Superbot: The Real Transformer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

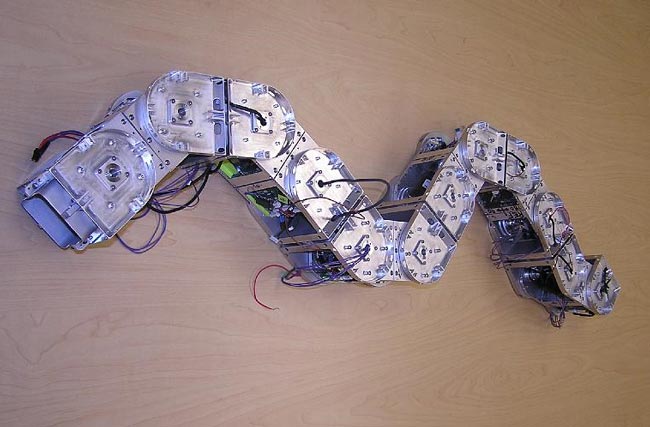

NASA wanted a robot that could start as 100 blocky modules dropped from an airplane to a desert, reconfigure into a rover that could drive to a sand dune, and then change again to "grow" legs and climb up it. Once the blocky robot reached the top, it would transform into a greenhouse that could protect a group of seeds for two weeks.

Only 20 of the modules were built during an ambitious project more than two years ago. But together, they are known as Superbot.

"You could build a lot of different robots where each does different things, but that would be too expensive," said Wei-Min Shen, director of the Polymorphic Robotics Laboratory at the University of Southern California.

Superbot cannot transform into trucks or F-22 fighter jets, like the gargantuan robots in the new "Transformers" movie. Yet researchers hope that modular robots similar to Superbot could one day decide when and where to shape-shift and adapt to their environments, depending on the job at hand.

Walk and roll

So far, Superbot has managed to form combinations with two, four or six legs, move like a robotic snake using a slithering or sidewinding motion, and even inch along like a caterpillar. Six of its modules can form a rolling track, and some combinations can even shimmy up ropes.

"If it needs to climb things, it can grow literally legs," Shen told LiveScience. "If it needs to go downhill, it can turn into a ball and simply roll."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such self-configuring robots have existed in the world of academic labs for some years now. Last year, a research group at the University of Pennsylvania caught attention with their walking modular robot that slowly reassembled itself after being kicked apart.

USC's Superbot can also demonstrate similar types of self-repair and self-assembly, because each module represents an independent robot that "talks" to other modules using infrared and radio communication. The modules constantly assess the situation see what other modules are nearby, and whether they should act as an arm or a leg for the combined Superbot.

"One of our demonstrations is that you can have a robot and cut it in half, so it becomes two independent snakes," Shen said. "There's no fixed central brain."

Four-legged Superbot may instantly become a pair of two-legged robots when cut in half. The two-legged robots sometimes use a "butterfly stroke" move similar to what swimmers use, Shen noted.

To build a 'living' robot

Several U.S. military branches and government agencies besides NASA have also shown interest in the idea of shape-shifting, self-repairing robots. Shen's work has received funding from the military's DARPA research branch, not to mention the U.S. Air Force, Army, and National Science Foundation.

However, a number of steps remain before Superbot can act as a fully autonomous being that makes decisions on its own. Creating artificial intelligence (AI) that can make higher-level decisions in traditional robots has already proved challenging, and modular robots have the added complexity of deciding what represents the best shape or size in any given environment.

"You have to tell the modules what shape to become," Shen noted. "The next step is let them decide, 'OK, I need three more legs.'"

One solution may involve looking to biology. Shen's lab has put forth the idea of "digital hormones" that would simulate the way in which hormones affect the mind and body. Some modules could flood certain signals to all the others, in order to communicate instructions such as whether to transform into a walking or rolling Superbot.

The biology analogy has come up before. Shen and his colleagues sometimes refer to Superbot's modules as "robotic stem cells," capable of morphing into a variety of roles.

Robots on the future frontier

A Superbot descendant might even achieve NASA's wildest dreams by forming a fully self-assembling space station, and help eliminate the need for expensive, time-consuming spacewalks conducted by human astronauts.

Shen and USC colleague Peter Will demonstrated such a concept on an air hockey table to simulate microgravity in space, with two robot modules that could use cable lines to grab other pieces, reel them in and dock.

Self-assembling space stations or Transformers may still be a long ways off, but Shen remains confident about building a better robot — or perhaps better robots that can build themselves.

"I have a strong belief in these things," Shen said. "Of course one person does not make much difference, but I do believe this is the future."

- Gallery - Cutting-Edge Robots

- Real Soldiers Love Their Robot Brethren

- Video - Future 'Bots

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus