Antarctica's Scars Hold Clues to Hidden Water

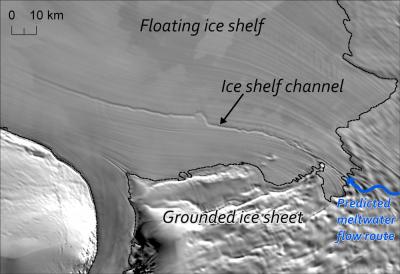

Deep furrows on Antarctica's floating ice shelves mark arch-shaped channels melted out under the ice. Thinner ice floats lower, and researchers can read the corrugated surface topography like a map that mirrors what lies beneath.

Now, a new study published today (Oct. 6) in the journal Nature Geoscience suggests that in some spots, these surface scars also signal where water drains from beneath Antarctica's giant ice sheets.

"These features on the ice shelf are very long, so it suggests the water is flowing quite steadily and consistently over time," said Anne Le Brocq, lead study author and a glaciologist at the University of Exeter in England.

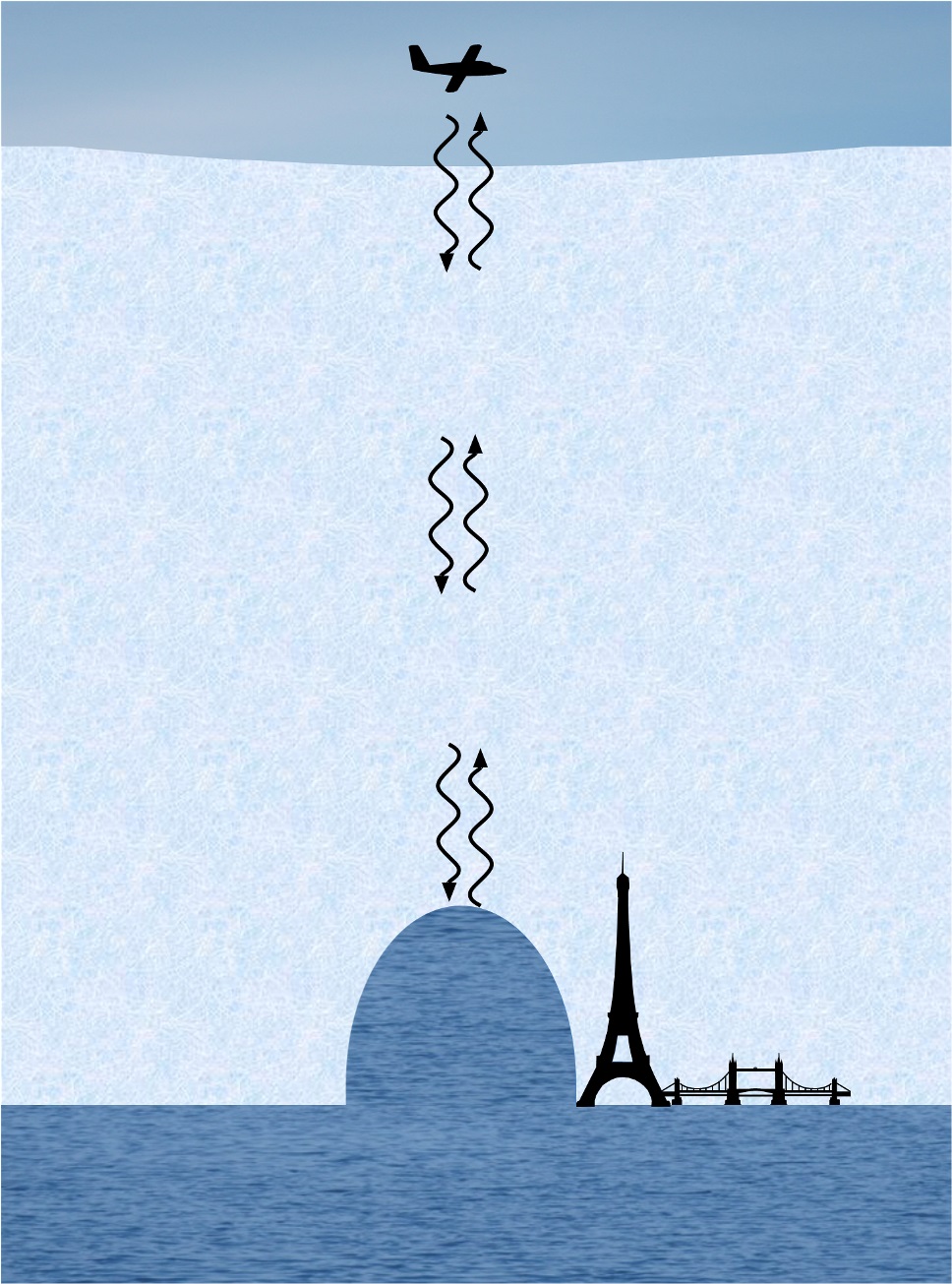

Plumbing the edge of Antarctica's ice sheets — more than 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) thick — for exiting water plumes is hard to do even with modern survey equipment. Ice sheets are attached, or grounded, to land, while ice shelves float on water. "These channels provide a tool to investigate something that is happening beneath the ice that we couldn't otherwise study," Le Brocq told LiveScience.

But researchers are keen to know whether the meltwater under the grounded ice flows like a sheet or in an organized fashion, like streams and rivers or even swamps. Predicting how these massive ice sheets will respond to global warming is difficult for climate modelers because there is little direct evidence of the key characteristics at the ice sheets' base, such as topography and water flow. Still, clues are mounting that Antarctica hosts many kinds of drainage networks, even occasional massive floods, depending on where one looks.

"You don't see these channels on every ice shelf," Le Brocq said. "We don't know the reason why."

Clues to channels

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Le Brocq and her colleagues used satellite imagery and airborne radar surveys to find meltwater channels in the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf in West Antarctica. The study confirmed that the meandering lines on top of the ice shelf match up with meltwater channels carved upwards into the bottom of the ice. One channel was nearly as tall as the Eiffel Tower — about 820 feet (250 meters) high and 985 feet (300 m) wide. [Incredible Technology: How to Explore Antarctica]

The team's next step was to create a computer model to predict how the ice would respond to an underground, streamlike water flow where it transitions from land to sea. The modeling results suggest that long, linear features like the meltwater channels would appear, Le Brocq said.

"We need to think about water flowing under the ice sheet in more focused channels than in a thin layer," Le Brocq said. "Because these features meander, we can also see how the nature of the exit point moves over time."

While scientists agree that the meltwater channels in ice shelves are long-lived features, the level of detail available in the Antarctic surveys used in the study leaves a lot of uncertainty, said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., who was not involved in the study.

"We can see a few of the big channels, but the maps are still very crude," Rignot said. "We really don't have the level of detail of the bed beneath the ice sheet to say much about water flowing at a steady rate. I think they've put their finger on the case a little more strongly, but they still come a little short in proving it."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus