Dining In: How Cells Eat

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

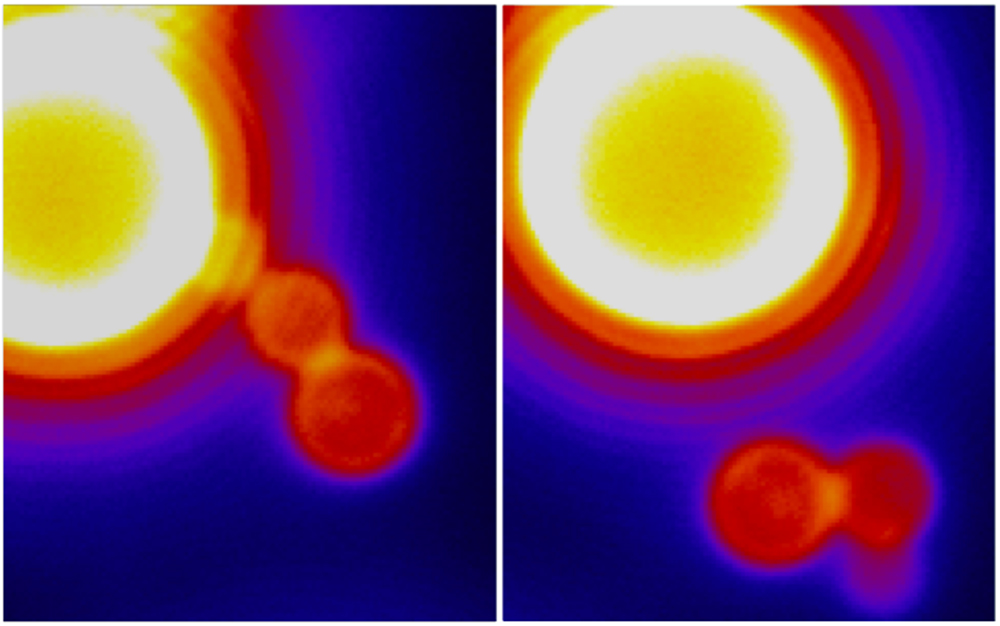

We need to eat and drink to survive, and so do our cells. Using a process called endocytosis, cells ingest nutrients, fluids, proteins and other molecules.

An international team of researchers recently revealed new details about endocytosis, an activity that, when it malfunctions, can lead to diseases such as muscular dystrophy, Alzheimer's and leukemia.

During endocytosis, the cell membrane curves inward, essentially forming a mouth to engulf ingestible cargo. Previously, scientists thought this mouth-forming, membrane-bending action required a large input of cellular energy. They also suspected it was driven by a pushing contest in the membrane between proteins called dynamin and oily molecules called lipids.

The research team, which included scientists at the National Institutes of Health and NIH-funded researchers at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, concluded that the process is much more relaxed: Dynamin and lipids work together, requiring only a modest input of energy, allowing a fine meal to slip down easily.

But it starts with some cellular choking. Where the membrane begins to curve, dynamin and lipid molecules are wedged together uncomfortably. The lipids, more flexible than the proteins, shift within the membrane to relieve overcrowding. As they do so, the membrane bends even more, forming a gaping maw around the meal. The process continues until the two membrane lips meet, fully engulfing the food.

Dynamin seals the mouth shut by encircling the region where the lips meet and tightening to form a pucker. Finally, cellular energy called GTP bites down, releasing the sustenance into the cell. Bon appétit!

Just as a good meal can be ruined by indigestion, endocytosis can be hijacked by parasites, bacteria and viruses that enter and infect human cells. As researchers learn more about endocytosis, they might be able to find ways to prevent this sort of infection.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research reported in this article was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health under its intramural program and grant R01GM42455.

This Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more:

Also in this series:

Cellular Garbage Disposals Clean Up

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus