Scientists Can See Brain Blunders Coming

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About a second before mistakes are made, brain wave patterns predict the looming blunder, a new study finds.

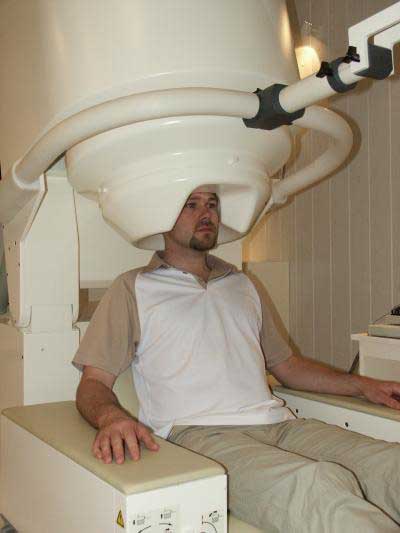

Researchers hooked 14 volunteers up to a non-invasive brain-wave recording machine that employs magnetoencephalography (MEG). Then they administered really boring tests sure to trigger mistakes.

During a half-hour test sitting at a computer, a random number from 1 to 9 flashes onto the screen every two seconds. The object is to tap a button as soon as any number except 5 appears.

The test is so monotonous that even when a 5 showed up, the subjects spontaneously hit the button an average of 40 percent of the time, explained study leader Ali Mazaheri at the University of California, Davis.

By analyzing the recorded MEG data, the research team found that about a second before these errors were committed, brain waves in two regions were stronger than when the subjects correctly refrained from hitting the button. In the back of the head (the occipital region), alpha wave activity was about 25 percent stronger, and in the middle region, the sensorimotor cortex, there was a corresponding increase in the brain's mu wave activity.

"The alpha and mu rhythms are what happen when the brain runs on idle," Mazaheri explained in a statement. "Say you're sitting in a room and you close your eyes. That causes a huge alpha rhythm to rev up in the back of your head. But the second you open your eyes, it drops dramatically, because now you're looking at things and your neurons have visual input to process."

The work is part of a broad effort to read the mind.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In separate research last year, scientists found that some mistakes can be predicted by changes in brain blood flow 30 seconds before an error. A study earlier this month showed that brain scans can read memories with surprising accuracy. Researchers at Tufts University, meanwhile, are developing ways for a computer to tell if you are overworked, under-worked or not working at all.

The team also found that errors triggered immediate changes in wave activity in the front region of the brain, which appeared to drive down alpha activity in the rear region, "It looks as if the brain is saying, 'Pay attention!' and then reducing the likelihood of another mistake," Mazaheri said.

It shouldn't take too many years to incorporate these findings into practical applications, Mazaheri said. For example, a wireless EEG could be deployed at an air traffic controller's station to trigger an alert when it senses that alpha activity is beginning to regularly exceed a certain level.

It could also provide new therapies for children with ADHD, he said. "Instead of watching behavior — which is an imprecise measure of attention — we can monitor these alpha waves, which tell us that attention is waning. And that can help us design therapies as well as evaluate the efficacy of various treatments, whether it's training or drugs."

The research is published online today by the journal Human Brain Mapping. The work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and BrainGain Smart Mix Program of the Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs.

- World Trivia: Challenge Your Brain

- Mind-Reading Hat Could Prevent Brain Farts

- Why We Learn From Mistakes

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus