Government Shutdown: Chilling Effects on Antarctic Research

Scientists who risk their lives for Antarctic research fear their entire field season may be canceled because of the ongoing government shutdown.

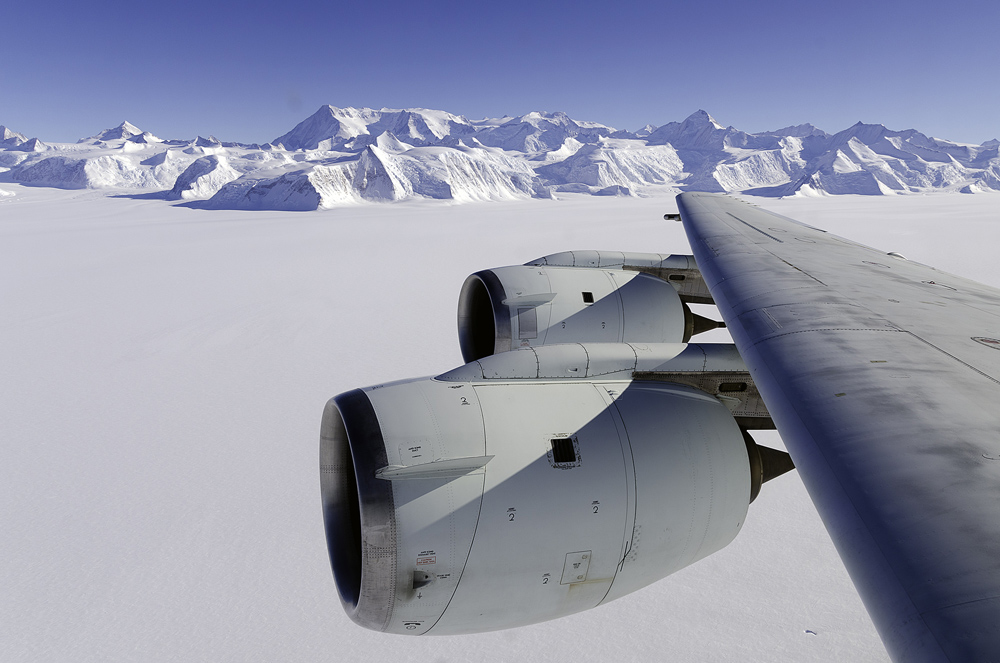

The U.S. Antarctic research program relies on government-funded planes, ships and tractors to transport scientists and equipment across the frozen ice and seas. After the Oct. 1 government shutdown, all travel stopped, except for flights to supply people already at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. And the summer research program, originally scheduled to kick off Oct. 3, is on hold until the congressional standoff ends.

Last week, contractor Lockheed Martin told researchers by email that a decision would be made this week of whether to shut down the three Antarctic research bases and leave behind a skeleton crew, Nature News reported. Lockheed Martin contracts with the National Science Foundation (NSF) to support the United States' Antarctic research program.

As of today (Oct. 7), no one has heard directly from the NSF about the fate of individual projects or the entire Antarctic program. [Weirdest Effects of the Shutdown]

In limbo

But even if the shutdown ends soon, some key Antarctic projects are already in jeopardy. Among the affected projects is NASA's IceBridge campaign, which tracks yearly changes in the polar ice sheets. Because of the furlough, NASA workers can't install equipment on the IceBridge research plane to prep for its Antarctic trip, scheduled for late October.

"If this situation continues, it will eventually cancel the mission for 2013," said Eric Rignot, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., who is involved with IceBridge. JPL is run by a private contractor, the California Institute of Technology, and is still open during the shutdown. The lead scientist for IceBridge, Michael Studinger, is at NASA's Goddard Lab and is on furlough.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

IceBridge is a six-year campaign to monitor how glaciers, sea ice and ice sheets respond to climate change. Scientists use an instrument-laden P-3 aircraft to make a year-to-year comparison, as well as to investigate new regions. IceBridge fills the gap between the defunct ICESat satellite and the planned ICESat-2, scheduled to launch in 2016.

Interrupting year-to-year projects like IceBridge wreaks havoc on the accuracy of scientist's data sets, said Robin Bell, who is involved in the IceBridge project.

"We would lose important data points in measuring how the ice sheets are changing," said Robin Bell, a senior scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York. "It is as if we decided it was a good idea to skip the annual physical," Bell told LiveScience.

"It is very valuable to have a continuous unbroken data series," added Andrew Fountain, a glaciologist at Portland State University in Oregon who works in Antarctica's Dry Valleys and is not involved with IceBridge. "Having a gap in the data makes the analysis of trends — such as warming/cooling and growing/shrinking — that much more difficult and the statistical analysis more challenging," Fountain told LiveScience by email.

Devastating effect

Outright canceling the summer field season would be especially devastating for early-career scientists and graduate students, who may rely on a single project for their data and funding.

"If we can't get to our sites, it will be another year before we have any data to work with, drastically impeding progress on our research," said Samantha Hansen, a geophysicist at the University of Alabama. Hansen planned to collect data from a network of seismometers set out on the ice last year. The project will reveal Antarctica's hidden geologic structures.

"Additionally, some stations are deployed in regions with high snow-accumulation rates, and if left unattended for another year, they could be buried completely — making them irretrievable," Hansen told LiveScience by email. "I've lost a lot of sleep worrying about this situation."

Other major projects that could be lost this year include WISSARD, the return to Lake Whillans, where microbial life was discovered last year in a buried Antarctic lake. Researchers also planned to drill ice cores to investigate climate change, study penguins and seals, and observe space from a South Pole telescope.

Editor's note: This story was updated Oct. 7 to correct that Samantha Hansen works at the University of Alabama.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.