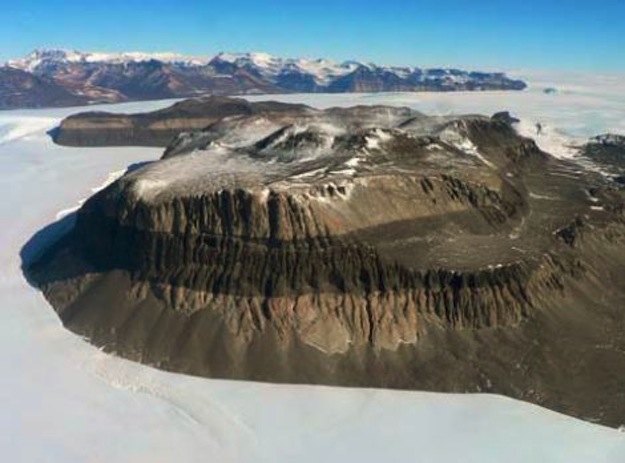

The Friis Hills rise 2,000 feet (600 meters) above Antarctica's Taylor Valley, one of the "Dry Valleys" west of McMurdo Sound. Fossils show tundra mosses and a lake once covered the flat-topped hills, when Earth's climate was warmer more than 14 million years ago. Now, thanks to blocking by nearby mountains, cold temperatures and strong winds that suck moisture from the air, the aptly named Dry Valleys receive little to no measurable rain or snow. (Sometimes, snow drifts in from nearby hills.)

To gauge ancient rainfall amounts, Rachel Valletta, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, looked for traces of a radioactive isotope called beryllium-10 in lake sediments on the Friis Hills. This rare beryllium isotope, which has more neutrons than the stable version, forms when cosmic rays collide with oxygen and nitrogen atoms. Beryllium-10 decays on a predictable time scale, allowing geochemists to estimate the age of sediments containing the isotope. [The 10 Driest Places on Earth]

Valletta tested the lake sediments for meteoric beryllium-10 — isotopes created in Earth's atmosphere and carried down to the surface by rainfall. She measured the levels at intervals from the surface down to 2 feet (60 centimeters) below ground. At the deepest levels, the isotope was undetectable. This means the beryllium-10 buried with the sediments millions of years ago has completely decayed away, and no water has trickled into the ground to replace it.

"We would have expected greater concentrations of beryllium had there been water flowing over the surface," Valletta told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. "Concentrations this low do indeed support the fact that there has been no surface water present" since the sediments were deposited, she said.

The results also suggest that this part of Taylor Valley has been extremely dry for a very long time. Other evidence for little to no rain or snow falling on Friis Hills includes ash layers with no chemical weathering caused by water, Valletta said. "I can't say that there has been no precipitation," Valletta said. "But precipitation has been extremely low in this area."

Valletta plans to use the beryllium-10 data to help track erosion rates at Friis Hills and better estimate the start of Antarctica's current cold, dry climate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus