Earthquake Scientist: Extend California's New Early Warning System

California will be the first state to get an earthquake early warning system, thanks to a bill signed Sept. 24. And the state's effort should be a model for a national system, one earthquake scientist argues.

Scientists in California have successfully run a test version of the system for two years. Now it's time to set up a similar earthquake warning system along the West Coast, said Richard Allen, director of the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory.

"Earthquakes are a real risk for us on the West Coast, but they come around very infrequently, so they are easy to ignore," Allen told LiveScience. "Earthquake early warning is a proven technology. If we were to have an earthquake next week, [legislators] would be all over building one because it really doesn't cost very much. Are we really going to sit on our hands and wait until we have the next earthquake, or are we going to take the steps to do it now?"

California's system

The California system will cost about $80 million to build and run for five years, but the bill does not provide funding. Instead, the law directs the state's Office of Emergency Services to identify sources of funding by January 2016 and develop standards for the statewide warning system.

Extending the warning system to Oregon and Washington would cost $120 million, Allen estimates in an editorial published today (Oct. 2) in the journal Nature. Though California shakes more often than its northern neighbors, both Oregon and Washington are at risk of a massive magnitude-9.0 earthquake from the Cascadia subduction zone, which also lies offshore of Northern California. The fault's last known earthquake was Jan. 26, 1700. The temblor sparked a tsunami that traveled to Japan and drowned trees along the U.S. West Coast.

Much of that money would be spent on hardware: A dense network of modern earthquake sensors, or seismometers, that would accurately detect and report quakes. [Video: Earthquake Early Warning System Demonstration]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After setting up enough seismometers, the next big hurdle in building a warning system is the software. The key is avoiding false alerts, such as an Aug. 8 error in Japan that shut down the nation's bullet trains.

How it works

Earthquake early warning systems are designed to detect the first strong pulse coming from an earthquake, which carries information about its size. This shock wave travels faster than the slower waves that do most of the shaking damage during a quake. The farther you are from the quake's epicenter, the more warning you get.

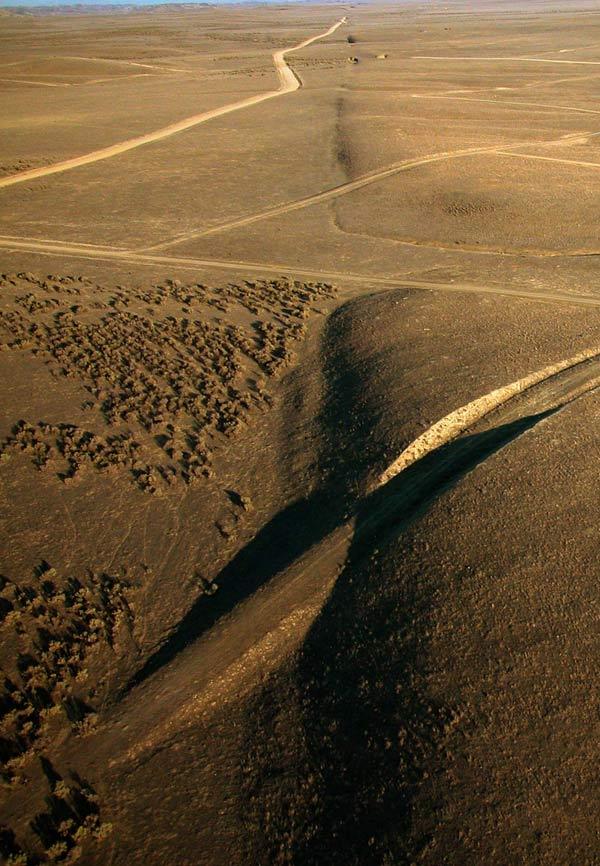

In California, the warning may be a minute, or there may be no warning at all. That's because some of the state's biggest cities are built on top of its most hazardous faults. The most famous, the San Andreas Fault, is somewhat distant from Los Angeles and San Francisco. Residents would get several seconds of warning. But much of San Francisco's urban infrastructure sits on top of the Hayward fault, which has a 31 percent chance of a magnitude-6.7 or greater earthquake in the next 30 years.

"We need to build a system that absolutely minimizes the delay in getting the warning out," Allen said.

Japan's earthquake early warning system often provides several seconds to a minute of warning because its greatest seismic hazard is miles offshore: A subduction zone similar to the Cascadia fault line. In Japan, private companies provide phone alerts, radios and other custom applications of the publicly available warnings.

Allen hopes that public-private partnerships similar to Japan's will emerge once the California warning system launches. He said the Berkeley lab is testing an Android app to provide rapid notification of new earthquakes.

The good news is that rolling out California's system will be easy if the funding ever comes through. Though the U.S. operates on a hodge-podge of seismometer networks, they all "talk" via the same software system. The California earthquake alert also collects information from the same software, making it simple to expand the system.

"There is no reason we couldn't roll it out across the nation," Allen said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience , Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.