PSA Test at Age 60 Predicts Risk of Death from Prostate Cancer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

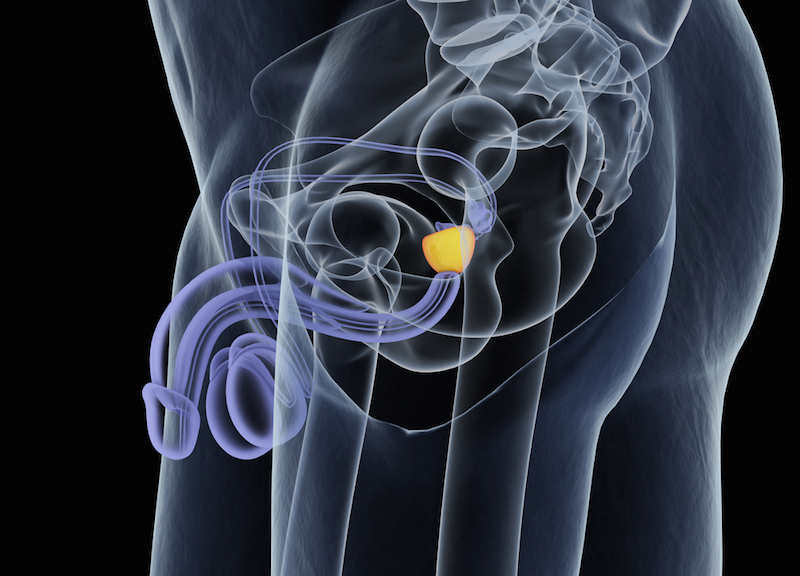

A single blood test at age 60 accurately predicts the risk of a man dying from prostate cancer in the next 25 years, a new study suggests.

The blood test, already widely used for prostate cancer screening, detects levels of a protein called prostate-specific antigen, or PSA.

Some health-care providers say routine screening using PSA tests could lead to overtreatment and overdiagnosis of slow-growing prostate cancers that may never affect a person during his lifetime.

A single PSA test done at age 60 has an advantage over regular screenings because the potential for overdiagnosis is lower. The age-60 test could predict who would need to come back for routine screening and who wouldn't, the researchers said.

"What we found ... was a new way of using an old test," study researchers Andrew Vickers and Dr. Hans Lilja, of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, said in a statement.

In the study, blood samples taken at age 60 from 1,167 men in Sweden were analyzed, and the men were tracked until they reached age 85 or died.

By the end of the analysis, 126 men had been diagnosed with prostate cancer, and 90 percent of those who had died from it had higher blood PSA levels than other men at age 60.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In general, doctors consider men who have a PSA level more than 4 nanograms per milliliter of blood to be at higher risk of developing prostate cancer. But some men with lower levels may still have cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute.

The men in the study who were diagnosed with prostate cancer had levels of 2 nanograms of PSA or higher per milliliter of blood when they were 60. Researchers concluded, then, that men of that age with similar PSA levels should undergo routine PSA tests from then on.

Men who had a PSA level of 1 nanogram of PSA or lower per milliliter of blood were considered at low risk of prostate cancer and had 0.2 percent chance of dying from prostate cancer and probably did not need regular screening, the researchers said. It's also possible that some of the men with low PSA levels did have prostate cancer, but the cancer did not shorten their lifespans, the study said.

However, PSA is not always a precise marker of prostate cancer. Non-dangerous conditions like prostate enlargement, inflammation and infection can also spike PSA levels. Unchangeable factors like age and race could also play a part, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Some doctors worry that overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer does more harm than good.

In fact, a new study by University of Florida researchers also published yesterday (Sept. 14) said that there is no evidence to support routine population screening for the cancer.

Treatment for a cancer that is likely to not even produce any symptoms or life-shortening effects could unnecessarily harm the patient, according to a 2007 article in the World Journal of Urology.

Evidence from patient trials does not support routine screening for prostate cancer for men with low PSA levels at age 60, according to the Florida researchers.

Their analysis was based on six previous trials, with 387,286 participants in total. They determined that while routine population screening increased the odds of early detection, it did not have a big enough effect on mortality among those men.

Scientists do not recommend doctors actively invite men for routine prostate cancer screenings, and said men should be informed of the risks for overdiagnosis involved with the screenings, the study said.

Both studies were published online in the British Medical Journal.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus