5 Moon Mysteries to Ponder During Saturday's Supermoon

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Considering how much scientists know about inaccessible realms of the universe, from the interiors of black holes to the nuclei of atoms, you'd think they would have our nearest celestial neighbor all figured out. Not so. The moon still harbors secrets aplenty.

The following five moon mysteries have had astronomers scratching their heads for decades, centuries and in some cases even thousands of years. So, on Saturday (May 5) while you're gazing at the "supermoon" — the term for when the full moon coincides with lunar perigee, making it loom especially large and bright in the night sky — give your head a scratch, too, and ponder these intriguing lunar secrets. [View with images]

Where did it come from?

Cultures worldwide have long offered up myths to explain the moon's existence. Nowadays, scientists have other ideas of what really happened.

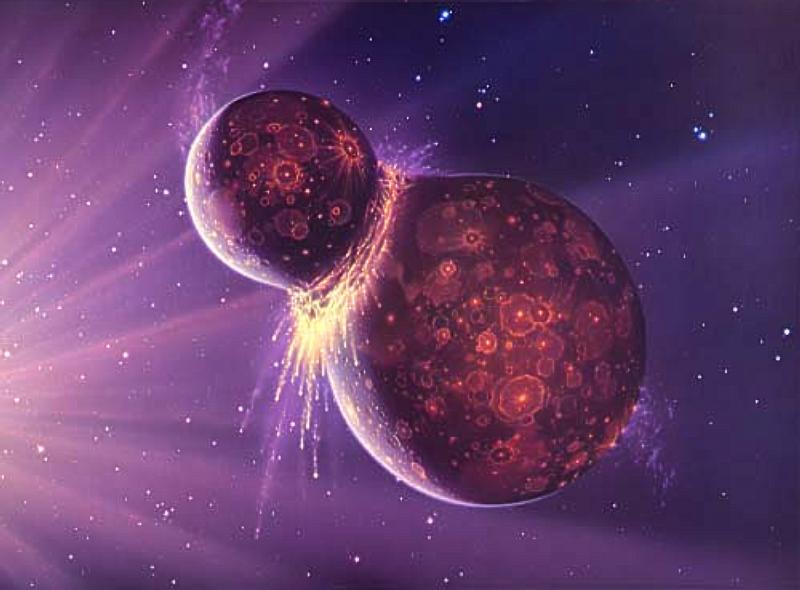

Many lines of evidence (including the moon's smallish core, its complement of certain elements and computer simulations rewinding the Earth-moon orbital dance over eons) point to the moon being spawned in a giant impact. According to this theory, about 4.5 billion years ago, a Mars-size body slammed into a young, molten Earth, and that collision gouged out the material that would coalesce into our lunar neighbor.

This picture has problems, however. The theoretical impactor, dubbed Theia, should have left residue with distinctive characteristics, but they have not been detected. And the amount of certain substances in the moon — too much frozen water, for example — does not readily mesh with a hot, cataclysmic origin scenario.

Why two-faced?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The moon is "tidally locked" to Earth, meaning only one hemisphere faces us. We know that side well, with its dark regions called maria, or "seas," of cooled magma. Oddly, however, these maria are virtually absent from the back side of the moon, as has been revealed to us by probes (and seen in person by Apollo 8 astronauts). The proverbial "dark side of the moon" also is much more pockmarked by craters.

The starkly different hemispheres have been partly explained by the far side having a crust roughly 9 miles (15 kilometers) thicker than that of the near side. The crust on the side facing us could have more easily cracked under the onslaught of meteorites, causing maria-forming magma to be released from deeper in the moon. But that crustal asymmetry is an enigma itself.

The extra cratering, meanwhile, could stem from greater exposure to space on the far side than on the Earth-shielded near side. Better modeling of the moon's interior and a better understanding of the damage wrought by impacting bodies might help explain this strange two-facedness. [What Does the Top of the Moon Look Like?]

Why so big near the horizon?

The moon stays the same size throughout the night, regardless of whether it's hovering near the horizon or soaring overhead. However, a low-hanging moon appears much larger than a high-flying one. This trick of the brain — known either as the moon illusion or the Ponzo illusion — has been observed since ancient times, but still has no generally accepted explanation.

One theory holds that we're used to seeing clouds just a few miles above us, while we know that clouds on the horizon can be many miles distant. If a cloud on the horizon is the same size as clouds normally are overhead despite its great distance, we know it must be huge. And because the moon near the horizon is the same size as it normally is overhead, our brains automatically tack on a similar size increase.

But not everyone thinks clouds have worked their magic on our brains to such a great extent. One alternative hypothesis holds that the moon seems larger near the horizon because we can compare its size to nearby trees and other objects on Earth — and it looms large in comparison. Overhead, amid the vast expanse of outer space, the moon seems diminutive. Either way, the illusion will work wonders on Saturday's supermoon. "On May 5th, this 'Moon illusion' will amplify a full Moon that's extra-big to begin with," NASA stated in a press release. "The swollen orb rising in the east at sunset will seem super indeed."

Why so blue?

The moon is much more watery than would be expected. Water ice has turned up meters-deep in craters near the poles, particularly in a plume kicked up by the deliberate impact of NASA's LCROSS probe in 2009. Studies have suggested the interior of the moon is also far wetter than ever supposed (though still hyper-arid compared with modern-day Earth). Recent re-examinations of the rock samples brought back to Earth by astronauts have even yielded signs of water.

Icy comets most likely delivered a substantial portion of this water when they smashed into the moon, but scientists are still at a loss about the sheer quantity of H2O. It's possible, they believe, that some of the water may even be made right there on the moon, by protons in the solar wind interacting with metal oxides in the moon rocks. [Where Did Earth's Water Come From?]

Is it alone?

Astronomers think Earth might actually have two moons. One is that waxing and waning nightlight we all know and love, while the other is a tiny asteroid, no bigger than a smart car, making huge donuts around Earth for a while before zipping off into the distance. Based on the number and distribution of asteroids in the solar system, researchers estimate that there should be at least one space rock at least 1 meter (3.3 feet) wide orbiting Earth at any given time. They're not always the same rock, but rather an ever-changing cast of "temporary moons."

In the scientists' theoretical model, our planet's gravity captures these asteroids as they pass near us on their way around the sun. When one is drawn in, it typically makes three irregularly shaped swings around Earth — sticking with us for about nine months — before hurtling on its way.

But the temporarily captured asteroids are tough to spot — too small when they're orbiting far away, and too fast and blurry when they swing close by — so we can't be sure they're there. If future sky surveys prove we really do have a second moon, then many scientists think we should build a spacecraft to go get it and bring it back to Earth.

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus