Flying Foxes (Actually Bats) on Remote Island Studied for First Time

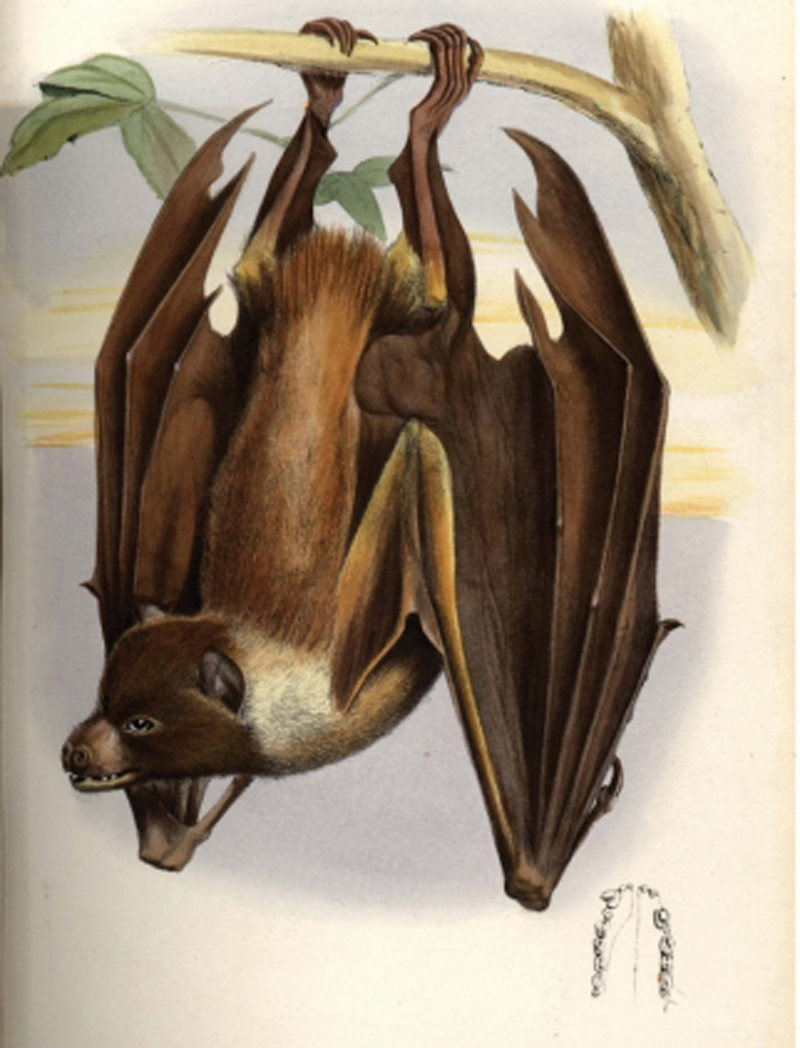

Flying foxes? Not really foxes. They're actually bats (and one of those animals with a pretty misleading name).

But though their moniker may not be accurate, they are fascinating creatures that scientists know fairly little about. Now, a new study reveals some limited details about one isolated species found on islands in the western Pacific Ocean.

Flying foxes are the largest bats on Earth, and consist of more than 60 species that live throughout remote islands of the Indian and Pacific oceans, as well is in parts of continental Asia and Australia. They are reddish-brown, ever-so-slightly resembling the color of true foxes. The largest species has a wingspan of up to 4.5 feet (1.4 meters) and can weigh up to 2 pounds (1 kilogram), more than three times larger than most North American bats, which grow to be only about a third of an ounce (10 grams) and have wingspans closer to 11 inches (27 centimeters).

Pteropus pelagicus — a relatively small species of flying fox with a wingspan of about 2 feet (61 centimeters) — inhabits the western Pacific Mortlock Islands within the Federated States of Micronesia. A German naturalist first described the animal in 1836, but little research has been conducted on the animal since then due to the logistical challenge of traveling to these remote islands. [7 Most Misleading Animal Names]

A team of naturalists based at the College of Micronesia has now conducted the first-ever field study of the Mortlock Islands flying fox population in an effort to catalog more details about how this enigmatic creature lives.

"We knew virtually nothing about it in terms of ecology other than the fact that it lived on this small set of atolls," study co-author Gary Wiles, a researcher with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

The team identified eight plant species that the animals eat, finding that they seem to prefer fruit, particularly from the breadfruit tree. As fruit lovers, they are considered frugivores. They do have intimidating caninelike teeth in the front of their mouths that look sharp enough to rip up meat, but these teeth are actually just used to carry fruit from one tree to another, Wiles said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team also found that the bats breed year-round on the islands, which separates them from most other flying fox species, which tend to have more distinct breeding periods.

"Most flying foxes are seasonal in breeding patterns, and maybe give birth to young over a couple month period," Wiles said. "But for some reason, these bats appear to breed year-round."

The researchers believe that the islands support between 900 and 1,200 bats that have no apparent native predators on the islands, but may be preyed upon by feral cats and monitor lizards that humans have introduced. Some cultures hunt flying foxes and consider them a delicacy, but residents of the Mortlock Islands do not generally hunt the animals, the researchers say.

A potentially more serious threat to the animals than predators is future sea level rise associated with climate change. The small atolls — or low-lying islands — that the animals inhabit only reach between about 3 feet to 10 feet (1 to 3 m) above sea level, and could therefore become inundated if average global sea level rises by as much as 3.2 feet (0.98 m) by 2100, as projected by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

P. pelagicus populations could potentially island hop in the event that some islands disappear before others, though this seems unlikely, Wiles said.

"They might be able to fly to another island, but if they find other bats living there, they probably wouldn't be able to form a population of their own," Wiles said. "So this is pretty much their only habitat."

This latest work, detailed Tuesday (Oct. 29) in the journal ZooKeys, only scratches the surface of P. pelagicus ecology, Wiles said, andhe hopes that it will motivate other naturalists and biologists to pursue additional studies regarding the bats' diet and breeding patterns.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.