11 Surprising Facts About the Circulatory System

Introduction

The circulatory system includes the heart, blood vessels and blood, and is vital for fighting diseases and maintaining homeostasis (proper temperature and pH balance). The system's main function is to transport blood, nutrients, gases and hormones to and from the cells throughout the body.

Here are 11 fun, interesting and perhaps surprising facts about the circulatory system that you may not know.

The circulatory system is extremely long

If you were to lay out all of the arteries, capillaries and veins in one adult, end-to-end, they would stretch about 60,000 miles (100,000 kilometers). What's more, the capillaries, which are the smallest of the blood vessels, would make up about 80 percent of this length.

By comparison, the circumference of the Earth is about 25,000 miles (40,000 km). That means a person's blood vessels could wrap around the planet approximately 2.5 times!

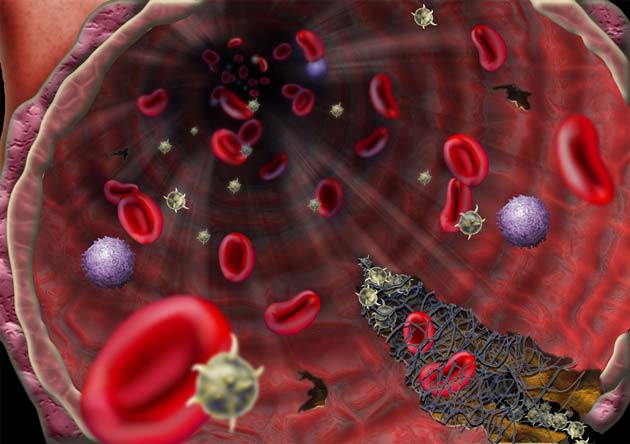

Red blood cells must squeeze through blood vessels

Capillaries are tiny, averaging about 8 microns (1/3000 inch) in diameter, or about a tenth of the diameter of a human hair. Red blood cells are about the same size as the capillaries through which they travel, so these cells must move in single-file lines.

Some capillaries, however, are slightly smaller in diameter than blood cells, forcing the cells to distort their shapes to pass through.

Big bodies have slower heart rates

Across the animal kingdom, heart rate is inversely related to body size: In general, the bigger the animal, the slower its resting heart rate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An adult human has an average resting heart rate of about 75 beats per minute, the same rate as an adult sheep.

But a blue whale's heart is about the size of a compact car, and only beats five times per minute. A shrew, on the other hand, has a heart rate of about 1,000 beats per minute.

The heart needs not a body

In a particularly memorable scene in the 1984 film, "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom," a man rips out another man's still-beating heart. While easily removing a person's heart with your bare hand is the stuff of science fiction, the heart actually can still beat after being removed from the body.

This eerie pulsing occurs because the heart generates its own electrical impulses, which cause it to beat. As long as the heart continues to receive oxygen, it will keep going, even if separated from the rest of the body.

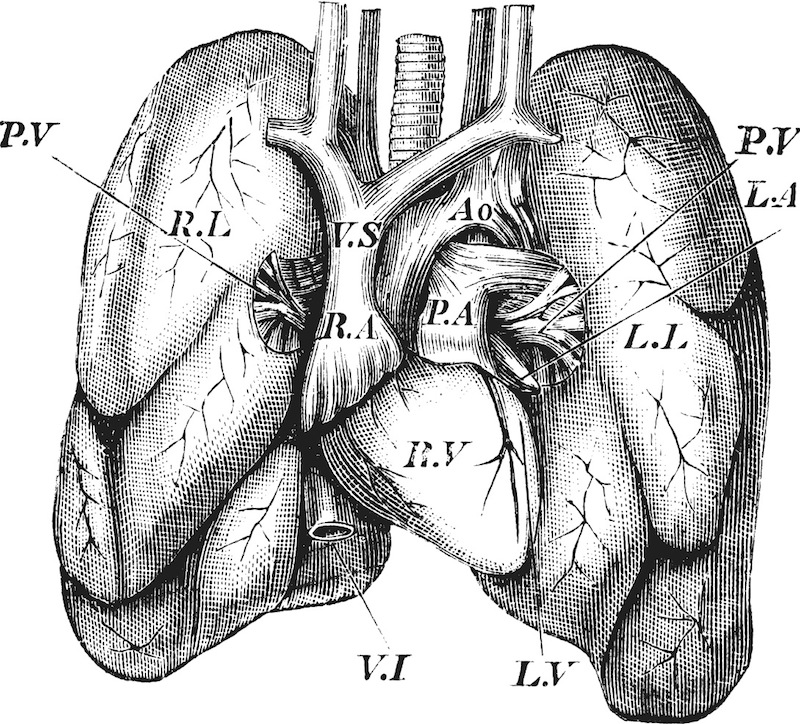

People have studied the circulatory system for thousands of years

The earliest known writings on the circulatory system appear in the Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical document dating to the 16th century B.C. The papyrus is believed to describe a physiological connection between the heart and the arteries, stating that after a person breathes air into the lungs, the air enters the heart and then flows into the arteries. (The work makes no mention of the role of red blood cells.)

Interestingly, the ancient Egyptians were cardiocentric — they believed the heart, rather than the brain, was the source of emotions, wisdom and memory, among other things. In fact, during the mummification process, Egyptians carefully removed and stored the heart and other organs, but ripped out the brain through the nose and discarded it.

Physicians followed an incorrect model of the circulatory system for 1500 years

In the 2nd century, the Greek physician and philosopher Galen of Pergamon came up with a believable model for the circulatory system. He rightly recognized that the system involves venous (dark red) and arterial (bright red) blood, and that the two types have different functions.

However, he also proposed that the circulatory system consists of two one-way systems of blood distribution (rather than a single, unified system), and that the liver produces venous blood that the body consumes. He also thought the heart was a sucking organ, rather than a pumping one.

Galen's theory reigned in Western medicine until the 1600s, when English physician William Henry correctly described blood circulation.

Red blood cells are special

Unlike most other cells in the body, red blood cells have no nuclei. Lacking this large internal structure, each red blood cell has more room to carry the oxygen the body needs. But without a nucleus, the cells cannot divide or synthesize new cellular components.

After circulating within the body for about 120 days, a red blood cell will die from aging or damage. But don't worry — your bone marrow constantly manufactures new red blood cells to replace those that perish.

The end of a relationship really can "break your heart"

A condition called stress cardiomyopathy entails a sudden, temporary weakening of the muscle of the heart (the myocardium). This results in symptoms akin to those of a heart attack, including chest pain, shortness of breath and arm aches.

The condition is also commonly known as "broken heart syndrome" because it can be caused by an emotionally stressful event, such as the death of a loved one or a divorce, breakup or physical separation from a loved one.

Self-experimentation led to circulatory breakthroughs

Cardiac catheterization is a common medical procedure used today and involves inserting a catheter (a long, thin tube) into a patient's blood vessel and threading it to the heart. Doctors can use the technique to perform a number of diagnostic tests on the heart, including measuring oxygen levels in different parts of the organ and checking the blood flow in the coronary arteries.

German physician Dr. Werner Forssmann invented the procedure in 1929 — when he performed it on himself.

He convinced a nurse to assist him, but she insisted that he conduct the procedure on her instead. He pretended to agree, and told her to lie on an operating table, where he secured her legs and hands. Then, without her knowledge, he anaesthetized his own left arm. He then pretended to prepare the nurse's arm for the procedure, until the drug took affect and he was able to insert the catheter into his arm.

Insertion complete (and nurse dismayed), the pair then walked to the X-ray room on the floor below, where Forssmann used a fluoroscope to help guide the catheter 60 centimeters (24 inches) into his heart.

Human blood comes in different colors — but not blue

The oxygen-rich blood that flows through your arteries and capillaries is bright red. After giving up its oxygen to your bodily tissues, your blood becomes dark red as it races back to your heart through your veins.

Although veins may sometimes look blue through your skin, it's not because your blood is blue. The deceptive color of your veins results from the way different wavelengths of light penetrate your skin, are absorbed and reflect back to your eyes — that is, only high-energy (blue) light can make it all the way to your veins and back.

- Related: How to improve your circulation

But that's not to say blood is never blue. The blood of most mollusks and some arthropods lacks the hemoglobin that gives human blood its redness, and instead contains the protein hemocyanin. This makes these animals' blood turn dark blue when oxygenated.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus